Limestone Lakeshore Cliff

Overview

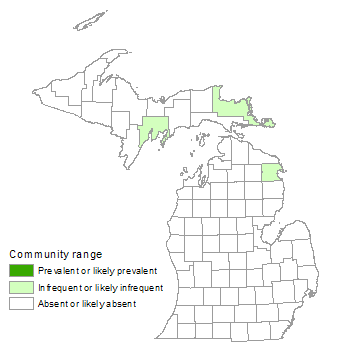

Limestone lakeshore cliff consists of vertical or near-vertical exposures of bedrock, which typically support less than 25% vascular plant coverage, although some rock surfaces can be densely covered with lichens, mosses, and liverworts. The community occurs in the Upper Peninsula along the shorelines of Lake Michigan and Lake Huron. Like all of Michigan’s lakeshore cliffs, vegetation cover is sparse but abundant cracks and crevices combined with calcareous conditions result in greater plant diversity and coverage than on most other cliff types. Limestone lakeshore cliffs are characterized by high site moisture due to the proximity to the Great Lakes and a stressed and unstable environment because of severe waves, wind, and winter ice.

Rank

Global Rank: G4G5 - Rank is uncertain, ranging from apparently secure to secure

State Rank: S1 - Critically imperiled

Landscape Context

Limestone and dolomite cliffs are scattered along the Niagaran Escarpment, from the Garden Peninsula on northwestern Lake Michigan to Mackinac and Drummond Islands in northern Lake Huron. Limestone cliffs extend farther west in Lake Michigan to the Door Peninsula of Wisconsin and farther east to the Bruce Peninsula of northern Lake Huron and Georgian Bay and on into northern Lake Ontario. In Michigan, limestone lakeshore cliff is typically bordered along its inland margin by boreal forest, mesic northern forest, or occasionally dry-mesic northern forest. Along the lakeshore, the community may border limestone bedrock lakeshore, limestone cobble shore, and sand and gravel beach.

Soils

Soil development is primarily limited to thin organic soils that form from decaying roots and other plant materials along the top of the cliff escarpment and ledges, in cracks and crevices in the bedrock, and at the base of the cliff. Breakdown of limestone and plant debris results in a sandy to loamy, organic-rich soil, with mildly alkaline pH.

Natural Processes

The vertical structure of cliffs causes constant erosion and restricts soil development to the cliff edge, cracks, ledges, and the base of the cliff where organic matter and soil particles can accumulate. The thin soils and direct exposure to wind, ice, and sun produce desiccating conditions that limit plant growth. However, cliff aspect and local seepages result in a variability of site moisture conditions. North- and east-facing cliffs are typically moister than south- and west-facing cliffs because of reduced wind and reduced direct exposure to the sun. Moisture can be locally present on cliff faces due to local groundwater seepage along the cliff face or surface flow across the cliff face during rain events or snow melt. Weathering results in the gradual exfoliation of exposed limestone along the cliff face, which adds to the instability of the ecosystem, reducing dependable habitat for plant establishment. As portions of the bedrock slough off, they form talus slopes of boulders and slabs along the base of cliffs and expose fresh, bare rock substrates along the cliff face. Windthrow of canopy trees along the cliff escarpment is common due to the thin soils, unstable substrate, and high wind activity. Windblown trees along ledges and at the base of the cliff provide localized areas for soil accumulation.

