Granite Bedrock Glade

Overview

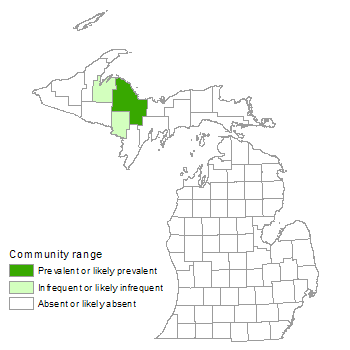

Granite bedrock glade consists of an open forested or savanna community found where knobs of granitic bedrock types are exposed at the surface. The sparse vegetation consists of scattered open-grown trees, scattered shrubs or shrub thickets, and a partial turf of herbs, grasses, sedges, mosses, and lichens. Granite bedrock glades typically occupy areas of steep to stair-stepped slopes, with short cliffs, and exposed knobs of bedrock. The community occurs in the western Upper Peninsula with primary concentrations in Marquette, Baraga, and Dickinson Counties.

Rank

Global Rank: G3G5

State Rank: S2 - Imperiled

Landscape Context

A broad range of igneous and metamorphic rocks, including gneiss, schist, granite, and quartzite, are often loosely referred to as “granitic” or “granite.” Granite bedrock glade occurs on granite, schist, gabbro, gneiss, slate, “iron formations,” greenstones, and a diversity of other resistant igneous and metamorphic rock types of the Michigamme Highlands that formed during the Precambrian Era, approximately 600 to 3,500 million years ago. These rock types form large rounded ridges that were shaped and polished by the continental ice sheets about 10,000 years ago.

The community occurs both inland and adjacent to the Lake Superior shoreline. Granitic bedrock glades typically occupy areas of steep to stair-stepped slopes, with short cliffs, exposed bedrock knobs, and talus slopes occurring at the base of the bedrock exposures. The forest types surrounding granitic bedrock are typically dry-mesic northern forest or mesic northern forest. Along the Lake Superior shoreline, boreal forest is a common associate and in localized areas, granite bedrock glade can occur adjacent to granite bedrock lakeshore, granite lakeshore cliff, volcanic cobble shore, and sand and gravel beach.

Soils

Soil development is generally restricted to cracks and depressions within the rock, where plant debris and sand and gravel resulting from mechanical and biological weathering of the bedrock can accumulate. These soils are typically very shallow and low in nutrients. Thin soils are typically 1 to 4 cm (0.4 to 1.6 in) deep, strongly acidic, and characterized by low moisture availability. Exfoliation of rock slabs and frost wedging is characteristic of granite and contributes to soil formation. Numerous large boulders, slabs, and small granitic rocks occur scattered throughout the glades, and talus slopes occur at the base of many bedrock exposures.

Natural Processes

Windthrow, desiccation, fire, and exfoliation of rock slabs are all important natural processes for bedrock glade communities. Windthrown trees are common as a result of thin soils and strong winds associated with Lake Superior. Thin soils, cold winter temperatures, steady winds, and summer droughts make vegetation especially prone to desiccation. Rain that lands on sloping bedrock outcrops quickly runs off to lower elevation areas, further contributing to dry conditions and removing accumulated plant debris and small rock debris that could otherwise initiate soil formation. Glades are subject to fires from both lightning and human sources. Both white pine and red pine form a supercanopy and are prime targets for lightning strikes associated with Lake Superior storms. The open structure and elevated position of glades make them ideal places for historic and modern human gathering, which were and are associated with escaped campfires.

