Limestone Bedrock Lakeshore

Overview

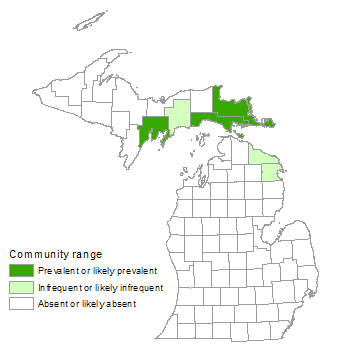

Limestone bedrock lakeshore is a sparsely vegetated natural community dominated by lichens, mosses, and herbaceous vegetation. This community, which is also referred to as alvar pavement and limestone pavement lakeshore, occurs along the shorelines of northern Lake Michigan and Lake Huron on broad, flat, horizontally bedded expanses of limestone or dolomite bedrock. On the Lake Michigan shoreline, limestone bedrock lakeshore is concentrated along the Garden Peninsula and the southern part of Schoolcraft County. Along Lake Huron, it is located east of the Les Cheneaux Islands, on Drummond Island, and on Thunder Bay Island.

Rank

Global Rank: G3 - Vulnerable

State Rank: S2 - Imperiled

Landscape Context

The bedrock includes both limestone and dolomite (or dolostone) of marine origin. Limestone bedrock lakeshores of Michigan occur where flat bedrock of the Niagaran Escarpment is exposed. Bedrock is of Middle and Late Ordovician and Early Silurian origin (405 to 500 million years ago), when shallow, inland seas covered the Lake Michigan Basin. Shoreline bedrock of Thunder Bay Island dates to the more recent Devonian period (345 to 405 million years ago). A veneer of locally derived limestone cobbles of varying thickness occurs along large stretches of limestone bedrock shorelines. Along the inland margins of the limestone pavement, there is often a low ridge of limestone cobble deposited by ice scour and major storm events.

Along the shoreline the community may be interspersed with areas of limestone cobble shore and sand and gravel beach. Other associated shoreline communities in areas of limestone bedrock lakeshore include coastal fen and Great Lakes marsh. Along the inland margin, limestone bedrock lakeshore is typically bordered by boreal forest or mesic northern forest and less commonly by limestone bedrock glade, alvar, or rich conifer swamp.

Soils

Almost no soil development takes place directly on the limestone pavement, where storm waves and ice routinely scour the rock surface. Consequently, plant establishment is generally limited to cracks, joints, and depressions in the bedrock, where small amounts of organic matter, cobble, and finer sediments accumulate. Because it is formed from marine organisms, limestone bedrock is rich in calcium carbonates, resulting in a mildly alkaline soil pH. Resistance of the bedrock to erosion is variable. Both limestone and dolostone are readily dissolved by rainwater, producing solution depressions and cracks that often connect to the underlying groundwater system. However, limestone rich in mineral soil particles originating from terrestrial sources is resistant to solution and typically contains few cracks.

Natural Processes

Storms, wind, winter ice scour, fluctuating water levels, and severe desiccation produce a stressful, unstable environment for vegetation establishment and growth. During storms, flooding, pounding waves, and high winds rearrange large boulders, smaller rocks, and fine sediments, eliminating local pockets of vegetation and creating new habitat patches for plant establishment. Winter ice scour scrapes clean smooth areas of bedrock and deposits fresh loads of boulders, cobble, and sediments as the ice and snow melt. Thin soils, full exposure, and high winds combine to produce severely desiccating conditions, especially during summer dry periods. Changes in Great Lakes water levels result in vegetation colonizing recently exposed shorelines during periods of low water only to be submerged and often eliminated during periods of high water. Windthrow is common along the upland margin, where trees are able to mature but are shallowly rooted in the thin soils overlying the bedrock.

Vegetation

Limestone bedrock lakeshore is a sparsely vegetated community supporting a flora tolerant of mildly alkaline conditions and frequent disturbance. The community is dominated by herbaceous plants, mosses, and lichens, with tree cover generally limited to the inland edge. Characteristic herbaceous plants, in order of number of occurrences observed during surveys of the community, include low calamint (Clinopodium arkansanum), hair grass (Deschampsia cespitosa), Baltic rush (Juncus balticus), silverweed (Potentilla anserina), harebell (Campanula rotundifolia), smooth aster (Symphyotrichum laeve), common water horehound (Lycopus americanus), northern bog violet (Viola nephrophylla), grass-leaved goldenrod (Euthamia graminifolia), and Kalm’s St. John’s-wort (Hypericum kalmianum). Other characteristic plants include panic grass (Dichanthelium lindheimeri), hair grass (Avenella flexuosa), balsam ragwort (Packera paupercula), Ohio goldenrod (Solidago ohioensis), golden-seeded spike-rush (Eleocharis elliptica), dwarf Canadian primrose (Primula mistassinica), sedges (Carex viridula and C. eburnea), and white camas (Anticlea elegans). The following trees and shrubs are commonly observed: northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis), paper birch (Betula papyrifera), white spruce (Picea glauca), balsam poplar (Populus balsamifera), shrubby cinquefoil (Dasiphora fruticosa), soapberry (Shepherdia canadensis), common juniper (Juniperus communis), and bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi).