Vegetation

While lichens, mosses, and liverworts are common on the exposed cliff face, vascular plant cover is sparse, being generally restricted to the flat, exposed bedrock at the upper edge of the cliff (i.e., lip), cracks, joints, and ledges in the cliff face, and along the cliff base if a ledge of talus, cobble, sand, or bedrock is present between the cliff and the open water. Lichens, mosses, and liverworts are especially abundant on moist seepages and cooler north aspects. The forested ridge tops support species such as red oak (Quercus rubra), sugar maple (Acer saccharum), northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis), balsam fir (Abies balsamea), and paper birch (Betula papyrifera). Common herbaceous plants occurring at the cliff edge and in the cliff-top forests include common polypody (Polypodium virginianum), large-leaved aster (Eurybia macrophylla), wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana), Canada mayflower (Maianthemum canadense), and wild sarsaparilla (Aralia nudicaulis). On the open cliff face the vegetation cover is sparse. Common tree species on the cliff face are northern white-cedar and paper birch, both species that root in crevices in the rock. Small, misshapen northern white-cedars over 1,000 years old have been found growing on the cliff faces near Fayette State Park. Balsam fir is often present in the subcanopy and understory. Ferns are prevalent along the cliff face, especially along moist exposures. Characteristic ferns include common polypody, fragile fern (Cystopteris fragilis), smooth cliff brake (Pellaea glabella), maidenhair spleenwort (Asplenium trichomanes), bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum), Oregon woodsia (Woodsia oregana), and wall-rue (Asplenium ruta-muraria, state endangered). Common herbs on the cliff face include grass-leaved goldenrod (Euthamia graminifolia), herb Robert (Geranium robertianum), wild columbine (Aquilegia canadensis), yarrow (Achillea millefolium), and rock whitlow-grass (Draba arabisans, state special concern). Scattered and often stunted shrubs on the cliffs include soapberry (Shepherdia canadensis), bush honeysuckle (Diervilla lonicera), thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus), mountain maple (Acer spicatum), choke cherry (Prunus virginiana), and red elderberry (Sambucus racemosa). These shrubs are also found scattered on talus at the base of the cliff. Several invasive plants commonly establish on the open cliffs, including common mullein (Verbascum thapsus), hound’s-tongue (Cynoglossum officinale), bittersweet nightshade (Solanum dulcamara), and ox-eye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare). Recently, cryptoendolithic species of algae have been found to grow within the structure of the rock, creating the dark surface color of limestone rock.

Studies of limestone cliffs in Ontario found that there were three distinct zones of vegetation that share few species: ridge-top forest, cliff face, and talus. This zonation is also apparent in many Michigan limestone cliff systems; however, where the vertical height of the cliffs is low, there is a significant overlap in terms of species composition among the zones.

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Graminoids

- beauty sedge (Carex concinna)

- ebony sedge (Carex eburnea)

Forbs

- yarrow (Achillea millefolium)

- wild columbine (Aquilegia canadensis)

- wild sarsaparilla (Aralia nudicaulis)

- rock whitlow-grass (Draba arabisans)

- large-leaved aster (Eurybia macrophylla)

- grass-leaved goldenrod (Euthamia graminifolia)

- wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana)

- herb Robert (Geranium robertianum)

- Canada mayflower (Maianthemum canadense)

Ferns

- maidenhair spleenwort (Asplenium trichomanes)

- slender rock-brake (Cryptogramma stelleri)

- fragile fern (Cystopteris fragilis)

- oak fern (Gymnocarpium dryopteris)

- limestone oak fern (Gymnocarpium robertianum)

- purple cliff-brake (Pellaea atropurpurea)

- smooth cliff-brake (Pellaea glabella)

- common polypody (Polypodium virginianum)

- bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum)

- Oregon woodsia (Woodsia oregana)

Shrubs

- beaked hazelnut (Corylus cornuta)

- bush honeysuckle (Diervilla lonicera)

- Canadian fly honeysuckle (Lonicera canadensis)

- choke cherry (Prunus virginiana)

- thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus)

- red elderberry (Sambucus racemosa)

- soapberry (Shepherdia canadensis)

Trees

- balsam fir (Abies balsamea)

- sugar maple (Acer saccharum)

- mountain maple (Acer spicatum)

- paper birch (Betula papyrifera)

- white pine (Pinus strobus)

- red oak (Quercus rubra)

- northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis)

- hemlock (Tsuga canadensis)

Noteworthy Animals

Large crevices in cliffs provide hibernacula for bats (Myotis spp.) and snakes, including eastern garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis), western fox snake (Elaphe vulpna), and northern ring-necked snake (Diadophis punctatus edwardsii). Birds found commonly nesting on limestone and dolomite cliffs include American goldfinch (Carduelis tristis), Nashville warbler (Vermivora ruficapilla), and cliff swallow (Petrochelidon pyrrhonota). White-footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopus), deer mouse (P. maniculatus), and raccoon (Procyon lotor) also frequently utilize the cliffs. Eastern chipmunks (Tamais striatus) and other rodents burrow and nest in the protected habitat of the talus. Caddisflies (Trichoptera), mosquitoes (Culicidae), and solitary midges (Thaumaleidae) are found associated with continuous seepage areas on cliffs, and many species of spider (Arachnida) are common as well.

