Volcanic Bedrock Lakeshore

Overview

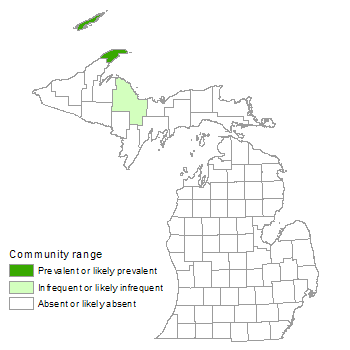

Volcanic bedrock lakeshore is a sparsely vegetated community dominated by mosses and lichens, with a scattered coverage of vascular plants. The community is located primarily along the Lake Superior shoreline on the Keweenaw Peninsula and Isle Royale. This Great Lakes coastal plant community includes all types of volcanic bedrock, including basalt, conglomerate composed of volcanic rock, and rhyolite.

Rank

Global Rank: G4G5 - Rank is uncertain, ranging from apparently secure to secure

State Rank: S2 - Imperiled

Landscape Context

Bedrock of the Keweenaw Peninsula and Isle Royale was deposited from 1,100 to 1,000 million years ago, during the Late Precambrian, a period of extensive surface volcanic activity. Rather than forming volcanic cones, the basaltic lavas flowed out through long fissures, covering the landscape with thick deposits of lava, called flood basalt. The huge mass of Keweenawan rock, up to 25 km (15.5 miles) thick, eventually sagged to form a structural basin, now occupied by Lake Superior. The sagging caused the volcanic rock of the Keweenaw Peninsula to tilt steeply downward to the north, toward the center of the Lake Superior basin, while the volcanic rock of Isle Royale’s south shoreline tilted steeply south, also facing the center of Lake Superior. In contrast, the south shore of the Keweenaw Peninsula and the north shore of Isle Royale form steep cliffs. Volcanic rhyolite, an angular, reddish rock found locally on the south shore of the Keweenaw Peninsula east of Bete Grise, has a depauperate flora similar to that of massive basalt. This community also occurs along the Lake Superior shoreline in Ontario and Minnesota.

Volcanic bedrock lakeshore is typically bordered by boreal forest along its upland margin and occasionally by dry-mesic northern forest, mesic northern forest, or volcanic bedrock glade. Where streams flow through the community, occasionally northern shrub thicket may border its inland edge. Along the shoreline, the volcanic bedrock lakeshore is interspersed with areas of volcanic lakeshore cliff, volcanic cobble shore, and sand and gravel beach.

Soils

Almost no soil development takes place on either the massive, fine-grained basalts or the volcanic conglomerates. The only places where plants are able to establish are in cracks, joints, vesicles, and depressions in the bedrock, where small amounts of organic matter accumulate. Cracks, joints, and depressions are much more abundant on the volcanic conglomerate, but still provide relatively few places for soil development. Freshly broken rock surfaces are mildly alkaline in pH.

Natural Processes

Extreme conditions characterize all parts of this plant community. Near the water’s edge, storm waves regularly scour the rock. During the winter, ice scours and abrades the rock even more violently. Freezing rain and mist coat both the rock and vegetation, and in combination with high winds, result in dwarf shrubs and stunted trees along the shore. Fog occurs on an almost daily basis, allowing plants more characteristic of cooler northern or high elevation habitats to survive beyond their normal range. Lightning strikes result in occasional tree mortality and fires. Wind storms maintain the open forest structure, causing blowdown of shallowly rooted trees. Fire and windthrow are both confined to the upland margin of volcanic bedrock lakeshore.

