Hardwood-Conifer Swamp

Overview

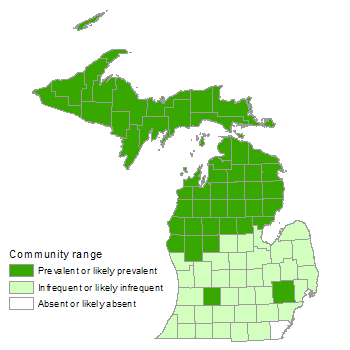

Hardwood-conifer swamp is a minerotrophic forested wetland dominated by a mixture of lowland hardwoods and conifers, occurring on organic (i.e., peat) and poorly drained mineral soils throughout Michigan. The community occurs on a variety of landforms, often associated with headwater streams and areas of groundwater discharge. Species composition and dominance patterns can vary regionally. Windthrow and fluctuating water levels are the primary natural disturbances that structure hardwood-conifer swamp.

Rank

Global Rank: G4 - Apparently secure

State Rank: S3 - Vulnerable

Landscape Context

Hardwood-conifer swamp is typically associated with headwater streams or shallow kettle depressions in poorly drained outwash channels or in depressions on outwash plains, medium- to coarse-textured end moraines, and glacial lakeplains. Shallow kettle depressions and the margins of large forested and non-forested peatlands may also support hardwood-conifer swamp, but the community is absent from areas where significant peat accumulation isolates the rooting zone from contact with mineral-rich groundwater. Occurrences of hardwood-conifer swamp are often narrow (typically <500 m wide), following slope contours.500 m wide), following slope contours.

Soils

Substrate conditions are heterogeneous, and are often highly variable within a single stand. The most common condition is a thin layer of organic soil over a poorly drained mineral substrate. Organic soils are typically saturated, highly decomposed, sapric peat (i.e., muck) and frequently contain pieces of coarse wood throughout their soil profiles. Areas of deep (>1 m) organic deposition are common, especially in seeps. Substrate pH is also highly variable. Saturated mucks are typically of neutral pH, but may be acidic near the surface, especially where associated with sphagnum mosses or where coniferous needle mats accumulate. Mineral soils are often acidic. Vegetation (living and dead), depth to the water table, and groundwater movement all influence substrate alkalinity.

Natural Processes

The primary natural processes structuring hardwood-conifer swamp are windthrow and dynamics of surface water and groundwater. Patchy windthrow creates small-scale canopy gaps and complex microtopography, which influence ground layer diversity. Accumulation of ice and snow in tree crowns increases the likelihood of windthrow or trunk snap, particularly for trees weakened by pests or fungal pathogens. The creation of canopy gaps and associated microtopographic heterogeneity has important consequences for the establishment and recruitment of canopy trees. Seedlings of several characteristic hardwood-conifer swamp canopy tree species (e.g., yellow birch, white pine, northern white-cedar, and hemlock) preferentially germinate and establish on hummocks and/or decaying logs versus muck or litter-covered hollows. In comparison to hollows, hummocks and decaying logs have high moss cover, high moisture content, coarse substrate texture, and stable hydrology, characteristics that favor the germination and establishment of small seeds with low nutrient reserves.

Significant hydrological processes impacting hardwood-conifer swamp include groundwater seepage, water table fluctuation, seasonal inundation, and flooding events (often associated with beaver activity). Plant species composition is influenced by groundwater seepage rich in calcium and magnesium carbonates. Water table fluctuations interact with canopy gap size, such that mid- and large-sized gaps may flood quickly during rain events, presumably due to the lack of canopy to intercept precipitation, in addition to the lack of transpiration by large trees. These wet gaps create microheterogeneity that results in increased diversity of vascular plant species, including many species otherwise characteristic of open wetland types.

The relative contribution of fire to hardwood-conifer swamp structure and succession is unknown, but fire does create suitable conditions for the establishment of new cohorts of several canopy dominants. Return intervals for destructive crown fires in conifer-dominated swamps have been estimated at up to 3,000 years in north-central Lower Michigan. However, less severe surface fires may occur with greater frequency.

