Great Lakes Marsh

Overview

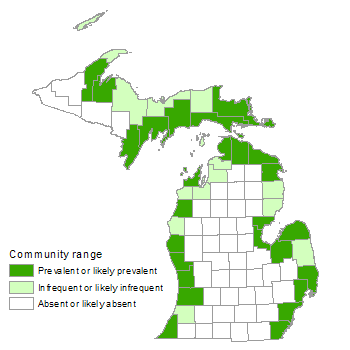

Great Lakes marsh is an herbaceous wetland community occurring statewide along the shoreline of the Great Lakes and their major connecting rivers. Vegetational patterns are strongly influenced by water level fluctuations and type of coastal feature, but generally include the following: a deep marsh with submerged plants; an emergent marsh of mostly narrow-leaved species; and a sedge-dominated wet meadow that is inundated by storms. Great Lakes marsh provides important habitat for migrating and breeding waterfowl, shore-birds, spawning fish, and medium-sized mammals.

Rank

Global Rank: G2 - Imperiled

State Rank: S3 - Vulnerable

Landscape Context

Great Lakes marshes occur along all of the Great Lakes and their connecting rivers, including the Detroit, St. Clair, and St. Mary’s Rivers. The physical and chemical characteristics of different surficial bedrock types affect wetland location and species composition. Igneous and metamorphic bedrocks form the shore of Lake Superior. Softer, sedimentary bedrock types underlie Lakes Michigan, Huron, St. Clair, Erie, and Ontario, as well as the large connecting rivers. Along Lake Superior, marshes occur only behind protective barrier beaches or at stream mouths. In contrast, the horizontally deposited marine and nearshore sedimentary rocks underlying Lakes Michigan, Huron, St. Clair, Erie, and Ontario provide broad zones of shallow water and fine-textured substrates for marsh development.

Great Lakes marshes occur in all three aquatic systems, including lacustrine, connecting channel, and riverine wetlands, which are defined by water flow characteristics and residence time. Lacustrine wetlands refers to open bays, protected bays, and barrier-protected wetlands. Barrier-protected wetlands are separated from the Great Lakes by porous sand or gravel barriers, allowing water level and chemical influence from the lake, but protection from storm erosion. Connecting channels refers to the major rivers linking the Great Lakes, including the St. Mary’s, Detroit, and St. Clair Rivers, all characterized by a large flow, but seasonally stable hydrology. Riverine aquatic system refers to smaller rivers tributary to the Great Lakes whose water quality, flow rate, and sediment load are controlled in large part by their individual drainages, but with Great Lakes influence near their mouth, where large wetlands are located.

Soils

Where bedrock is at or near the surface, bedrock chemistry affects wetland species composition. Soils derived from Precambrian crystalline bedrock along Lake Superior are generally acid and favor the development of poor fen or bog communities. In contrast, soils derived from marine deposits in the lower Great Lakes, including shale and marine limestone, dolomite, and evaporites, are typically more calcareous (less acid), creating the preferred habitat for calciphilic aquatic plant species and development of more minerotrophic communities such as wet meadow and coastal fen.

Natural Processes

Water level fluctuations greatly influence vegetation patterning. Fluctuations occur over three temporal scales: short-term fluctuations (seiche) in water level caused by persistent winds and/or differences in barometric pressure; seasonal fluctuations reflecting the annual hydrologic cycle in the Great Lakes basin; and interannual fluctuations in lake level as a result of variable precipitation and evaporation within their drainage basins. Interannual fluctuations of 3.5 to 6.5 feet (1.3 to 2.5 m) result in changes in water current, wave action, turbidity, nutrient content or availability, alkalinity, and temperature. Coastal wetland systems are adapted to and require periodic inundation. Seiches, storms, and water level cycles strikingly change vegetation over short periods by destroying some vegetation zones, creating others, and forcing all zones to shift lakeward or landward to accommodate water levels. Coastal wetlands are also affected by longshore currents and storm waves. Wind and wave action and ice scour are the primary agents responsible for shoreline erosion and redeposition of sediments in marshes.