Vegetation

The plants covering the greatest percentage of the lakeshores are mosses and lichens, with only scattered coverage of vascular plants. Mosses and lichens are able to establish and survive close to the lake, while vascular plants are generally above the zone of active storm waves and ice scour. Herbaceous species, listed in order of common occurrence, include harebell (Campanula rotundifolia), wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana), three-toothed cinquefoil (Sibbaldiopsis tridentata), downy oatgrass (Trisetum spicatum, state special concern), yarrow (Achillea millefolium), hair grass (Deschampsia cespitosa), butterwort (Pinguicula vulgaris, state special concern), tufted bulrush (Trichophorum cespitosum), fescue (Festuca saximontana), dwarf Canadian primrose (Primula mistassinica), and the invasive plant Canada bluegrass (Poa compressa). Other common species include balsam ragwort (Packera paupercula), grass-leaved goldenrod (Euthamia graminifolia), Gillman’s goldenrod (Solidago simplex), fireweed (Chamerion angustifolium), northern bog violet (Viola nephrophylla), poverty grass (Danthonia spicata), and wormwood (Artemisia campestris). Prevalent shrubs include low sweet blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium), bog-bilberry (V. uliginosum, state threatened), bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi), common juniper (Juniperus communis), creeping juniper (J. horizontalis), dwarf raspberry (Rubus pubescens), ninebark (Physocarpus opulifolius), serviceberries (Amelanchier spp.), soapberry (Shepherdia canadensis), and bush honeysuckle (Diervilla lonicera). Stunted, shrub-sized trees included balsam fir (Abies balsamea), northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis), quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides), white pine (Pinus strobus), and white spruce (Picea glauca). Perched meadows at the edges of seasonal rock pools are dominated by bluejoint grass (Calamagrostis canadensis), hair grass, downy oatgrass, poverty grass, tufted bulrush, and sedges (Carex buxbaumii and C. castanea).

Several vegetation zones are often apparent. Wave action and ice scour are strongest near the lakeshore, producing a “wave-washed zone,” that is almost devoid of vegetation except for scattered tufts of mosses and lichen. With greater distance above the lake, plant cover increases, with lichens predominating. On the high, dry rocks, a diversity of lichens forms a nearly continuous cover, while mosses, liverworts, herbs, and woody plants are also well represented. Herbs and woody plants are largely restricted to narrow cracks and joints in the rock, where there is limited soil development and greater moisture retention. Narrow, perched meadows of tufted grasses and sedges are found along the edges of seasonal rock pools.

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Graminoids

- blue-joint (Calamagrostis canadensis)

- sedges (Carex buxbaumii, C. castanea, C. cryptolepis, and C. rossii)

- poverty grass (Danthonia spicata)

- tufted hair grass (Deschampsia cespitosa)

- blue wild-rye (Elymus glaucus)

- Rocky Mountain fescue (Festuca saximontana)

- tufted bulrush (Trichophorum cespitosum)

- downy oat-grass (Trisetum spicatum)

Forbs

- yarrow (Achillea millefolium)

- wormwood (Artemisia campestris)

- harebell (Campanula rotundifolia)

- pale Indian paintbrush (Castilleja septentrionalis)

- fireweed (Chamerion angustifolium)

- prairie cinquefoil (Drymocallis arguta)

- large-leaved aster (Eurybia macrophylla)

- grass-leaved goldenrod (Euthamia graminifolia)

- wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana)

- balsam ragwort (Packera paupercula)

- butterwort (Pinguicula vulgaris)

- bird’s-eye primrose (Primula mistassinica)

- pearlwort (Sagina nodosa)

- three-toothed cinquefoil (Sibbaldiopsis tridentata)

- upland white goldenrod (Solidago ptarmicoides)

- Gillman’s goldenrod (Solidago simplex)

- sand violet (Viola adunca)

- northern bog violet (Viola nephrophylla)

Fern Allies

- common horsetail (Equisetum arvense)

Lichens

- map lichens (Rhizocarpon spp.)

- orange wall lichen (Xanthoria spp.)

Mosses

- pseudoleskea mosses (Pseudoleskea spp.)

- schistidium mosses (Schistidium spp.)

- tortured tortella moss (Tortella tortuosa)

Shrubs

- mountain alder (Alnus viridis)

- serviceberries (Amelanchier spp.)

- bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi)

- black hawthorn (Crataegus douglasii)

- bush honeysuckle (Diervilla lonicera)

- common juniper (Juniperus communis)

- creeping juniper (Juniperus horizontalis)

- sweet gale (Myrica gale)

- ninebark (Physocarpus opulifolius)

- wild rose (Rosa acicularis)

- dwarf raspberry (Rubus pubescens)

- soapberry (Shepherdia canadensis)

- low sweet blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium)

- alpine blueberry (Vaccinium uliginosum)

Trees

- balsam fir (Abies balsamea)

- juneberry (Amelanchier arborea)

- paper birch (Betula papyrifera)

- white spruce (Picea glauca)

- white pine (Pinus strobus)

- quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides)

- northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis)

Noteworthy Animals

Surveys of volcanic bedrock lakeshore documented twenty species of land snails, including two rare species with relict periglacial and arctic affinities, Vertigo cristata and Vertigo paradoxa.

Two groups of rare species are represented on the volcanic bedrock lakeshore, arctic-alpine species characteristic of more northerly open environments and disjunct species from the mountains of the west and Pacific Northwest. Cool, moist, and foggy conditions prevail along the shores of Lake Superior’s Keweenaw Peninsula and Isle Royale, accounting for the affinity of the plant communities of the shoreline to those of more northern latitudes. The rocky coastal habitat along Lake Superior also shares bedrock conditions with the Pacific Northwest.

Rare Plants

- Allium schoenoprasum var. sibiricum (wild chives, state threatened)

- Braya humilis (low northern rock cress, state threatened)

- Calamagrostis lacustris (northern reedgrass, state threatened)

- Calamagrostis stricta (narrow-leaved reedgrass, state threatened)

- Calypso bulbosa (calypso, state threatened)

- Carex media (sedge, state threatened)

- Carex rossii (Ross’s sedge, state threatened)

- Carex scirpoides (bulrush sedge, state threatened)

- Castilleja septentrionalis (pale Indian paintbrush, state threatened)

- Crataegus douglasii (Douglas’s hawthorn, state special concern)

- Cypripedium arietinum (ram’s head lady’s-slipper, state special concern)

- Danthonia intermedia (wild oatgrass, state special concern)

- Draba arabisans (rock whitlow-grass, state special concern)

- Elymus glaucus (blue wild-rye, state special concern)

- Empetrum nigrum (black crowberry, state threatened)

- Luzula parviflora (small-flowered wood rush, state threatened)

- Phacelia franklinii (Franklin’s phacelia, state threatened)

- Phleum alpinum (mountain timothy, presumed extirpated from Michigan)

- Pinguicula vulgaris (butterwort, state special concern)

- Poa alpina (alpine bluegrass, state threatened)

- Polygonum viviparum (alpine bistort, state threatened)

- Potentilla pensylvanica (prairie cinquefoil, state threatened)

- Sagina nodosa (pearlwort, state threatened)

- Senecio indecorus (rayless mountain ragwort, state threatened)

- Trisetum spicatum (downy oatgrass, state special concern)

- Vaccinium cespitosum (dwarf bilberry, state threatened)

- Vaccinium uliginosum (bog bilberry, state threatened)

- Viburnum edule (squashberry, state threatened)

Rare Animals

- Falco peregrinus (Peregrine falcon, state endangered)

- Haliaeetus leucocephalus (bald eagle, state threatened)

- Vertigo cristata (land snail, state special concern)

- Vertigo paradoxa (land snail, state special concern)

Biodiversity Management Considerations

Lichens and mosses are especially sensitive to off-road vehicle and foot traffic. In many stretches of the shoreline this damage is minimal because of the extreme steepness of the shores. While herbaceous vegetation is also vulnerable to foot traffic, roots are often protected within cracks in the rock. Soil recovery and plant reestablishment are slow in this harsh environment. Invasive species that threaten the diversity and community structure of volcanic bedrock lakeshore include spotted knapweed (Centaurea stoebe), ox-eye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare), Canada bluegrass, Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis), hawkweeds (Hieracium spp.), common St. John’s-wort (Hypericum perforatum), sheep sorrel (Rumex acetosella), garden tansy (Tanacetum vulgare), and common mullein (Verbascum thapsus). Maintaining a mature, unfragmented forested buffer around volcanic bedrock lakeshores may help limit the local seed source for invasive species distributed by wind or birds. Monitoring and control efforts to detect and remove these and other invasive species will help maintain the ecological integrity of volcanic bedrock lakeshore and surrounding natural communities.