Vegetation

Species composition within hardwood-conifer swamps exhibits considerable variation across the state. Canopy closure varies, depending on substrate characteristics and the disturbance history of each individual site. In southern Lower Michigan, canopy dominance is often by red maple (Acer rubrum) and black ash (Fraxinus nigra), with yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis) and white pine (Pinus strobus) common canopy associates. Additional canopy species may include American elm (Ulmus americana), basswood (Tilia americana), northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis), hemlock (Tsuga canadensis), tamarack (Larix laricina), and, locally, tulip tree (Liriodendron tulipifera). In northern Michigan, canopy dominance is often by hemlock, and associates may include yellow birch, red maple, black ash, basswood, American elm, balsam poplar (Populus balsamifera), white pine, northern white-cedar, tamarack, balsam fir (Abies balsamea), white spruce (Picea glauca), and black spruce (P. mariana). Geographic variants occurring primarily north of the tension zone include stands that are dominated almost exclusively by hemlock and in the western Upper Peninsula by hemlock and yellow birch.

Small trees and tall shrubs form an open to closed subcanopy, depending on canopy closure. This layer is characterized by saplings of canopy species, in addition to mountain maple (Acer spicatum), tag alder (Alnus incana), paper birch (Betula papyrifera), musclewood (Carpinus caroliniana), red-osier dogwood (Cornus sericea), gray dogwood (C. foemina), winterberry (Ilex verticillata), poison sumac (Toxicodendron vernix), and spicebush (Lindera benzoin). Characteristic low shrubs include American fly honeysuckle (Lonicera canadensis) and alder-leaved buckthorn (Rhamnus alnifolia). Historically, Canadian yew (Taxus canadensis) was a prevalent shrub in hardwood-conifer swamp, but has since been reduced or locally extirpated from most sites by heavy deer herbivory.

The ground layer ranges from sparse under the shade of conifers to dense in light gaps and openings, and is characterized by the development of moss- and litter-covered hummocks and saturated, often inundated hollows on exposed muck soils. Characteristic species of hummocks and decomposing wood include wild sarsaparilla (Aralia nudicaulis), small enchanter’s nightshade (Circaea alpina), bluebead lily (Clintonia borealis), goldthread (Coptis trifolia), bunchberry (Cornus canadensis), woodfern (Dryopteris spp.), oak fern (Gymnocarpium dryopteris), Canada mayflower (Maianthemum canadense), partridge berry (Mitchella repens), naked miterwort (Mitella nuda), dwarf raspberry (Rubus pubescens), and starflower (Trientalis borealis). Typical species of hollows and open, mucky flats include jack-in-the-pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum), beggar-ticks (Bidens spp.), sedges (including Carex intumescens, C. crinita, C. disperma, C. gracillima, C. hystericina, C. lacustris, C. stricta, C. bromoides, and others), fowl manna grass (Glyceria striata), jewelweed (Impatiens capensis), northern bugle weed (Lycopus uniflorus), sensitive fern (Onoclea sensibilis), cinnamon fern (Osmunda cinnamomea), royal fern (O. regalis), golden ragwort (Packera aurea), rough goldenrod (Solidago rugosa), and skunk cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus).

Vines are often conspicuous in hardwood-conifer swamps, particularly in canopy gaps and along streams. Characteristic species include hog-peanut (Amphicarpaea bracteata), groundnut (Apios americana), virgin’s bower (Clematis virginiana), wild yam (Dioscorea villosa), honeysuckles (primarily Lonicera dioica), Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia), poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), and riverbank grape (Vitis riparia).

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Graminoids

- sedges (Carex bromoides, C. crinita, C. disperma, C. folliculata, C. gracillima, C. hystericina, C. intumescens, C. lacustris, C. lupulina, C. stricta, and others)

- wood reedgrasses (Cinna arundinacea and C. latifolia)

- Virginia wild-rye (Elymus virginicus)

- fowl manna grass (Glyceria striata)

- rice cut grass (Leersia oryzoides)

- bog bluegrass (Poa paludigena)

- fowl meadow grass (Poa palustris)

Forbs

- wild sarsaparilla (Aralia nudicaulis)

- jack-in-the-pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum)

- beggar-ticks (Bidens spp.)