Vegetation

There are three distinct zones within most Great Lakes marshes: wet meadow, emergent marsh, and submergent marsh. The wet meadow zone typically has shallow, saturated organic soils, but in some years it can be flooded throughout the growing season. Grasses and sedges typically dominate the wet meadow zone, along with numerous other herbaceous genera. During dry periods, shrubs and tree seedlings commonly establish. The emergent marsh zone is permanently flooded with shallow water throughout the growing season in most years, but can be dry when Great Lakes water levels are low. Dominant plants in the emergent marsh zone include bulrushes (Scirpus spp. and Schoenoplectus spp.), spike-rushes (Eleocharis spp.), rushes (Juncus spp.), and cat-tails (Typha spp.), in addition to submergent and floating plants. The submergent zone has deep water and few or no emergent species. Dominant plants in the submergent marsh zone include numerous floating or submergent species.

Based on vegetation sampling of 102 Great Lakes marshes, only one plant was considered common (i.e., present in 80% or more of the marshes): bluejoint grass (Calamagrostis canadensis), which occurs in the wet meadow zone. Additional plants of the wet meadow zone include marsh bell flower (Campanula aparinoides), sedges (Carex aquatilis, C. lacustris, and C. stricta), water hemlock (Cicuta bulbifera), jewelweed (Impatiens capensis), small bedstraw (Galium trifidum), water smartweed (Persicaria amphibia), marsh cinquefoil (Comarum palustre), common skullcap (Scutellaria galericulata), broad-leaved cat-tail (Typha latifolia), and the invasive species, narrow-leaved cat-tail (T. angustifolia). Plants of the emergent zone include hard stem bulrush (Schoenoplectus acutus), three-square (S. pungens), spike-rush (Eleocharis palustris), common arrowhead (Sagittaria latifolia), and several other submergent and floating species. Plants of the submergent marsh and open flooded portions of the emergent zone include pondweed (Potamogeton natans), water-celery (Vallisneria americana), common waterweed (Elodea canadensis), bladderwort (Utricularia vulgaris), coontail (Ceratophyllum demersum), slender naiad (Najas flexilis), and sweet-scented water-lily (Nymphaea odorata).

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Submergent Plants

- coontail (Ceratophyllum demersum)

- common waterweed (Elodea canadensis)

- slender naiad (Najas flexilis)

- pondweeds (Potamogeton obtusifolius, P. pectinatus, P. richardsonii, P. robbinsii, P. zosteriformis, Stuckenia pectinata, and others)

- bladderworts (Utricularia intermedia, U. vulgaris, and others)

- water-celery (Vallisneria americana)

Rooted Floating-leaved Plants

- water-shield (Brasenia schreberi)

- variegated yellow pond-lilies (Nuphar advena and N. variegata)

- sweet-scented waterlily (Nymphaea odorata)

- pondweeds (Potamogeton gramineus, P. illinoensis, P. natans, and others)

Non-rooted Floating Plants

- small duckweed (Lemna minor)

- star duckweed (Lemna trisulca)

- red duckweed (Lemna turionifera)

- great duckweed (Spirodela polyrhiza)

- water meal (Wolffia spp.)

Emergent Plants

Graminoids

- ticklegrasses (Agrostis hyemalis and A. scabra)

- blue-joint (Calamagrostis canadensis)

- narrow-leaved reedgrass (Calamagrostis stricta)

- sedges (Carex aquatilis, C. bebbii, C. comosa, C. hystericina, C. lacustris, C. lasiocarpa, C. stricta, C. viridula, and others)

- twig-rush (Cladium mariscoides)

- tufted hair grass (Deschampsia cespitosa)

- Lindheimer’s panic grass (Dichanthelium lindheimeri)

- spike-rushes (Eleocharis acicularis, E. elliptica, E. palustris, E. quinqueflora, and others)

- rushes (Juncus balticus, J. brevicaudatus, J. canadensis, and others)

- cut grass (Leersia oryzoides)

- common reed (Phragmites australis subsp. americanus)

- beak-rush (Rhynchospora capillacea)

- hardstem bulrush (Schoenoplectus acutus)

- threesquare (Schoenoplectus pungens)

- softstem bulrush (Schoenoplectus tabernaemontani)

- bulrushes (Scirpus atrovirens and S. cyperinus)

Forbs

- Canada anemone (Anemone canadensis)

- swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata)

- hedge bindweed (Calystegia sepium)

- marsh bellflower (Campanula aparinoides)

- water hemlock (Cicuta bulbifera)

- limestone calamint (Clinopodium arkansanum)

- marsh cinquefoil (Comarum palustre)

- common boneset (Eupatorium perfoliatum)

- grass-leaved goldenrod (Euthamia graminifolia)

- joe-pye-weed (Eutrochium maculatum)

- small bedstraw (Galium trifidum)

- small fringed gentian (Gentianopsis virgata)

