Northern Shrub Thicket

Overview

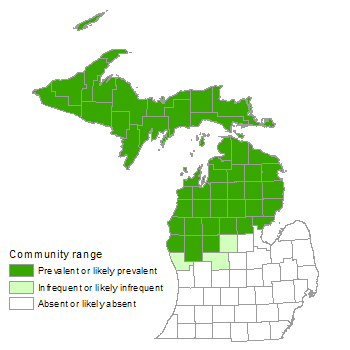

Northern shrub thicket is a shrub-dominated wetland located north of the climatic tension zone, typically occurring along streams, but also adjacent to lakes and beaver floodings. The saturated, nutrient-rich, organic soils are composed of sapric peat or less frequently mineral soil, typically with medium acid to neutral pH. Succession to closed-canopy swamp forest is slowed by fluctuating water tables, beaver flooding, and windthrow. Northern shrub thickets are overwhelmingly dominated by tag alder (Alnus incana).

Rank

Global Rank: G4 - Apparently secure

State Rank: S5

Landscape Context

Northern shrub thicket occurs principally along streams, beaver floodings, lakeshores, and rivers within glacial outwash channels and less frequently within ice-contact topography and coarse-textured end moraines. Sites are characterized by little to no slope, can range from small pockets to extensive acreages, and are often a narrow band or zone of 20 to 30 meters within a larger wetland complex. The community typically grades into northern wet meadow along stream and lake margins, and along the margins of uplands it often borders swamp forest.

Soils

The soils of northern shrub thicket are wet to moist, nutrient-rich, well-decomposed sapric peat, or occasionally mineral soil. The pH ranges widely from alkaline to acidic with medium acidity being the most prevalent condition. The soils are characterized by high nutrient levels due to the nitrogen-fixing ability of alder. Northern shrub thickets are non-stagnant wetlands with high levels of dissolved oxygen and soil nitrogen. Soils range from poorly drained to well drained, with most sites remaining saturated throughout the growing season. The community is typically flooded in spring.

Natural Processes

Northern shrub thickets can become established following severe disturbance of swamp forests or through shrub establishment in open wetlands such as northern wet meadow. Flooding (i.e., from beaver or fluvial processes), fire, disease, and windthrow can result in sufficient mortality of the swamp forest overstory to allow for the complete opening of the forest canopy and the expansion of alder through establishment of seedlings or stump sprouting. Following canopy release, alder can form dense, impenetrable thickets that retard or prevent tree establishment. Within open wetlands, alder and associated shrubs can become established following alteration in the fire or hydrologic regime. Prolonged periods without fire, an absence of beaver flooding, or the lowering of the water table allows for shrub encroachment into open wetlands and conversion to northern shrub thicket. Once established, northern shrub thicket can persist if disturbance factors prevent tree establishment and growth. Windthrow, beaver herbivory, beaver flooding, seasonal flooding, and fire can all limit tree establishment and survival. Alder’s capacity to stump-sprout following flooding, fire, and herbivory allow it to persist after these disturbances. However, long-term flooding as a result of beaver damming can eliminate alder as well as other woody species. Northern shrub thicket typically succeeds to closed-canopy swamp forest in the absence of disturbance factors that prevent tree establishment and survival or cause prolonged flooding.

Vegetation

Northern shrub thickets are characterized by an overwhelming dominance of tag alder, which forms dense, often monotypic thickets with canopy coverage ranging between 40 and 95% and stand height typically ranging from one to three meters. The community exhibits a high degree of floristic homogeneity due to the dominance of alder. Floristic diversity is usually correlated with the degree of shrub canopy closure, with higher levels of diversity occurring in more open sites. The understory, which is comprised of species from both meadow and forest, is dominated by an array of short shrubs, forbs, grasses, sedges, and ferns. Prevalent herbs of northern shrub thickets include: marsh marigold (Caltha palustris), marsh bellflower (Campanula aparinoides), marsh cinquefoil (Comarum palustre), joe-pye-weed (Eutrochium maculatum), common boneset (Eupatorium perfoliatum), rough bedstraw (Galium asprellum), jewelweed (Impatiens capensis), wild blue flag (Iris versicolor), northern bugleweed (Lycopus uniflorus), wild mint (Mentha canadensis), monkey-flower (Mimulus ringens), golden ragwort (Packera aurea), common skullcap (Scutellaria galericulata), mad-dog skullcap (S. lateriflora), Canada goldenrod (Solidago canadensis), late goldenrod (S. gigantea), rough goldenrod (S. rugosa), swamp aster (Symphyotrichum puniceum), skunk cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus), and purple meadow rue (Thalictrum dasycarpum). Characteristic ferns and fern allies include common horsetail (Equisetum arvense), sensitive fern (Onoclea sensibilis), cinnamon fern (Osmunda cinnamomea), royal fern (O. regalis), and marsh fern (Thelypteris palustris). Short shrubs include sweet gale (Myrica gale), wild black currant (Ribes americanum), swamp dewberry (Rubus hispidus), dwarf raspberry (R. pubescens), wild red raspberry (R. strigosus), and meadowsweet. Where alder does not form a monospecific shrub layer, associates of the tall shrub layer can include black chokeberry (Aronia prunifolia), bog birch (Betula pumila), silky dogwood (Cornus amomum), red-osier dogwood (C. sericea), winterberry (Ilex verticillata), Bebb’s willow (Salix bebbiana), pussy willow (S. discolor), sandbar willow (S. exigua), slender willow (S. petiolaris), wild-raisin (Viburnum cassinoides), and American highbush-cranberry (V. trilobum). Scattered trees and tree saplings are often found invading northern shrub thickets. Typical tree species include balsam fir (Abies balsamea), red maple (Acer rubrum), black ash (Fraxinus nigra), tamarack (Larix laricina), black spruce (Picea mariana), balsam poplar (Populus balsamifera), quaking aspen (P. tremuloides), and northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis).