Limestone bedrock lakeshores are characterized by a zonal gradation of plant communities, changing in response to distance from the lake. The width of the zones varies with Great Lakes water level fluctuations. Wave action and ice scour have their greatest impact closest to the lake. The “splash/scrape zone,” which averages 9 m (30 ft) in width, is very sparsely vegetated. Typical plant species include Baltic rush, silverweed, and balsam poplar. These species get established in cracks where there is some protection from severe ice scour and storm events. Throughout this zone, small pools of standing water are common on the bedrock. Inland from the splash/scrape zone, vegetation density increases as soil accumulates in and around cracks. The “vegetated zone,” which averages 25 m (75 ft) in width, is characterized by patchy establishment of vegetation interspersed with areas of exposed bedrock. Common species include low calamint, shrubby cinquefoil, panic grass, and hair grass, as well as the previously mentioned species from the splash/scrape zone. Farther inland, sand accumulations or “cobble ridges” on the bedrock surface afford a suitable substrate for the establishment of woody plants and denser assemblages of herbaceous plants. Cobble ridges are dominated by scattered shrubs and stunted trees including northern white-cedar, white spruce, and balsam poplar.

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Graminoids

- ticklegrass (Agrostis scabra)

- wavy hair grass (Avenella flexuosa)

- narrow-leaved reedgrass (Calamagrostis stricta)

- beauty sedge (Carex concinna)

- Crawe’s sedge (Carex crawei)

- ebony sedge (Carex eburnea)

- sedge (Carex garberi)

- Richardson’s sedge (Carex richardsonii)

- bulrush sedge (Carex scirpoidea)

- little green sedge (Carex viridula)

- poverty grass (Danthonia spicata)

- tufted hair grass (Deschampsia cespitosa)

- Lindheimer panic grass (Dichanthelium lindheimeri)

- golden-seeded spike-rush (Eleocharis elliptica)

- slender wheat grass (Elymus trachycaulus)

- Baltic rush (Juncus balticus)

- beak-rush (Rhynchospora capillacea)

Forbs

- purple false foxglove (Agalinis purpurea)

- white camas (Anticlea elegans)

- wild columbine (Aquilegia canadensis)

- harebell (Campanula rotundifolia)

- Indian paintbrush (Castilleja coccinea)

- limestone calamint (Clinopodium arkansanum)

- large yellow lady-slipper (Cypripedium parviflorum var. pubescens)

- flat-topped white aster (Doellingeria umbellata)

- large-leaved aster (Eurybia macrophylla)

- grass-leaved goldenrod (Euthamia graminifolia)

- wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana)

- dwarf lake iris (Iris lacustris )

- Kalm’s lobelia (Lobelia kalmii)

- common water horehound (Lycopus americanus)

- balsam ragwort (Packera paupercula)

- silverweed (Potentilla anserina)

- bird’s-eye primrose (Primula mistassinica)

- Houghton’s goldenrod (Solidago houghtonii )

- Ohio goldenrod (Solidago ohioensis)

- nodding ladies’-tresses (Spiranthes cernua)

- smooth aster (Symphyotrichum laeve)

- false asphodel (Triantha glutinosa)

- northern bog violet (Viola nephrophylla)

Shrubs

- bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi)

- shrubby cinquefoil (Dasiphora fruticosa)

- Kalm’s St. John’s-wort (Hypericum kalmianum)

- common juniper (Juniperus communis)

- ninebark (Physocarpus opulifolius)

- soapberry (Shepherdia canadensis)

Trees

- balsam fir (Abies balsamea)

- paper birch (Betula papyrifera)

- white spruce (Picea glauca)

- balsam poplar (Populus balsamifera)

- northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis)

Noteworthy Animals

Limestone bedrock lakeshore provides stopover and feeding corridors for migratory songbirds, including many warbler species.

Rare Plants

- Carex concinna (beauty sedge, state special concern)

- Carex richardsonii (Richardson’s sedge, state special concern)

- Carex scirpoidea (bulrush sedge, state threatened)

- Cirsium hillii (Hill's thistle, state special concern)

- Eleocharis compressa (flattened spike-rush, state threatened)

- Iris lacustris (dwarf lake iris, federal/state threatened)

- Pinguicula vulgaris (butterwort, state special concern)

- Piperia unalascensis (Alaska orchid, state special concern)

- Solidago houghtonii (Houghton's goldenrod, federal/state threatened)

Rare Animals

- Catinella exile (land snail, state special concern)

- Flexamia delongi (leafhopper, state special concern)

- Lanius ludovicianus migrans (loggerhead shrike, state endangered)

- Vertigo elatior (tapered vertigo, state special concern)

- Vertigo hubrichti (Hubricht’s vertigo, state special concern)

- Vertigo morsei (six-whorled vertigo, state special concern)

Biodiversity Management Considerations

Trampling of vegetation and off-road vehicle traffic use can kill or reduce vegetation coverage, destroying the root systems that bind small accumulations of soil to cracks in the bedrock. The removal of lakeshore vegetation facilitates the loss of soil by wind, rain, ice, or wave action, which is especially damaging in this erosive landscape where soil development and plant reestablishment are slow. Eliminating illegal off-road vehicle activity is a primary means of protecting the ecological integrity of limestone bedrock lakeshore and associated shoreline communities.

