Granite Cliff

Overview

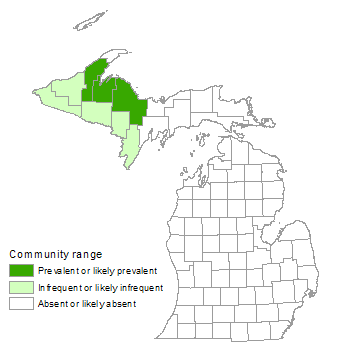

Granite cliff consists of vertical or near-vertical exposures of bedrock with sparse coverage of vascular plants, lichens, mosses, and liverworts. The community occurs in several counties of the western Upper Peninsula, including Dickinson, Gogebic, Houghton, Iron, Marquette, and Menominee.

Rank

Global Rank: G4G5 - Rank is uncertain, ranging from apparently secure to secure

State Rank: S2 - Imperiled

Landscape Context

A broad range of igneous and metamorphic rock, including gneiss, schist, granite, and quartzite, are often loosely referred to as “granitic” or “granite.” Granite cliff is composed of resistant igneous and metamorphic bedrock types of the Michigamme Highlands that formed during the Precambrian Era, approximately 3,500 to 600 million years ago. The community is also present in nearby Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Ontario. Along its margins, granite cliff is typically bordered by boreal forest, dry-mesic northern forest, mesic northern forest, or granite bedrock glade. Wetlands sometimes occur at the base of cliffs and include rich conifer swamp, poor conifer swamp, and northern shrub thicket. Cliff exposures that occur along Lake Superior are classified as granite lakeshore cliff. Among the largest expanses of inland cliffs is Mulligan Cliffs in Marquette County, which is several miles long and ranges in height from 22 to 46 m (60 to 130 feet).

Soils

Soil development is limited to shallow organic soils that form from decaying roots and other plant material that accumulates in cracks, crevices, ledges, and flat areas or depressions in the bedrock. Soils accumulate primarily along the cliff summit, on talus slopes, and at the base of the cliff. The thin organic soils are typically acid but can range from slightly acid to slightly alkaline depending on the rock type.

Natural Processes

The combination of vertical exposure, thin soils, strong winds, ice, and bedrock exfoliation maintain open conditions on the cliff face. The thin soils and full exposure to wind and sun produce desiccating conditions for many plants. Mosses and lichens establish on more protected rock surfaces, while vascular plants are restricted to crevices, ledges, or moisture-holding depressions in the rock. Granitic rock, formed under intense pressure deep within the earth’s crust, exfoliates when it is exposed at the surface. Exfoliation adds to the instability of the ecosystem, reducing dependable habitat for plant establishment. As portions of the bedrock slough off, they form talus slopes along the base of cliffs and expose fresh, bare rock substrates along the cliff face. Windthrow of canopy trees along the cliff escarpment is common due to the thin soils, unstable substrate, and high wind activity. Windblown trees along ledges and at the base of the cliff provide localized areas for soil accumulation. In addition, lightning strikes can generate localized fires along the cliff face and also at the base of the cliff where conifer canopy is most prevalent.

Vegetation

While mosses and lichens can be common on the exposed cliff face, vascular plant cover is sparse, being generally restricted to the flat, exposed bedrock at the upper edge of the cliff (i.e., lip), cracks and crevices in the cliff face, ledges, and terraces that interrupt the vertical exposure, and along the cliff base, where a talus slope typically develops. Prevalent canopy species along the cliff face include white pine (Pinus strobus), jack pine (P. banksiana), and red pine (P. resinosa), with canopy associates including red oak (Quercus rubra) and big-toothed aspen (Populus grandidentata). At the upper edge of the cliff, there can be krummholz (i.e., low, misshapen) or flagged trees. Paper birch (Betula papyrifera), choke cherry (Prunus virginiana), and serviceberries (Amelanchier spp.) also occur in this zone. Characteristic shrubs include low sweet blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium), bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi), common juniper (Juniperus communis), and bush honeysuckle (Diervilla lonicera). Among the more common plants of the sparse ground layer are hair grass (Avenella flexuosa), poverty grass (Danthonia spicata), three-toothed cinquefoil (Sibbaldiopsis tridentata), bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum), Canada mayflower (Maianthemum canadense), and large-leaved aster (Eurybia macrophylla). The top of the cliff is often an open glade, with scattered, open-grown, and occasionally flagged trees growing on bedrock or thin soil.

Ledges and cracks along the cliff face support sparse vegetation with occasional stunted trees and shrubs including northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis), paper birch, red pine, choke cherry, and serviceberries, and scattered clumps of low shrubs such as bearberry, common juniper, bush honeysuckle, and raspberries (Rubus spp.). Ferns are prevalent along the moist ledges and protected fissures and include common polypody (Polypodium virginianum), smooth cliff brake (Pellaea glabella), maidenhair spleenwort (Asplenium trichomanes), and rusty woodsia (Woodsia ilvensis). Characteristic herbaceous species include wild columbine (Aquilegia canadensis), wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana), rock whitlow-grass (Draba arabisans, state special concern), and downy Solomon’s seal (Polygonatum pubescens).

Areas of talus slope, concentrated at the base of the cliff, are characterized by sparse vegetation as well with scattered and stunted trees and tall shrubs including northern white-cedar, paper birch, white pine, white spruce (Picea glauca), balsam fir (Abies balsamea), quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides), choke cherry (Prunus virginiana), and serviceberries. The low shrub layer is often the most dense stratum in this zone, particularly in areas of high slope near the base of the cliff face. Dominant species of the low shrub layer and ground cover include stunted choke cherry, bush honeysuckle, thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus), poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), and common polypody. Areas of extensive or recent rock slide are often devoid of vegetation except for lichens encrusted on boulders.