- marsh-marigold (Caltha palustris)

- spring cress (Cardamine bulbosa)

- Pennsylvania bitter cress (Cardamine pensylvanica)

- cuckoo-flower (Cardamine pratensis)

- turtlehead (Chelone glabra)

- golden saxifrage (Chrysosplenium americanum)

- small enchanter’s-nightshade (Circaea alpina)

- virgin’s bower (Clematis virginiana)

- bluebead lily (Clintonia borealis)

- goldthread (Coptis trifolia)

- lady-slippers (Cypripedium spp.)

- flat-topped white aster (Doellingeria umbellata)

- willow-herbs (Epilobium spp.)

- jewelweed (Impatiens capensis)

- twinflower (Linnaea borealis)

- northern bugle weed (Lycopus uniflorus)

- tufted loosestrife (Lysimachia thyrsiflora)

- Canada mayflower (Maianthemum canadense)

- partridge berry (Mitchella repens)

- bishop’s-cap (Mitella diphylla)

- naked miterwort (Mitella nuda)

- northern wood sorrel (Oxalis acetosella)

- golden ragwort (Packera aurea)

- smartweeds (Persicaria spp.)

- gay-wings (Polygala paucifolia)

- water-parsnip (Sium suave)

- goldenrods (Solidago patula, S. rugosa, and others)

- calico aster (Symphyotrichum lateriflorum)

- swamp aster (Symphyotrichum puniceum)

- skunk-cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus)

- starflower (Trientalis borealis)

- violets (Viola spp.)

Ferns

- wood ferns (Dryopteris spp.)

- oak fern (Gymnocarpium dryopteris)

- sensitive fern (Onoclea sensibilis)

- cinnamon fern (Osmunda cinnamomea)

- interrupted fern (Osmunda claytoniana)

- royal fern (Osmunda regalis)

- New York fern (Thelypteris noveboracensis)

Fern Allies

- horsetails (Equisetum spp.)

Woody Vines

- red honeysuckle (Lonicera dioica)

- Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia)

- poison-ivy (Toxicodendron radicans)

- riverbank grape (Vitis riparia)

Mosses

- callicladium moss (Callicladium haldanianum)

- big red stem moss (Pleurozium schreberi)

- sphagnum mosses (Sphagnum spp.)

Shrubs

- tag alder (Alnus incana)

- bunchberry (Cornus canadensis)

- dogwoods (Cornus foemina and C. sericea)

- creeping snowberry (Gaultheria hispidula)

- winterberry (Ilex verticillata)

- spicebush (Lindera benzoin)

- Canadian fly honeysuckle (Lonicera canadensis)

- alder-leaved buckthorn (Rhamnus alnifolia)

- swamp red currant (Ribes triste)

- dwarf raspberry (Rubus pubescens)

- poison sumac (Toxicodendron vernix)

Trees

- balsam fir (Abies balsamea)

- red maple (Acer rubrum)

- mountain maple (Acer spicatum)

- yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis)

- paper birch (Betula papyrifera)

- musclewood (Carpinus caroliniana)

- black ash (Fraxinus nigra)

- green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica)

- tamarack (Larix laricina)

- white spruce (Picea glauca)

- black spruce (Picea mariana)

- white pine (Pinus strobus)

- northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis)

- basswood (Tilia americana)

- hemlock (Tsuga canadensis)

- American elm (Ulmus americana)

Noteworthy Animals

Through flooding and herbivory, beaver can cause tree mortality and the conversion to open wetlands such as shallow ponds, emergent marsh, wet meadows, shrub swamps, or fens. Insect outbreaks and plant parasites can set back or kill conifers, altering community composition and structure. The larch sawfly (Pristophora erichsonii), larch casebearer (Coleophora laricella), and spruce budworm (Choristoneura fumiferana) can repeatedly defoliate and kill tamarack. Spruce budworm also defoliates both black spruce and balsam fir but tends to be more detrimental to the latter. The plant parasite dwarf mistletoe (Arceuthobium pusillum) can increase the mortality of black spruce.

