Sandstone Bedrock Lakeshore

Overview

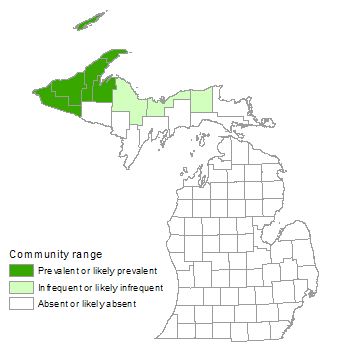

Sandstone bedrock lakeshore is a sparsely vegetated community that occurs along the Lake Superior shoreline in the central and western Upper Peninsula. Exposed sandstone bedrock is prominent, with lichens and mosses locally dominant, and scattered sedges, grasses, forbs, shrubs, and occasionally trees restricted to cracks, joints, and depressions in the bedrock.

Rank

Global Rank: G4G5 - Rank is uncertain, ranging from apparently secure to secure

State Rank: S2 - Imperiled

Landscape Context

Sandstone bedrock lakeshore occurs along the shores of Lake Superior as part of the Copper Harbor Conglomerate, Jacobsville Sandstone, and Nonesuch and Freda Formations, stretching from the Wisconsin-Michigan boundary in the west to east of Munising in Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore. The largest continuous stretch of sandstone bedrock lakeshore in Michigan occurs along Lake Superior within Porcupine Mountain Wilderness State Park, where much of the bedrock tilts northward toward the lake. Level areas of sandstone bedrock lakeshore occur along Keweenaw Bay on Point Abbaye in Baraga County.

Sandstone bedrock lakeshore is typically bordered along its inland margin by boreal forest, mesic northern forest, and occasionally by forested wetlands. Along the shoreline, sandstone bedrock lakeshore is interspersed with areas of sandstone lakeshore cliff, granite bedrock lakeshore, granite lakeshore cliff, volcanic bedrock lakeshore, volcanic cobble shore, and sand and gravel beach.

Soils

Almost no soil development occurs on the sandstone bedrock. Soil development and plant establishment are limited to cracks, joints, and depressions in the bedrock where small amounts of sand and organic matter accumulate. The breakdown of sandstone and plant matter results in an acidic, sandy, organic-rich soil. Soil depth is shallow due to wave, wind, and ice action.

Natural Processes

Storms, wind, winter ice scour, fluctuating water levels, and severe desiccation produce a stressful, unstable environment for vegetation establishment and growth. Changes in Great Lakes water levels result in vegetation colonizing recently exposed cracks, joints, and depressions in the bedrock during periods of low water. When water levels rise, the sparse vegetation is submerged or pounded, and scoured by waves and ice. Thin soils, full exposure, and high winds combine to produce severely desiccating conditions, especially during summer droughts. Frequent fog serves to mitigate drought stress. Windthrow is common along the inland margin, where trees are able to mature but are typically shallowly rooted.

Vegetation

Sandstone bedrock lakeshore is a sparsely vegetated community supporting a flora of lichens, mosses, herbaceous plants, shrubs, and dwarfed trees. Mature tree cover is generally limited to the inland edge. Most vegetation grows from cracks and joints in the bedrock. Small pools of water, which support wetland plants along their edges, collect in isolated depressions from storm waves or where small intermittent streams flow across the bedrock. Common herbaceous plants include hair grass (Deschampsia cespitosa), upland white goldenrod (Solidago ptarmicoides), Gillman’s goldenrod (S. simplex), grass-leaved goldenrod (Euthamia graminifolia), harebell (Campanula rotundifolia), bog lobelia (Lobelia kalmii), balsam ragwort (Packera paupercula), wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana), jewelweed (Impatiens capensis), northern bugleweed (Lycopus uniflorus), sedge (Carex viridula), fireweed (Chamerion angustifolium), and rushes (Juncus spp.). Common shrubs, mostly occurring in a dwarfed condition, include ninebark (Physocarpus opulifolius), wild rose (Rosa acicularis), serviceberries (Amelanchier spp.), thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus), mountain alder (Alnus viridis), pussy willow (Salix discolor), and Bebb’s willow (S. bebbiana). Common trees, mostly occurring as small seedlings and saplings, include northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis), balsam poplar (Populus balsamifera), quaking aspen (P. tremuloides), red maple (Acer rubrum), paper birch (Betula papyrifera), and white ash (Fraxinus americana). Additional shrubs and trees growing along the inland margins include choke cherry (Prunus virginiana), bush honeysuckle (Diervilla lonicera), American fly honeysuckle (Lonicera canadensis), hemlock (Tsuga canadensis), white spruce (Picea glauca), balsam fir (Abies balsamea), yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis), sugar maple (A. saccharum), and quaking aspen.

