Volcanic Lakeshore Cliff

Overview

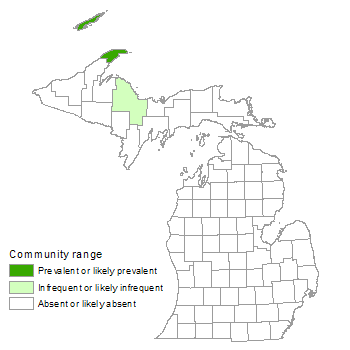

Volcanic lakeshore cliffs consist of vertical or near-vertical exposures of bedrock, which support less than 25% vascular plant coverage, although lichens, mosses, and liverworts are abundant on some rock surfaces. The cliffs range in height from 3 to 80 meters (10 to 260 ft) and occur on Lake Superior along the Keweenaw Bay shoreline of the Keweenaw Peninsula and along the northern shoreline of Isle Royale. Volcanic lakeshore cliffs are characterized by high site moisture due to the proximity to Lake Superior and a stressed and unstable environment because of severe waves, wind, and winter ice.

Rank

Global Rank: GU - Unrankable

State Rank: S1 - Critically imperiled

Landscape Context

The bedrock of the Keweenaw Peninsula dips steeply toward the north and into Lake Superior, while the south face of the bedrock forms cliffs. In most places, the cliffs are only a few meters high, but near Bete Grise the cliffs are nearly 80 m (260 ft) high. Cliffs occur along large stretches of the 32 km (20 mile)-long southern shoreline of the Keweenaw Peninsula and Manitou Island between Bete Grise to the Manitou Island lighthouse at the east end of the island. Volcanic rock cliffs similarly form the north shoreline of Isle Royale. On the Keweenaw Peninsula, most of the cliffs are formed of massive basalt, but there are also some areas of cliff composed of volcanic conglomerate rock. Volcanic lakeshore cliff also occurs on the shorelines of Lake Superior in Ontario and Minnesota. In Michigan, volcanic lakeshore cliff is typically bordered by boreal forest and occasionally by dry-mesic northern forest, mesic northern forest, or volcanic bedrock glade. Along the shoreline, volcanic lakeshore cliffs are interspersed with areas of volcanic bedrock lakeshore, volcanic cobble shore, and sand and gravel beach.

Soils

There is little soil development on the steep rock face of the cliffs. Some organic soil development occurs in crevices in the rock face and on the upper lip of the cliffs.

Natural Processes

The cliffs are exposed to almost continual wave action from Lake Superior. During winter, ice adds to the erosive environment along the shore, both for the cliff and the upland forest along the cliff edge. Storm winds off Lake Superior uproot trees and erode soils. Windblown trees at the base of the cliff provide localized areas for soil accumulation. Thin soils, winter winds, full exposure, and summer droughts produce a desiccating environment for plants. The regularly occurring fog along the coast serves to somewhat mitigate these desiccating effects during the growing season.

Vegetation

While mosses and lichens are common on the exposed cliff face, vascular plant cover is sparse, being generally restricted to the flat, exposed bedrock at the upper edge of the cliff (i.e., lip), cracks and joints in the cliff face, and along the cliff base if a ledge of talus, cobble, sand, or bedrock is present between the cliff and the open water. The upper edge of the cliff is typically backed by boreal forest, with abundant windthrown trees resulting from strong lake winds. Herbaceous species characteristic of the upper flat edge or lip include downy oatgrass (Trisetum spicatum, state special concern), harebell (Campanula rotundifolia), upland white goldenrod (Solidago ptarmicoides), Gillman’s goldenrod (S. simplex), balsam ragwort (Packera paupercula), wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana), yarrow (Achillea millefolium), hair grass (Deschampsia cespitosa), and the invasive species Canada bluegrass (Poa compressa). Shrubs occurring along the upper lip include mountain alder (Alnus viridis), soapberry (Shepherdia canadensis), serviceberries (Amelanchier spp.), and wild rose (Rosa acicularis). Some of the few plants that occur on the cliff face are occasional patches of common polypody (Polypodium virginianum), harebell, and hair grass. Dense, shrubby stands of white spruce (Picea glauca), northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis), paper birch (Betula papyrifera), mountain ash (Sorbus decora), and balsam fir (Abies balsamea) form the coastal boreal forest along the edge of the cliff.

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Graminoids

- poverty grass (Danthonia spicata)

- tufted hair grass (Deschampsia cespitosa)

- downy oat-grass (Trisetum spicatum)

Forbs

- yarrow (Achillea millefolium)

- harebell (Campanula rotundifolia)

- wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana)

- balsam ragwort (Packera paupercula)

- three-toothed cinquefoil (Sibbaldiopsis tridentata )

- upland white goldenrod (Solidago ptarmicoides)

- Gillman’s goldenrod (Solidago simplex)

Ferns

- common polypody (Polypodium virginianum)

Shrubs

- mountain alder (Alnus viridis)

- serviceberries (Amelanchier spp.)