- swamp mallow (Hibiscus moscheutos)

- jewelweed (Impatiens capensis)

- wild blue flag (Iris versicolor)

- marsh pea (Lathyrus palustris)

- Kalm’s lobelia (Lobelia kalmii)

- common water horehound (Lycopus americanus)

- balsam ragwort (Packera paupercula)

- grass-of-Parnassus (Parnassia glauca)

- water smartweed (Persicaria amphibia)

- pickerel-weed (Pontederia cordata)

- silverweed (Potentilla anserina)

- bird’s-eye primrose (Primula mistassinica)

- common arrowhead (Sagittaria latifolia)

- common skullcap (Scutellaria galericulata)

- Ohio goldenrod (Solidago ohioensis)

- bur-reeds (Sparganium spp.)

- nodding ladies’-tresses (Spiranthes cernua)

- panicled aster (Symphyotrichum lanceolatum)

- bog arrow-grasses (Triglochin maritima and T. palustris)

- broad-leaved cat-tail (Typha latifolia)

- horned bladderwort (Utricularia cornuta)

- blue vervain (Verbena hastata)

Ferns

- marsh fern (Thelypteris palustris)

Fern Allies

- common horsetail (Equisetum arvense)

- water horsetail (Equisetum fluviatile)

Shrubs

- tag alder (Alnus incana)

- silky dogwood (Cornus amomum)

- red-osier dogwood (Cornus sericea)

- shrubby cinquefoil (Dasiphora fruticosa)

- Kalm’s St. John’s-wort (Hypericum kalmianum)

- sweet gale (Myrica gale)

- willows (Salix candida, S. exigua, S. petiolaris, and others)

- meadowsweet (Spiraea alba)

Trees

- paper birch (Betula papyrifera)

- green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica)

- balsam poplar (Populus balsamifera)

- quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides)

Noteworthy Animals

Great Lakes coastal wetlands provide important habitat for insects, fish, waterfowl, water birds, and mammals. Over 50 species of fish, including several game fish, have been documented to utilize the coastal wetlands of northern Lake Huron. Fish utilize coastal wetlands in all parts of their life cycle, including egg, larval, immature, and adult stages. A broad range of invertebrates occupy this habitat, providing food for fish, birds, herptiles, and small mammals. Coastal wetlands have long been recognized as critical habitat for the migration, feeding, and nesting of waterfowl and shorebirds. The Great Lakes and connecting rivers are parts of several major flyways. During spring migration, when few alternative sources of nutrients are available, terrestrial migratory songbirds feed on midges from the Great Lakes marshes. Mammals utilizing coastal wetlands include beaver, muskrat, river otter, and mink.

Rare Plants

- Hibiscus laevis (smooth rose-mallow, state special concern)

- Hibiscus moscheutos (rose mallow, state special concern)

- Nelumbo lutea (American lotus, state threatened)

- Sagittaria montevidensis (arrowhead, state threatened)

- Zizania aquatica var. aquatica (wild rice, state threatened)

Rare Animals

- Botaurus lentiginosus (American bittern, state special concern)

- Chlidonias niger (black tern, state special concern)

- Circus cyaneus (northern harrier, state special concern)

- Cistothorus palustris (marsh wren, state special concern)

- Elaphe vulpina gloydi (eastern fox snake, state threatened)

- Emydoidea blandingii (Blanding’s turtle, state special concern)

- Falco columbarius, (merlin, state threatened)

- Ixobrychus exilis (least bittern, state threatened)

- Nycticorax nycticorax (black crowned night-heron, state special concern)

- Rallis elegans (king rail, state endangered)

- Somatochlora hineana (Hine’s emerald, federal/state endangered)

- Sterna forsteri (Forster’s tern, state special concern)

- Xanthocephalus xanthocephalus (yellow-headed blackbird, state special concern)

Biodiversity Management Considerations

Water-level control has altered natural wetland dynamics. All the connecting channels have been modified to accommodate shipping, resulting in increased shoreline erosion. Agricultural drainage has eliminated large areas of marshes, and agricultural sedimentation has greatly increased turbidity, eliminating submergent species that require clear water. The resulting deposition of rich organic sediments in the wet meadow zone and along the shoreline favors early-successional species. Nutrient loading has locally reduced oxygen levels, prompted algal blooms, and led to the dominance of high-nutrient tolerant species such as cat-tails.