Invasive plant species that threaten the diversity and community structure of limestone bedrock lakeshore include spotted knapweed (Centaurea stoebe), mossy stonecrop (Sedum acre), ox-eye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare), common St. John’s-wort (Hypericum perforatum), Canada bluegrass (Poa compressa), Kentucky bluegrass (P. pratensis), hawkweeds (Hieracium spp.), sheep sorrel (Rumex acetosella), garden tansy (Tanacetum vulgare), common mullein (Verbascum thapsus), and glossy buckthorn (Frangula alnus). In addition, empty shells of zebra mussels (Dreissena polymorpha), a small invasive bivalve mussel, form deep piles on limestone bedrock pavement and locally limit vegetation establishment and impact soil accumulation, deposition, and erosion. Maintaining a mature, unfragmented forested buffer around limestone bedrock lakeshores may help limit the local seed source for invasive species distributed by wind or birds. Monitoring and control efforts to detect and remove these and other invasive species will help maintain the native biodiversity of limestone bedrock lakeshore and surrounding natural communities.

Variation

The composition of the limestone bedrock lakeshore is quite variable and may include areas of sand, silt, or clay minerals, which alter the rock’s resistance to erosion, influence the formation of crevices, and affect hydrologic conditions of the community.

Similar Natural Communities

Limestone cobble shore, limestone bedrock glade (alvar glade), alvar (alvar grassland), sandstone bedrock lakeshore, volcanic bedrock lakeshore, and granite bedrock lakeshore.

Places to Visit

- Drummond Island (Bass Cove, Huron Bay, Grand Marais Lake, and Seaman's Point), Sault Sainte Marie State Forest Management Unit, Chippewa Co.

- Fisherman's Island, Fisherman's Island State Park, Charlevoix Co.

- Point De Tour, Shingleton State Forest Management Unit, Delta Co.

Relevant Literature

- Albert, D.A., P. Comer, D. Cuthrell, D. Hyde, W. MacKinnon, M. Penskar, and M. Rabe. 1997. The Great Lakes bedrock lakeshores of Michigan. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 218 pp.

- Belcher, J.W., P.A. Keddy, and P.A. Catling. 1992. Alvar vegetation in Canada: A multivariate description at two scales. Canadian Journal of Botany 70: 1279-1291.

- Brownell, V.R, and J.L. Riley. 2000. The alvars of Ontario: Significant alvar natural areas in the Ontario Great Lakes region. Federation of Ontario Naturalists, Don Mills, ON. 269 pp.

- Catling, P.M. 1995. The extent of confinement of vascular plants to alvars in southern Ontario. Canadian Field Naturalist 109: 172-181.

- Catling, P.M., and V.R. Browell. 1995. A review of alvars of the Great Lakes region: Distribution, floristic composition, biogeography, and protection. Canadian Field Naturalist 109: 143-171.

- Catling, P.M., and V.R. Brownell. 1999. Alvars of the Great Lakes region. Pp. 375-391 in Savannas, barrens, and rock outcrop plant communities of North America, ed. R.C. Anderson, J.S. Fralish, and J.M. Baskin. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 480 pp.

- Comer, P.J., D.L. Cuthrell, D.A. Albert. 1997. Natural community abstract for limestone bedrock lakeshore. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 3 pp.

- Dorr, J.A., Jr., and D.F. Eschman. 1970. Geology of Michigan. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI. 470 pp.

- Ehlers, G.M. 1973. Stratigraphy of the Niagran Series of the Northern Peninsula of Michigan. University of Michigan Museum of Paleontology, Papers on Paleontology no. 3. 200 pp.

- Faber-Langendoen, D., ed. 2001. Plant communities of the Midwest: Classification in an ecological context. Association for Biodiversity Information, Arlington, VA. 61 pp. + appendix (705 pp.).

- Reed, R.C., and J. Daniels. 1987. Bedrock geology of northern Michigan. State of Michigan Department of Natural Resources. Map: 1: 500,000.

- Reschke, C., R. Reid, J. Jones, T. Feeney, and H. Potter. 1999. Conserving Great Lakes alvar: Final technical report of the International Alvar Conservation Initiative. The Nature Conservancy, Chicago, IL. 241 pp.

- Schaefer, C.A., and D.W. Larson. 1997. Vegetation, environmental characteristics, and ideas on the maintenance of alvars on the Bruce Peninsula, Canada. Journal of Vegetation Science 8: 797-810.

- Stephenson, S.N., and P.S. Herendeen. 1986. Short-term drought effects on the alvar communities of Drummond Island, Michigan. Michigan Botanist 25: 16-27.

For a full list of references used to create this description, please refer to the natural community abstract for Limestone Bedrock Lakeshore.

More Information

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: March 7, 2026).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.