Rare Plants

- Berula erecta (cut-leaved water-parsnip, state threatened)

- Carex seorsa (sedge, state threatened)

- Dentaria maxima (large toothwort, state threatened)

- Hydrastis canadensis (goldenseal, state threatened)

- Lonicera involucrata (black twinberry, state threatened)

- Mimulus glabratus var. michiganensis (Michigan monkey-flower, federal/state endangered)

- Poa paludigena (bog bluegrass, state threatened)

- Trillium undulatum (painted trillium, state endangered)

Rare Animals

- Accipiter cooperii (Cooper’s hawk, state special concern)

- Accipiter gentilis (northern goshawk, state special concern)

- Alces alces (moose, state special concern)

- Appalachina sayanus (spike-lip crater, state special concern)

- Ardea herodias (great blue heron, protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918)

- Asio otus (long-eared owl, state threatened)

- Buteo lineatus (red-shouldered hawk, state threatened)

- Canis lupus (gray wolf, state threatened)

- Emydoidea blandingii (Blanding’s turtle, state special concern)

- Glyptemys insculpta (wood turtle, state special concern)

- Gomphus quadricolor (rapids clubtail, state special concern)

- Haliaeetus leucocephalus (bald eagle, state threatened)

- Incisalia henrici (Henry’s elfin, state special concern)

- Pachypolia atricornis (three-horned moth, state special concern)

- Pandion haliaetus (osprey, state threatened)

- Papaipema speciosissima (regal fern borer, state special concern)

- Sistrurus c. catenatus (eastern massasauga, federal candidate species and state special concern)

- Tachopteryx thoreyi (grey petaltail, state special concern)

- Terrapene c. carolina (eastern box turtle, state special concern)

- Williamsonia fletcheri (ebony boghaunter, state special concern)

Biodiversity Management Considerations

Conservation and management of hardwood-conifer swamp should focus on the following key areas: maintenance of the coarse woody debris resource; protection of mature seed-bearing trees; maintenance of canopy gap structure; protection of groundwater and surface water hydrology; reduction of deer browse pressure; and control and monitoring of invasive species, including plants, animals, and pathogens.

Regeneration of hardwood-conifer swamp canopy trees, particularly of conifers, relies on the presence of suitable sites for germination and establishment within the stand. Management should focus on protecting decaying logs and hummocks that are favored germination sites for yellow birch, white pine, northern white-cedar, and hemlock. Maintaining mature, senescent, and dead canopy trees within hardwood-conifer swamp stands ensures a continuing source of the large-diameter coarse woody debris important for seedling germination and survival. Removal of coarse woody debris or senesced trees from hardwood-conifer swamps should be avoided or minimized to ensure the continued viability of the system.

Maintaining mature, seed-bearing conifer trees is important for ensuring the continued presence of seed sources within the wetland. Removal of mature conifers from hardwood-conifer swamps should be carefully considered to avoid converting the affected stands to hardwood dominance. Expansion of red maple in some stands, often following logging or hydrologic disturbance, limits conifer seedling establishment and recruitment by reducing light availability at the ground level.

Protection of groundwater and surface water hydrology is critical to maintaining the integrity of the hardwood-conifer swamp community. Hydrologic disturbances, including road construction and ditching, cause peat subsidence and decomposition and alter water tables by draining water or blocking its flow.

High deer density has lead to significant browse pressure on conifer seedlings and saplings and resulted in poor regeneration in much of the state. In addition, deer browse reduces frequency and cover of understory shrubs and herbs, altering structure of all strata and producing a cascade of effects extending to pollinators of affected plant species. Reduction of deer densities at the landscape-scale will promote recovery of tree seedling, shrub, and herb populations.