Urban development degrades and eliminates coastal marshes through pollution, land management, and ecosystem alteration. Armoring shoreline and dredging of harbors eliminate marshes. Dumping of waste materials such as sawdust, sewage, and chemicals alters shallow-water marsh environments, increasing turbidity, reducing oxygen levels, and altering the pH. Shipping traffic erodes shoreline vegetation through excessive wave action. Introductions of invasive plants and animals have altered community structure and species composition. Many invasive species arrive in shipping ballast, while others are purposefully introduced. Some of the invasive plants that threaten the diversity and community structure of Great Lakes marsh include reed (Phragmites australis subsp. australis), narrow-leaved cat-tail (Typha angustifolia), hybrid cat-tail (Typha xglauca), reed canary grass (Phalaris arundinacea), purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), frogbit (Hydrocharis morsus-ranae), hydrilla (Hydrilla verticillata), watercress (Nasturtium microphyllum), and European marsh thistle (Cirsium palustre).

Maintaining hydrologic regimes, in addition to eliminating off-road vehicle (ORV) traffic, nutrient and sediment inputs, and invasive species populations, is integral to protecting the ecological integrity of high quality Great Lakes marshes.

Variation

There are several regionally distinctive marsh types due to regional differences in geomorphology, water chemistry, and land use. These types include Lake Superior’s poor fens, rich fens in the Straits of Mackinac, lacustrine estuaries or buried river mouth on Lake Michigan, Saginaw Bay lakeplain marshes, and Lake Erie-Lake St. Clair lakeplain marshes.

Similar Natural Communities

Submergent marsh, emergent marsh, northern wet meadow, southern wet meadow, interdunal wetland, poor fen, coastal fen, northern fen, lakeplain wet prairie, lakeplain wet-mesic prairie, northern shrub thicket, southern shrub-carr, and wooded dune and swale complex.

Places to Visit

- Duncan Bay, Cheboygan State Park, Cheboygan Co.

- El Cajon Bay and Misery Bay, Atlanta State Forest Management Unit, Alpena Co.

- Munuscong River Mouth, Sault Sainte Marie State Forest Management Unit, Chippewa Co.

- Pinconning, Pinconning County Park, Bay Co.

- Pointe Aux Chenes, Hiawatha National Forest, Mackinac Co.

- Pottawattomie Bayou, Grand Haven Township Park, Ottawa Co.

- St. Martin Bay, Hiawatha National Forest, Mackinac Co.

- Waugoshance Point, Wilderness State Park, Emmet Co.

- Wildfowl Bay Islands, Wildfowl Bay Wildlife Area, Huron Co.

Relevant Literature

- Albert, D.A. 2001. Natural community abstract for Great Lakes marsh. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 11 pp.

- Albert, D.A. 2003. Between land and lake: Michigan’s Great Lakes coastal wetlands. Michigan Natural Features Inventory. Michigan State University Extension, East Lansing, MI. Bulletin E-2902. 96 pp.

- Albert, D.A., D.A. Wilcox, J.W. Ingram, and T.A. Thompson. 2005. Hydrogeomorphic classification for Great Lakes coastal wetlands. Journal of Great Lakes Research. 31 (Supplement 1): 129-146.

- Harris, H.J., T.R. Bosley, and F.D. Rosnik. 1977. Green Bay’s coastal wetlands: A picture of dynamic change. Pp. 337-358 in Wetlands, ecology, values, and impacts: Proceedings of the Waubesa Conference on Wetlands, ed. C.B. DeWitt and E. Soloway. Institute of Environmental Studies, University of Wisconsin, Madison.

- Herdendorf, C.E., S.M. Hartley, and M.D. Barnes, eds. 1981. Fish and wildlife resources of the Great Lakes coastal wetlands within the United States. Volume 1, Overview. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, FWS/OBS-81/02-v1.

- Keddy, P.A., and A.A. Reznicek. 1986. Great Lakes vegetation dynamics: The role of fluctuating water levels and buried seeds. Journal of Great Lakes Research 12: 25-36.

- Keough, J.R., T.A. Thompson, G.R. Guntenspergen, and D.A. Wilcox. 1999. Hydrogeomorphic factors and ecosystem responses in coastal wetlands of the Great Lakes. Wetlands 19: 821-834.

- Minc, L.D. 1997. Great Lakes coastal wetlands: An overview of abiotic factors affecting their distribution, form, and species composition. A report in three parts. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 307 pp.

For a full list of references used to create this description, please refer to the natural community abstract for Great Lakes Marsh.

More Information

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: March 5, 2026).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.