Vegetation

Vegetation goes through a slow succession from lichens and mosses in moist rock depressions to gradual establishment of mats of herbaceous vascular plants. As soil gradually develops, these mats begin supporting localized clumps of shrubs and small trees. Dominant trees of the open canopy include stunted red oak (Quercus rubra) and white pine (Pinus strobus). Other common trees, occurring in the scattered and low canopy and also as saplings in the understory, include red pine (P. resinosa), quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides), big-toothed aspen (P. grandidentata), and paper birch (Betula papyrifera). Common shrubs include low sweet blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium), Canada blueberry (V. myrtilloides), bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi), common juniper (Juniperus communis), serviceberry (Amelanchier interior), wild red raspberry (Rubus strigosus), smooth sumac (Rhus glabra), choke cherry (Prunus virginiana), pin cherry (P. pensylvanica), and bush honeysuckle (Diervilla lonicera). Among the commonly occurring forbs are cow-wheat (Melampyrum lineare), slender ladies’-tresses (Spiranthes lacera), large-leaved aster (Eurybia macrophylla), jumpseed (Persicaria virginiana), western smartweed (Polygonum douglasii), wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana), and harebell (Campanula rotundifolia). Commonly occurring graminoids include Pennsylvania sedge (Carex pensylvanica), poverty grass (Danthonia spicata), hair grasses (Avenella flexuosa and Deschampsia cespitosa), rice grass (Piptatherum pungens), and panic grasses (Dichanthelium columbianum, D. depauperatum, and D. linearifolium). Common ferns include rusty woodsia (Woodsia ilvensis), marginal woodfern (Dryopteris marginalis), spinulose woodfern (D. carthusiana), common polypody (Polypodium virginianum), maidenhair spleenwort (Asplenium trichomanes), and bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum). Areas of exposed bedrock are dominated by a diverse array of lichens (e.g., Cladina spp.) and mosses (e.g., Polytrichum spp.).

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Graminoids

- wavy hair grass (Avenella flexuosa)

- Pennsylvania sedge (Carex pensylvanica)

- poverty grass (Danthonia spicata)

- tufted hair grass (Deschampsia cespitosa)

- panic grasses (Dichanthelium columbianum, D. depauperatum, and D. linearifolium)

- rice grass (Piptatherum pungens)

Forbs

- yarrow (Achillea millefolium)

- small pussytoes (Antennaria howellii)

- spreading dogbane (Apocynum androsaemifolium)

- wild columbine (Aquilegia canadensis)

- bristly sarsaparilla (Aralia hispida)

- harebell (Campanula rotundifolia)

- pink corydalis (Capnoides sempervirens)

- trailing arbutus (Epigaea repens)

- large-leaved aster (Eurybia macrophylla)

- wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana)

- cow-wheat (Melampyrum lineare)

- big-leaf sandwort (Moehringia macrophylla)

- jumpseed (Persicaria virginiana)

- western smartweed (Polygonum douglasii)

- three-toothed cinquefoil (Sibbaldiopsis tridentata)

- slender ladies’-tresses (Spiranthes lacera)

Ferns

- maidenhair spleenwort (Asplenium trichomanes)

- spinulose woodfern (Dryopteris carthusiana)

- marginal woodfern (Dryopteris marginalis)

- common polypody (Polypodium virginianum)

- bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum)

- rusty woodsia (Woodsia ilvensis)

Lichens

- reindeer lichens (Cladina spp.)

Mosses

- haircap mosses (Polytrichum spp.)

Woody Vines

- poison-ivy (Toxicodendron radicans)

- riverbank grape (Vitis riparia)

Shrubs

- serviceberries (Amelanchier spp.)

- bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi)

- bush honeysuckle (Diervilla lonicera)

- wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens)

- common juniper (Juniperus communis)

- choke cherry (Prunus virginiana)

- smooth sumac (Rhus glabra)

- northern gooseberry (Ribes oxyacanthoides)

- thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus)

- wild red raspberry (Rubus strigosus)

- low sweet blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium)

- Canada blueberry (Vaccinium myrtilloides)

Trees

- balsam fir (Abies balsamea)

- red maple (Acer rubrum)

- paper birch (Betula papyrifera)

- black hawthorn (Crataegus douglasii)

- white spruce (Picea glauca)

- jack pine (Pinus banksiana)

- red pine (Pinus resinosa)

- white pine (Pinus strobus)

- big-toothed aspen (Populus grandidentata)

- quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides)

- pin cherry (Prunus pensylvanica)

- red oak (Quercus rubra)

- basswood (Tilia americana)

Noteworthy Animals

Ants are quite abundant in this dry, thin-soiled environment. Black bears use this habitat, possibly because of the abundant ants, other insects, and wild fruit.

