Volcanic Cliff

Overview

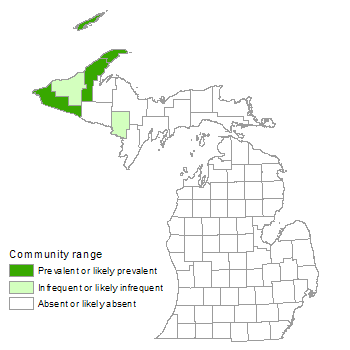

Volcanic cliffs consist of vertical or near-vertical exposures of bedrock, which support less than 25% vascular plant coverage, although lichens, mosses, and liverworts are abundant on some rock surfaces. The cliffs can be as high as 80 m (260 ft) and occur on inland exposures of the resistant Middle Keweenawan volcanic rock, which runs from the north tip of the Keweenaw Peninsula south into Wisconsin and also along the entire length of Isle Royale.

Rank

Global Rank: G4G5 - Rank is uncertain, ranging from apparently secure to secure

State Rank: S2 - Imperiled

Landscape Context

The bedrock of the Keweenaw Peninsula dips steeply toward the north and into Lake Superior, while the south face of the bedrock forms cliffs. The cliffs vary from only a few meters high to over 80 m (260 ft) high. On the Keweenaw Peninsula, most of the cliffs are formed of massive basalt, but there are also some areas of cliff composed of volcanic conglomerate rock. Some of the highest and most extensive cliffs are associated with the Greenstone Flow, part of the Portage Lake Volcanics. Cliffs of the Greenstone Flow can be seen in Keweenaw County along US Highway 41, from the towns of Allouez and Ahmeek in the south to the towns of Delaware and Mandan in the north. The Greenstone Flow also forms inland cliffs parallel to the south shore of Isle Royale. Other large expanses of cliff are associated with the resistant Copper Harbor Conglomerate, of which some of the best known sites are Brockway and Lookout Mountains. Other large cliffs are associated with the interface of the Portage Lake Volcanics and the Jacobsville Sandstones, as seen at Mt. Bohemia.

Volcanic cliff also occurs in Ontario, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. In Michigan, volcanic cliff is typically bordered by boreal forest and occasionally by dry-mesic northern forest, mesic northern forest, or volcanic bedrock glade.

Soils

There is little soil development on the steep rock face of the cliffs. Some organic soil development occurs in crevices in the rock face, on the upper lip of the cliffs, and at the base of the cliff face.

Natural Processes

The combination of vertical exposure, thin soils, strong winds, and ice maintain open conditions on the cliff face. The cliffs are exposed to extreme storm winds, often from Lake Superior. Storm winds uproot trees and erode soils. Windblown trees at the base of the cliff provide localized areas for soil accumulation. Thin soils, winter winds, full exposure, and summer droughts produce a desiccating environment for plants. The regularly occurring fog from nearby Lake Superior may partially mitigate these desiccating effects during the growing season.

Vegetation

While mosses and lichens are common on the exposed cliff face, vascular plant cover is sparse, being generally restricted to the flat, exposed bedrock at the upper edge of the cliff (i.e., lip), cracks and joints in the cliff face, and along the cliff base, where a talus slope typically develops. The upper edge of the cliff is typically backed by boreal forest, dry-mesic northern forest, or mesic northern forest, with abundant windthrown trees resulting from strong winds. Herbaceous species characteristic of the upper flat edge or lip include harebell (Campanula rotundifolia), balsam ragwort (Packera paupercula), wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana), early saxifrage (Micranthes virginiensis), yarrow (Achillea millefolium), hair grass (Deschampsia cespitosa), and the invasive species Canada bluegrass (Poa compressa). Shrubs occurring along the upper lip include soapberry (Shepherdia canadensis), serviceberries (Amelanchier spp.), and wild rose (Rosa acicularis). Some of the few plants that occur on the cliff face are occasional patches of common polypody (Polypodium virginianum), harebell, and hair grass. Shrub-sized red oak (Quercus rubra) and paper birch (Betula papyrifera) occur on the summits of some of the inland cliffs. Their dwarf size is the result of strong winds and ice storms.

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Graminoids

- poverty grass (Danthonia spicata)

- tufted hair grass (Deschampsia cespitosa)

Forbs

- yarrow (Achillea millefolium)

- wild columbine (Aquilegia canadensis)

- wild sarsaparilla (Aralia nudicaulis)

- wormwood (Artemisia campestris)

- low bindweed (Calystegia spithamea)

- harebell (Campanula rotundifolia)

- fireweed (Chamerion angustifolium)

- bluebead lily (Clintonia borealis)

- small blue-eyed Mary (Collinsia parviflora)

- large-leaved aster (Eurybia macrophylla)

- wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana)

- early saxifrage (Micranthes virginiensis)

- balsam ragwort (Packera paupercula)

- downy Solomon seal (Polygonatum pubescens)

Ferns

- maidenhair spleenwort (Asplenium trichomanes)

- common polypody (Polypodium virginianum)

- rusty woodsia (Woodsia ilvensis)

Woody Vines

- poison-ivy (Toxicodendron radicans)

- riverbank grape (Vitis riparia)

Shrubs

- serviceberries (Amelanchier spp.)

- bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi)

- redstem ceanothus (Ceanothus sanguineus)

- bush honeysuckle (Diervilla lonicera)

- common juniper (Juniperus communis)

- ninebark (Physocarpus opulifolius)

- choke cherry (Prunus virginiana)

- staghorn sumac (Rhus typhina)

- wild rose (Rosa acicularis)

- red elderberry (Sambucus racemosa)

- soapberry (Shepherdia canadensis)

- snowberry (Symphoricarpos albus)

Trees

- balsam fir (Abies balsamea)

- sugar maple (Acer saccharum)

- mountain maple (Acer spicatum)

- serviceberries (Amelanchier spp.)

- yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis)

- paper birch (Betula papyrifera)

- ironwood (Ostrya virginiana)

- white pine (Pinus strobus)

- red oak (Quercus rubra)

- northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis)

- basswood (Tilia americana)

Noteworthy Animals

Cliffs provide nesting habitat for raptors and common raven (Corvus corax).

Rare Plants

- Asplenium montanum (mountain spleenwort, presumed extirpated from Michigan)

- Ceanothus sanguineus (wild-lilac, state threatened)

- Chamaerhodos nuttallii var. keweenawensis (Keweenaw rock-rose, state endangered)

- Collinsia parviflora (small blue-eyed Mary, state threatened)

- Danthonia intermedia (wild oat-grass, state special concern)

- Draba arabisans (rock whitlow-grass, state special concern)

- Draba cana (ashy whitlow-grass, state threatened)

- Muhlenbergia cuspidata (plains muhly, presumed extirpated from Michigan)

- Pellaea atropurpurea (purple cliff-brake, state special concern)

- Poa canbyi (Canby’s bluegrass, state threatened)

- Saxifraga paniculata (encrusted saxifrage, state threatened)

- Senecio indecorus (rayless mountain ragwort, state threatened)

- Trisetum spicatum (downy oatgrass, state special concern)

- Woodsia alpina (northern woodsia, state threatened)

- Woodsia obtusa (blunt-lobed woodsia, state threatened)

Rare Animals

- Falco columbarius (merlin, state threatened)

- Falco peregrinus (Peregrine falcon, state endangered)

- Haliaeetus leucocephalus (bald eagle, state threatened)

- Planogyra asteriscus (eastern flat-whorl, state special concern)

- Vertigo bollesiana (delicate vertigo, state special concern)

- Vertigo cristata (land snail, state special concern)

- Vertigo modesta (cross vertigo, state special concern)

- Vertigo modesta parietalis (land snail, state special concern)

- Vertigo paradoxa (land snail, state special concern)

Biodiversity Management Considerations

Threats to volcanic cliffs include development, logging of adjacent uplands and associated soil erosion, excessive foot traffic along the upper edge, and invasive plants. The thin soils and unstable environment make soil development and plant reestablishment slow, highlighting the importance of minimizing logging and excessive trampling along the upper edge of cliffs. Maintaining a mature, unfragmented forested buffer around volcanic cliff may help limit the local seed source for invasive species distributed by wind or birds. Some of the invasive plants that may threaten the diversity and structure of volcanic cliffs include spotted knapweed (Centaurea stoebe), ox-eye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare), Canada bluegrass (Poa compressa), Kentucky bluegrass (P. pratensis), sheep sorrel (Rumex acetosella), and hawkweeds (Hieracium spp.). Monitoring and control efforts to detect and remove these and other invasive species will help maintain the ecological integrity of volcanic cliff and surrounding natural communities.

Variation

Cliffs occur on both volcanic conglomerate and massive basalt. Vegetation diversity appears to be higher on the conglomerate substrate.

Similar Natural Communities

Granite cliff, limestone cliff, sandstone cliff, granite bedrock glade, volcanic bedrock glade, volcanic lakeshore cliff, and northern bald.

Places to Visit

- Bare Bluffs Cliffs, Michigan Nature Association (Grinnell Memorial Sanctuary at Bare Bluff), Keweenaw Co.

- Escarpment Trail Cliffs, Porcupine Mountains Wilderness State Park, Gogebic Co. and Ontonagon Co.

- Isle Royale National Park, Keweenaw Co.

- Traps Hills Escarpment, Ottawa National Forest, Ontonagon Co.

Relevant Literature

- Albert, D.A., P. Comer, D. Cuthrell, D. Hyde, W. MacKinnon, M. Penskar, and M. Rabe. 1997. The Great Lakes bedrock lakeshores of Michigan. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 218 pp.

- Bornhorst, T.J., and W.I. Rose. 1994. Self-guided geological field trip to the Keweenaw Peninsula, Michigan. Proceedings of the Institute on Lake Superior Geology. Volume 40, Part 2. 185 pp.

- Dorr, J.A., Jr., and D.F. Eschman. 1970. Geology of Michigan. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI. 470 pp.

- Faber-Langendoen, D., ed. 2001. Plant communities of the Midwest: Classification in an ecological context. Association for Biodiversity Information, Arlington, VA. 61 pp. + appendix (705 pp.).

- Given, D.R., and J.H. Soper. 1981. The arctic-alpine element of the vascular flora at Lake Superior. National Museums of Canada, Publication in Botany 10: 1-70.

- LaBerge, G.L. 1994. Geology of the Lake Superior region. Geoscience Press, Phoenix, AZ. 313 pp.

- Little, R.J. 2005. Parks and plates: The geology of our national parks, monuments, and seashores. W.W. Norton, New York, NY. 298 pp.

- Reed, R.C., and J. Daniels. 1987. Bedrock geology of northern Michigan. State of Michigan Department of Natural Resources. Map: 1: 500,000.

- Reschke, C. 1985. Vegetation of the conglomerate rock shoreline of the Keweenaw Peninsula, northern Michigan. M.S. thesis. University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI. 118 pp.

- Slavick, A.D., and R.A. Janke. 1987. The vascular flora of Isle Royale National Park. Michigan Botanist 26: 91-134.

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: March 13, 2026).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.