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Graminoids

- poverty grass (Danthonia spicata)

- tufted hair grass (Deschampsia cespitosa)

Forbs

- small-leaved pussytoes (Antennaria neglecta)

- wild columbine (Aquilegia canadensis)

- wild sarsaparilla (Aralia nudicaulis)

- bluebead lily (Clintonia borealis)

- rock whitlow-grass (Draba arabisans)

- large-leaved aster (Eurybia macrophylla)

- wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana)

- Canada mayflower (Maianthemum canadense)

- downy Solomon seal (Polygonatum pubescens)

- three-toothed cinquefoil (Sibbaldiopsis tridentata)

- twisted-stalks (Streptopus spp.)

Ferns

- maidenhair spleenwort (Asplenium trichomanes)

- fragrant woodfern (Dryopteris fragrans)

- marginal woodfern (Dryopteris marginalis)

- oak fern (Gymnocarpium dryopteris)

- smooth cliff-brake (Pellaea glabella)

- common polypody (Polypodium virginianum)

- bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum)

- rusty woodsia (Woodsia ilvensis)

Woody Vines

- red honeysuckle (Lonicera dioica)

- poison-ivy (Toxicodendron radicans)

Shrubs

- serviceberries (Amelanchier spp.)

- bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi)

- bunchberry (Cornus canadensis)

- bush honeysuckle (Diervilla lonicera)

- wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens)

- common juniper (Juniperus communis)

- Canadian fly honeysuckle (Lonicera canadensis)

- choke cherry (Prunus virginiana)

- thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus)

- dwarf raspberry (Rubus pubescens)

- wild red raspberry (Rubus strigosus)

- low sweet blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium)

Trees

- balsam fir (Abies balsamea)

- sugar maple (Acer saccharum)

- mountain maple (Acer spicatum)

- serviceberries (Amelanchier spp.)

- paper birch (Betula papyrifera)

- white spruce (Picea glauca)

- jack pine (Pinus banksiana)

- red pine (Pinus resinosa)

- white pine (Pinus strobus)

- big-toothed aspen (Populus grandidentata)

- quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides)

- red oak (Quercus rubra)

- northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis)

Noteworthy Animals

Cliffs provide nesting habitat for raptors and common ravens (Corvus corax).

Rare Plants

- Dryopteris filix-mas (male fern, state special concern)

- Dryopteris fragrans (fragrant cliff woodfern, state special concern)

- Gymnocarpium jessoense (northern oak fern, state special concern)

- Huperzia appalachiana (mountain fir-moss, state special concern)

- Pterospora andromedea (pine-drops, state threatened)

Rare Animals

- Falco columbarius (merlin, state threatened)

- Falco peregrinus (peregrine falcon, state endangered)

- Haliaeetus leucocephalus (bald eagle, state threatened)

Biodiversity Management Considerations

Threats to cliffs include logging of adjacent uplands and associated soil erosion, excessive foot traffic along the upper edge, rock climbing, and invasive plants. The thin soils and unstable environment make soil development and plant reestablishment slow, highlighting the importance of minimizing logging and excessive trampling along the upper edge of cliffs. Maintaining a mature, unfragmented forested buffer around granite cliff may help limit the local seed source for invasive species distributed by wind or birds. Some of the invasive plants that may threaten the biodiversity of granite cliffs include spotted knapweed (Centaurea stoebe), ox-eye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare), Canada bluegrass (Poa compressa), Kentucky bluegrass (P. pratensis), sheep sorrel (Rumex acetosella), and hawkweeds (Hieracium spp.). Monitoring and control efforts to detect and remove these and other invasive species will help maintain the ecological integrity of granite cliff and surrounding natural communities.

Variation

Several types of bedrock are included within this plant community in Michigan, including granite, gneiss, quartzite, and probably several other types of metamorphic rock.

Similar Natural Communities

Volcanic cliff, limestone cliff, sandstone cliff, granite lakeshore cliff, volcanic lakeshore cliff, sandstone lakeshore cliff, limestone lakeshore cliff, granite bedrock glade, volcanic bedrock glade, and northern bald.

Places to Visit

- Lost Lake Outcrops, Crystal Falls State Forest Management Unit, Dickinson Co.

- Mulligan Cliffs, Gwinn State Forest Management Unit, Marquette Co.

- Van Riper Cliffs, Van Riper State Park, Marquette Co.

Relevant Literature

- Albert, D.A., P. Comer, D. Cuthrell, D. Hyde, W. MacKinnon, M. Penskar, and M. Rabe. 1997. The Great Lakes bedrock lakeshores of Michigan. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 218 pp.

- Dorr, J.A., Jr., and D.F. Eschman. 1970. Geology of Michigan. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI. 470 pp.

- Faber-Langendoen, D., ed. 2001. Plant communities of the Midwest: Classification in an ecological context. Association for Biodiversity Information, Arlington, VA. 61 pp. + appendix (705 pp.).

- LaBerge, G.L. 1994. Geology of the Lake Superior region. Geoscience Press, Phoenix, AZ. 313 pp.

- Reed, R.C., and J. Daniels. 1987. Bedrock geology of northern Michigan. State of Michigan Department of Natural Resources. Map: 1: 500,000.

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: January 25, 2026).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.