Invasive plant species that can reduce diversity and alter community structure of hardwood-conifer swamps include reed canary grass (Phalaris arundinacea), reed (Phragmites australis subsp. australis), purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata), and glossy buckthorn (Frangula alnus). Monitoring and control efforts to detect and remove these and other invasive species are important for protecting affected and surrounding natural communities. Pests of potential significant impact include the hemlock woolly adelgid (Adelges tsugae), which has the potential to cause significant hemlock mortality if it spreads throughout Michigan, and the emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis), which has already decimated ash populations in southeastern Lower Michigan.

Variation

There are several variants that share similar vegetative composition but exhibit different dominance patterns. In southern Lower Michigan, hardwoods, typically red maple, black ash, and yellow birch, dominate some stands, with a significant component of white pine and northern white-cedar. North of the tension zone, hemlock dominates some stands, sometimes to the near exclusion of other tree species. In the western Upper Peninsula, hemlock shares dominance with yellow birch in some stands. Elsewhere in northern Michigan, lowland hardwoods and boreal conifers exhibit mixed dominance patterns that require further study.

Similar Natural Communities

Rich conifer swamp, rich tamarack swamp, floodplain forest, northern hardwood swamp, southern hardwood swamp, and mesic northern forest.

Places to Visit

- Beavertown Lakes, Newberry State Forest Management Unit and The Nature Conservancy (Two-Hearted River Forest Preserve), Luce Co.

- Clinton River Headwaters, Independence Oaks County Park, Oakland County Parks, Oakland Co.

- Long Lake, Yankee Springs State Recreation Area, Barry Co.

- Mill Creek Swamp, Three Rivers State Game Area, Cass Co. and St. Joseph Co.

- Tahquamenon River, Tahquamenon Falls State Park, Chippewa Co. and Luce Co.

Relevant Literature

- Anderson, K.L., and D.J. Leopold. 2002. The role of canopy gaps in maintaining vascular plant diversity at a forested wetland in New York State. Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 129: 238-250.

- Comer, P.J., D.A. Albert, H.A. Wells, B.L. Hart, J.B. Raab, D.L. Price, D.M. Kashian, R.A. Corner, and D.W. Schuen. 1995. Michigan’s presettlement vegetation, as interpreted from the General Land Office Surveys 1816-1856. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. Digital map.

- Forrester, J.A., T.E. Yorks, and D.J. Leopold. 2005. Arboreal vegetation, coarse woody debris, and disturbance history of mature and old-growth stands in a coniferous forested wetland. Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 132: 252-261.

- NatureServe. 2006. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [Web application]. Version 6.1. NatureServe, Arlington, VA. Available http://www.natureserve.org/explorer. (Accessed: November 30, 2006.)

- Paratley, R.D., and T.J. Fahey. 1986. Vegetation - Environment relations in a conifer swamp in central New York. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 113: 357-371.

- Rooney, T.P., S.L. Solheim, and D.M. Waller. 2002. Factors affecting the regeneration of northern white cedar in lowland forests of the Upper Great Lakes region, USA. Forest Ecology and Management 163: 119-130.

- Schneider, G.J., and K.E. Cochrane. 1998. Plant community survey of the Lake Erie Drainage. Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Division of Natural Areas and Preserves, Columbus, OH.

- Slaughter, B.S., J.G. Cohen, and M.A. Kost. 2007. Natural community abstract for hardwood-conifer swamp. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 19 pp.

- Slaughter, B.S., and J.D. Skean, Jr. 2003. Comparison of cedar and tamarack stands in a relict conifer swamp at Pierce Cedar Creek Institute, Barry County, Michigan. Michigan Botanist 42: 111-126.

- Wenger, J.D. 1975. The vegetation of a white-cedar swamp in southwestern Michigan. Michigan Botanist 14: 124-130.

For a full list of references used to create this description, please refer to the natural community abstract for Hardwood-Conifer Swamp.

More Information

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: March 5, 2026).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.