Rare Plants

- Asplenium rhizophyllum (walking fern, state threatened)

- Asplenium ruta-muraria (wall-rue, state endangered)

- Asplenium scolopendrium var. americanum (Hart’s-tongue fern, state endangered)

- Asplenium trichomanes-ramosum (green spleenwort, state threatened)

- Astragalus neglectus (Cooper’s milk vetch, state special concern)

- Braya humilis (low northern rock-cress, state threatened)

- Draba arabisans (rock whitlow-grass, state special concern)

- Draba cana (ashy whitlow-grass, state threatened)

- Dryopteris filix-mas (male fern, state special concern)

- Pellaea atropurpurea (purple cliff-brake, state special concern)

- Woodsia alpina (northern woodsia, state special concern)

Rare Animals

- Falco columbarius (merlin, state threatened)

- Falco peregrinus (Peregrine falcon, state endangered)

- Haliaeetus leucocephalus (bald eagle, state threatened)

- Vertigo bollesiana (delicate vertigo, state special concern)

- Vertigo cristata (land snail, state special concern)

- Vertigo paradoxa (land snail, state special concern)

Biodiversity Management Considerations

Threats to lakeshore cliffs include shoreline development, logging of adjacent uplands and associated soil erosion, excessive foot traffic along the upper edge, rock climbing, and invasive plants. The thin soils and unstable cliff environment make soil development and plant reestablishment slow, highlighting the importance of minimizing logging and excessive trampling along the upper edge of cliffs. Rock climbing can result in damage and loss of vegetation on the cliff face as many lichens and mosses of the cliffs have extremely slow recovery rates. Maintaining a mature, unfragmented forested buffer around limestone lakeshore cliffs may help limit the local seed source for invasive species distributed by wind or birds. Some of the invasive plants that may threaten the diversity and structure of limestone lakeshore cliffs include spotted knapweed (Centaurea stoebe), ox-eye daisy, Canada bluegrass (Poa compressa), Kentucky bluegrass (P. pratensis), sheep sorrel (Rumex acetosella), hawkweeds (Hieracium spp.), common mullein, hound’s-tongue, and bittersweet nightshade. Monitoring and control efforts to detect and remove these and other invasive species will help maintain the ecological integrity of limestone lakeshore cliff and surrounding natural communities.

Variation

The limestone is quite variable across the Niagaran Escarpment, including magnesium-rich limestone (i.e., dolomite) and argillaceous or muddy limestone. These chemical differences result in different physical appearance and characteristics, such as hardness and amount and size of crevices. These physical and chemical differences translate to different habitat characteristics and species composition.

Similar Natural Communities

Limestone cliff, sandstone lakeshore cliff, volcanic lakeshore cliff, granite lakeshore cliff, granite cliff, sandstone cliff, limestone bedrock glade, limestone bedrock lakeshore, and volcanic cliff.

Places to Visit

- Burnt Bluff (Garden Peninsula), Fayette Historic State Park, Delta Co.

- Middle Bluff (Garden Peninsula), Shingleton State Forest Management Unit and Fayette Historic State Park, Delta Co.

- Poe Point (Drummond Island), Maxton Plains Preserve, The Nature Conservancy, Chippewa Co.

Relevant Literature

- Albert, D.A., P. Comer, D. Cuthrell, D. Hyde, W. MacKinnon, M. Penskar, and M. Rabe. 1997. The Great Lakes bedrock lakeshores of Michigan. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 218 pp.

- Dorr, J.A., Jr., and D.F. Eschman. 1970. Geology of Michigan. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI. 470 pp.

- Faber-Langendoen, D., ed. 2001. Plant communities of the Midwest: Classification in an ecological context. Association for Biodiversity Information, Arlington, VA. 61 pp. + appendix (705 pp.).

- Lawson, D.W., U. Matthes-Sears, and P.E. Kelly. 1999. The cliff ecosystems of the Niagara Escarpment. Pp. 362-374 in Savannas, barrens, and rock outcrop plant communities of North America, ed. R.C. Anderson, J.S. Fralish, and J.M. Baskin. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 480 pp.

- Reschke, C., R. Reid, J. Jones, T. Feeney, and H. Potter. 1999. Conserving Great Lakes alvar: Final technical report of the International Alvar Conservation Initiative. The Nature Conservancy, Chicago, IL. 241 pp.

- Thompson, E.H., and E.R. Sorenson. 2005. Wetland, woodland, and wildland: A guide to the natural communities of Vermont. The Nature Conservancy and Vermont Department of Fish and Game. University Press of New England, Lebanon, NH. 456 pp.

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: February 3, 2026).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.