Rare Plants

- Dryopteris filix-mas (male fern, state special concern)

- Dryopteris fragrans (fragrant cliff woodfern, state special concern)

- Opuntia fragilis (fragile prickly-pear, state endangered)

- Ribes oxyacanthoides (northern gooseberry, state special concern)

- Woodsia alpina (northern woodsia, state threatened)

Rare Animals

- Falco columbarius (merlin, state threatened)

- Falco peregrinus (peregrine falcon, state endangered)

- Haliaeetus leucocephalus (bald eagle, state threatened)

Biodiversity Management Considerations

The thin soils and lichen cover are easily destroyed by off-road vehicles or excessive foot traffic. Many seasonal cabins are built within the glades, resulting in major degradation, including the introduction of non-native plants. Fill is often introduced for septic systems, also increasing habitat for invasive plants. Invasive plants that threaten the diversity and community structure in granite bedrock glade include sheep sorrel (Rumex acetosella), common mullein (Verbascum thapsus), spotted knapweed (Centaurea stoebe), ox-eye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare), hawkweeds (Hieracium spp.), common St. John’s-wort (Hypericum perforatum), timothy (Phleum pratense), Canada bluegrass (Poa compressa), and Kentucky bluegrass (P. pratensis). Monitoring and control efforts to detect and remove invasive plants are critical to the long-term viability of bedrock glades. Maintaining a mature, unfragmented forested buffer around bedrock glades may help limit the local seed source for invasive species distributed by wind or birds.

Open conditions within glades can be maintained by allowing wildfires to move through the community where safety and other conditions permit. Prescribed fire management of adjacent dry-mesic forests should include areas of bedrock glade when feasible.

Variation

Species composition may vary with bedrock type and aspect.

Similar Natural Communities

Northern bald, granite bedrock lakeshore, granite cliff, granite lakeshore cliff, volcanic bedrock glade, volcanic bedrock lakeshore, volcanic cliff, sandstone bedrock lakeshore, sandstone cliff, and dry-mesic northern forest.

Places to Visit

- Lost Creek Outcrops, Gwinn State Forest Management Unit, Marquette Co.

- Lost Lake Outcrops, Crystal Falls State Forest Management Unit, Dickinson Co.

- Sugarloaf Glade, Gwinn State Forest Management Unit, Marquette Co.

- Van Riper Glades, Van Riper State Park, Marquette Co.

Relevant Literature

- Albert, D.A., P. Comer, D. Cuthrell, D. Hyde, W. MacKinnon, M. Penskar, and M. Rabe. 1997. The Great Lakes bedrock lakeshores of Michigan. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 218 pp.

- Catling, P.M., and V.R. Brownell. 1999. The flora and ecology of southern Ontario granite barrens. Pp. 392-405 in Savannas, barrens, and rock outcrop plant communities of North America, ed. R.C. Anderson, J.S. Fralish, and J.M. Baskin. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 480 pp.

- Dorr, J.A., Jr., and D.F. Eschman. 1970. Geology of Michigan. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI. 470 pp.

- Faber-Langendoen, D., ed. 2001. Plant communities of the Midwest: Classification in an ecological context. Association for Biodiversity Information, Arlington, VA. 61 pp. + appendix (705 pp.).

- Given, D.R., and J.H. Soper. 1981. The arctic-alpine element of the vascular flora at Lake Superior. National Museums of Canada, Publication in Botany 10: 1-70.

- LaBerge, G.L. 1994. Geology of the Lake Superior region. Geoscience Press, Phoenix, AZ. 313 pp.

- Reed, R.C., and J. Daniels. 1987. Bedrock geology of northern Michigan. State of Michigan Department of Natural Resources. Map: 1: 500,000.

- Shure, D.J. 1999. Granite outcrops of the southeastern United States. Pp. 99-118 in Savannas, barrens, and rock outcrop plant communities of North America, ed. R.C. Anderson, J.S. Fralish, and J.M. Baskin. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 480 pp.

- Simpson, T.B., P.E. Stuart, and B.V. Barnes. 1990. Landscape ecosystems and cover types of the reserve area and adjacent lands of the Huron Mountain Club. Occasional Papers of the Huron Mountain Wildlife Foundation, Number 4. 128 pp.

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: February 24, 2026).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.