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Graminoids

- blue-joint (Calamagrostis canadensis)

- lake sedge (Carex lacustris)

- retrorse sedge (Carex retrorsa)

- tussock sedge (Carex stricta)

- rattlesnake grass (Glyceria canadensis)

- fowl manna grass (Glyceria striata)

- cut grass (Leersia oryzoides)

- fowl meadow grass (Poa palustris)

- green bulrush (Scirpus atrovirens)

Forbs

- marsh-marigold (Caltha palustris)

- marsh bellflower (Campanula aparinoides)

- marsh cinquefoil (Comarum palustre)

- common boneset (Eupatorium perfoliatum)

- joe-pye-weed (Eutrochium maculatum)

- rough bedstraw (Galium asprellum)

- jewelweed (Impatiens capensis)

- wild blue flag (Iris versicolor)

- northern bugle weed (Lycopus uniflorus)

- wild mint (Mentha canadensis)

- monkey-flower (Mimulus ringens)

- golden ragwort (Packera aurea)

- great water dock (Rumex orbiculatus)

- common skullcap (Scutellaria galericulata)

- mad-dog skullcap (Scutellaria lateriflora)

- Canada goldenrod (Solidago canadensis)

- late goldenrod (Solidago gigantea)

- rough goldenrod (Solidago rugosa)

- panicled aster (Symphyotrichum lanceolatum)

- swamp aster (Symphyotrichum puniceum)

- skunk-cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus)

- purple meadow-rue (Thalictrum dasycarpum)

Ferns

- sensitive fern (Onoclea sensibilis)

- cinnamon fern (Osmunda cinnamomea)

- royal fern (Osmunda regalis)

- marsh fern (Thelypteris palustris)

Fern Allies

- common horsetail (Equisetum arvense)

Shrubs

- tag alder (Alnus incana)

- black chokeberry (Aronia prunifolia)

- bog birch (Betula pumila)

- silky dogwood (Cornus amomum)

- red-osier dogwood (Cornus sericea)

- winterberry (Ilex verticillata)

- sweet gale (Myrica gale)

- wild black currant (Ribes americanum)

- swamp rose (Rosa palustris)

- swamp dewberry (Rubus hispidus)

- dwarf raspberry (Rubus pubescens)

- wild red raspberry (Rubus strigosus)

- willows (Salix bebbiana, S. discolor, S. exigua, S. petiolaris)

- meadowsweet (Spiraea alba)

- wild-raisin (Viburnum cassinoides)

- American highbush-cranberry (Viburnum trilobum)

Trees

- balsam fir (Abies balsamea)

- red maple (Acer rubrum)

- black ash (Fraxinus nigra)

- tamarack (Larix laricina)

- black spruce (Picea mariana)

- white pine (Pinus strobus)

- northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis)

Noteworthy Animals

The leaves and twigs of alder provide important food resources for a wide array of mammals including moose (Alces alces, state threatened), muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus), beaver (Castor canadensis), cottontail rabbit (Sylvilagus floridanus), and snowshoe hare (Lepus americanus). Beaver build dams and lodges with tag alder twigs. In addition, beaver activity can strongly influence establishment, maintenance, expansion, and conversion of northern shrub thicket. The buds and seeds of alder are eaten by a diversity of birds. Songbirds feed on alder seeds, and American woodcock (Philohela minor) and ruffed grouse (Bonasa umbellus) eat the buds and catkins. Thickets of alder provide important cover for species such as white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), river otter (Lutra canadensis), and mink (Mustela vison). Gray wolf (Canis lupus, federal/state threatened) and lynx (Lynx canadensis, state endangered) also utilize shrub thicket habitat.