Variation

In earlier versions of the community classification, the volcanic conglomerates had been considered a separate vegetation type due to the higher plant species richness and greater vegetative cover on the conglomerates of the Keweenaw Peninsula. However, because the basaltic bedrock of Manitou Island at the east end of the Keweenaw Peninsula and on Isle Royale supports a similar and equally diverse vascular flora as the conglomerate of the Keweenaw Peninsula, all of the volcanic bedrock lakeshore types have been combined into one type, volcanic bedrock lakeshore.

The basalt bedrock lakeshores of the Keweenaw Peninsula are characterized by lower plant richness and cover than the basalt bedrock lakeshores of Isle Royale, probably due to the lack of plant habitat in the form of cracks and small cavities in the smooth, fine-grained basaltic rock. In contrast, the volcanic conglomerates of the Keweenaw Peninsula support many more plant species and higher coverage values than the basalt. Rhyolite bedrock is also low in plant diversity and coverage compared to volcanic conglomerate bedrock.

Similar Natural Communities

Granite bedrock lakeshore, sandstone bedrock lakeshore, limestone bedrock lakeshore, volcanic cobble shore, volcanic bedrock glade, volcanic lakeshore cliff, and granite bedrock glade.

Places to Visit

- Bete Grise, Bear Bluff, and Big Bay West, Baraga State Forest Management Unit, Keweenaw Co.

- Copper Harbor Lighthouse and Porters Island, Fort Wilkins State Historic Park, Keweenaw Co.

- Horseshoe Harbor, The Nature Conservancy (Mary Macdonald Preserve at Horseshoe Harbor), Keweenaw Co.

- Isle Royale National Park, Keweenaw Co.

- Keweenaw Point, High Rock, and Keystone Bay, Baraga State Forest Management Unit, Keweenaw Co.

- Porcupine Shore, Porcupine Mountains Wilderness State Park, Ontonagon Co.

Relevant Literature

- Albert, D.A., P. Comer, D. Cuthrell, D. Hyde, W. MacKinnon, M. Penskar, and M. Rabe. 1997. The Great Lakes bedrock lakeshores of Michigan. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 218 pp.

- Bornhorst, T.J., and W.I. Rose. 1994. Self-guided geological field trip to the Keweenaw Peninsula, Michigan. Proceedings of the Institute on Lake Superior Geology. Volume 40, Part 2. 185 pp.

- Dorr, J.A., Jr., and D.F. Eschman. 1970. Geology of Michigan. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI. 470 pp.

- Faber-Langendoen, D., ed. 2001. Plant communities of the Midwest: Classification in an ecological context. Association for Biodiversity Information, Arlington, VA. 61 pp. + appendix (705 pp.).

- Given, D.R., and J.H. Soper. 1981. The arctic-alpine element of the vascular flora at Lake Superior. National Museums of Canada, Publication in Botany 10: 1-70.

- LaBerge, G.L. 1994. Geology of the Lake Superior region. Geoscience Press, Phoenix, AZ. 313 pp.

- Reschke, C. 1985. Vegetation of the conglomerate rock shoreline of the Keweenaw Peninsula, northern Michigan. M.S. thesis. University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI. 118 pp.

- Slavick, A.D., and R.A. Janke. 1987. The vascular flora of Isle Royale National Park. Michigan Botanist 26: 91-134.

- Thompson, P.W., and J.R. Wells. 1974. Vegetation of Manitou Island, Keweenaw County, Michigan. Michigan Academician 6: 307-312.

For a full list of references used to create this description, please refer to the natural community abstract for Volcanic Bedrock Lakeshore.

More Information

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: March 5, 2026).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.