- wild rose (Rosa acicularis)

- soapberry (Shepherdia canadensis)

Trees

- balsam fir (Abies balsamea)

- serviceberries (Amelanchier spp.)

- paper birch (Betula papyrifera)

- white spruce (Picea glauca)

- white pine (Pinus strobus)

- mountain-ash (Sorbus decora)

- northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis)

Noteworthy Animals

Cliffs provide nesting habitat for raptors and the common ravens (Corvus corax).

Rare Plants

- Castilleja septentrionalis (pale Indian paintbrush, state threatened)

- Polygonum viviparum (alpine bistort, state threatened)

- Trisetum spicatum (downy oatgrass, state special concern)

Rare Animals

- Falco columbarius (merlin, state threatened)

- Falco peregrinus (peregrine falcon, state endangered)

- Haliaeetus leucocephalus (bald eagle, state threatened)

Biodiversity Management Considerations

Threats to lakeshore cliffs include shoreline development, logging of adjacent uplands and associated soil erosion, excessive foot traffic along the upper edge, and invasive plants. The thin soils and unstable environment make soil development and plant reestablishment slow, highlighting the importance of minimizing logging and excessive trampling along the upper edge of cliffs. Maintaining a mature, unfragmented forested buffer around volcanic lakeshore cliff may help limit the local seed source for invasive species distributed by wind or birds. Some of the invasive plants that may threaten the diversity and structure of volcanic lakeshore cliffs include spotted knapweed (Centaurea stoebe), ox-eye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare), Canada bluegrass, Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis), sheep sorrel (Rumex acetosella), and hawkweeds (Hieracium spp.). Monitoring and control efforts to detect and remove these and other invasive species will help maintain the ecological integrity of limestone lakeshore cliff and surrounding natural communities.

Variation

Volcanic lakeshore cliffs occur on both volcanic conglomerate and massive basalt. Vegetation diversity appears to be higher on the conglomerate substrate.

Similar Natural Communities

Granite lakeshore cliff, sandstone lakeshore cliff, limestone lakeshore cliff, granite cliff, limestone cliff, sandstone cliff, volcanic cliff, volcanic bedrock glade, granite bedrock glade, volcanic bedrock lakeshore, and northern bald.

Places to Visit

- Bare Bluffs Cliffs, Michigan Nature Association (Grinnell Memorial Sanctuary at Bare Bluff), Keweenaw Co.

- Bete Grise, Michigan Nature Association (Grinnell Memorial Sanctuary at Bare Bluff), Keweenaw Co.

- Isle Royale National Park, Keweenaw Co.

- Manitou Island, Baraga State Forest Management Unit, Keweenaw Co.

Relevant Literature

- Albert, D.A., P. Comer, D. Cuthrell, D. Hyde, W. MacKinnon, M. Penskar, and M. Rabe. 1997. The Great Lakes bedrock lakeshores of Michigan. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 218 pp.

- Bornhorst, T.J., and W.I. Rose. 1994. Self-guided geological field trip to the Keweenaw Peninsula, Michigan. Proceedings of the Institute on Lake Superior Geology. Volume 40, Part 2. 185 pp.

- Dorr, J.A., Jr., and D.F. Eschman. 1970. Geology of Michigan. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI. 470 pp.

- Faber-Langendoen, D., ed. 2001. Plant communities of the Midwest: Classification in an ecological context. Association for Biodiversity Information, Arlington, VA. 61 pp. + appendix (705 pp.).

- Given, D.R., and J.H. Soper. 1981. The arctic-alpine element of the vascular flora at Lake Superior. National Museums of Canada, Publication in Botany 10: 1-70.

- LaBerge, G.L. 1994. Geology of the Lake Superior region. Geoscience Press, Phoenix, AZ. 313 pp.

- Reed, R.C., and J. Daniels. 1987. Bedrock geology of northern Michigan. State of Michigan Department of Natural Resources. Map: 1: 500,000.

- Reschke, C. 1985. Vegetation of the conglomerate rock shoreline of the Keweenaw Peninsula, northern Michigan. M.S. thesis. University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI. 118 pp.

- Slavick, A.D., and R.A. Janke. 1987. The vascular flora of Isle Royale National Park. Michigan Botanist 26: 91-134.

- Thompson, P.W., and J.R. Wells. 1974. Vegetation of Manitou Island, Keweenaw County, Michigan. Michigan Academician 6: 307-312.

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: March 7, 2026).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.