Rare Plants

- Equisetum telmateia (giant horsetail, presumed extirpated from Michigan)

- Listera auriculata (auricled twayblade, state special concern)

- Lonicera involucrata (black twinberry, state threatened)

- Mimulus guttatus (western monkey-flower, state special concern)

- Stellaria crassifolia (fleshy stitchwort, state threatened)

- Thalictrum venulosum var. confine (veiny meadow-rue, state special concern)

Rare Animals

- Alces alces (moose, state threatened)

- Ardea herodias (great blue heron, protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918)

- Canis lupus (gray wolf, state threatened)

- Emydoidea blandingii (Blanding’s turtle, state special concern)

- Glyptemys insculpta (wood turtle, state special concern)

- Haliaeetus leucocephalus (bald eagle, state threatened)

- Lynx canadensis (lynx, state endangered)

- Oncocnemis piffardi (three-striped oncocnemis, state special concern)

- Pandion haliaetus (osprey, state threatened)

- Pseudacris triseriata maculata (boreal chorus frog, state special concern)

- Sistrurus c. catenatus (eastern massasauga, federal candidate species and state special concern)

Biodiversity Management Considerations

In the Great Lakes region, northern shrub thicket is a widespread community type that has dramatically increased in acreage from its historical extent due to anthropogenic disturbance. The increase in northern shrub thicket is the result of extensive logging of swamp forests, alteration of hydrologic regimes, and fire suppression. Turn-of-the-century logging of conifer swamp resulted in the conversion of many forested swamps to northern shrub thicket in the Great Lakes region. In areas historically dominated by open, herbaceous wetlands (i.e., northern wet meadow, northern fen, emergent marsh), tiling, ditching, and road building have lowered the water table, resulting in their conversion to shrub-dominated wetlands. As the result of fire suppression and low beaver populations, many open wetlands have converted to shrub-dominated wetlands. Northern shrub thicket has also been maintained and expanded by wildlife management geared toward providing favorable habitat for game species of early-successional habitat, particularly white-tailed deer, American woodcock, and ruffed grouse.

Alder swamps contribute significantly to the overall biodiversity of northern Michigan by providing habitat to a wide variety of plant and animal species including several rare species. However, northern shrub thickets have replaced many rare and declining wetland communities such as rich conifer swamp and northern fen. Where shrub encroachment threatens to convert less common open wetlands to shrub-dominated systems, prolonged flooding, repeated prescribed fires, mowing, or herbicide application to cut shrub stumps can be employed to maintain open conditions. On sites in which northern shrub thicket is succeeding to swamp forest, allowing succession to proceed unhindered will result in increased acreage of less common swamp communities. Northern shrub thicket can be maintained by cutting overstory trees and where feasible, mild intensity burning can be used to encourage alder regeneration. While northern shrub thicket has replaced many declining and rare communities, it does provide important ecosystem services, protecting water quality by assimilating nutrients, trapping sediment, and retaining stormwater and floodwater.

Monitoring and control efforts to detect and remove invasive species are critical to the long-term viability of northern shrub thicket and associated wetlands. Particularly aggressive invasive species that threaten the diversity and community structure include glossy buckthorn (Frangula alnus), multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora), purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), narrow-leaved cat-tail (Typha angustifolia), hybrid cat-tail (Typha xglauca), reed canary grass (Phalaris arundinacea), and reed (Phragmites australis subsp. australis).

Variation

Community size, shape, and species composition can vary significantly, depending on landscape context. Generally, occurrences on poorly drained, level outwash plains and lakeplains are larger than those associated with narrow outwash channels and stream corridors.

Similar Natural Communities

Floodplain forest, Great Lakes marsh, hardwood-conifer swamp, inundated shrub swamp, northern fen, northern hardwood swamp, northern wet meadow, poor conifer swamp, rich conifer swamp, southern shrub-carr, and wooded dune and swale complex.

Places to Visit

- Au Sable River, Hartwick Pines State Park, Crawford Co.

- Carp River, Porcupine Mountains Wilderness State Park, Ontonagon Co.

- Laughing Whitefish River, Laughing Whitefish Falls State Park, Alger Co.

- Little Two-Hearted River, Tahquamenon Falls State Park, Luce Co.

Relevant Literature

- Cohen, J.G. 2005. Natural community abstract for northern shrub thicket. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 8 pp.

- Eggers, S.D., and D.M. Reed. 1997. Wetland plants and plant communities of Minnesota and Wisconsin. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, St. Paul, MN. 263 pp.

- Huenneke, L.F., and P.L. Marks. 1987. Stem dynamics of the shrub Alnus incana ssp. rugosa: Transition matrix model. Ecology 68(5): 1234-1242.

- Ohmann, L.F., M.D. Knighton, and R. McRoberts. 1990. Influence of flooding duration on the biomass growth of alder and willow. Research Paper NC-292. USDA, Forest Service, North Central Forest Experiment Station, St. Paul, MN. 5 pp.

- Parker, G.R., and G. Schneider. 1974. Structure and edaphic factors of an alder swamp in northern Michigan. Canadian Journal of Forestry Research 4: 499-508.

- Van Deelen, T.R. 1991. Alnus rugosa. In Fire Effects Information System [online]. USDA, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ (Accessed: May 20, 2004.)

For a full list of references used to create this description, please refer to the natural community abstract for Northern Shrub Thicket.

More Information

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: February 2, 2026).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.