Invasive species observed in sandstone bedrock lakeshore include redtop (Agrostis gigantea), spotted knapweed (Centaurea stoebe), ox-eye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare), glaucous king devil (Hieracium piloselloides), common St. John’s-wort (Hypericum perforatum), Canada bluegrass (Poa compressa), Kentucky bluegrass (P. pratensis), reed canary grass (Phalaris arundinacea), sheep sorrel (Rumex acetosella), garden tansy (Tanacetum vulgare), and common mullein (Verbascum thapsus).

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Graminoids

- little green sedge (Carex viridula)

- tufted hair grass (Deschampsia cespitosa)

- Baltic rush (Juncus balticus)

- knotted rush (Juncus nodosus)

Forbs

- harebell (Campanula rotundifolia)

- fireweed (Chamerion angustifolium)

- common boneset (Eupatorium perfoliatum)

- grass-leaved goldenrod (Euthamia graminifolia)

- joe-pye-weed (Eutrochium maculatum)

- wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana)

- jewelweed (Impatiens capensis)

- Kalm’s lobelia (Lobelia kalmii)

- northern bugle weed (Lycopus uniflorus)

- balsam ragwort (Packera paupercula)

- mad-dog skullcap (Scutellaria lateriflora)

- upland white goldenrod (Solidago ptarmicoides)

- Gillman’s goldenrod (Solidago simplex)

- purple meadow-rue (Thalictrum dasycarpum)

Shrubs

- mountain alder (Alnus viridis)

- serviceberries (Amelanchier spp.)

- bush honeysuckle (Diervilla lonicera)

- Canadian fly honeysuckle (Lonicera canadensis)

- sweet gale (Myrica gale)

- ninebark (Physocarpus opulifolius)

- choke cherry (Prunus virginiana)

- wild rose (Rosa acicularis)

- thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus)

- Bebb’s willow (Salix bebbiana)

- pussy willow (Salix discolor)

- soapberry (Shepherdia canadensis)

Trees

- balsam fir (Abies balsamea)

- red maple (Acer rubrum)

- juneberry (Amelanchier arborea)

- yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis)

- paper birch (Betula papyrifera)

- white ash (Fraxinus americana)

- green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica)

- white spruce (Picea glauca)

- white pine (Pinus strobus)

- balsam poplar (Populus balsamifera)

- quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides)

- northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis)

Noteworthy Animals

The high-energy environment of sandstone bedrock lakeshore appears to provide little stable habitat for terrestrial insects, but the sediments, rock surfaces, and pools are likely important habitat for aquatic invertebrates.

Rare Plants

- Carex atratiformis (sedge, state threatened)

- Trisetum spicatum (downy oatgrass, state special concern)

Rare Animals

- Falco columbarius (merlin, state threatened)

- Falco peregrinus (peregrine falcon, state endangered)

- Haliaeetus leucocephalus (bald eagle, state threatened)

Biodiversity Management Considerations

Excessive trampling or off-road vehicle use can kill lakeshore vegetation. The loss of vegetation can accelerate soil loss through wind, rain, or wave action. After soil has been lost, soil development and plant reestablishment are slow. Eliminating illegal off-road vehicle activity is a primary means of protecting the ecological integrity of sandstone bedrock lakeshore and associated shoreline communities. Invasive species that threaten the diversity and community structure of sandstone bedrock lakeshore include redtop, spotted knapweed, ox-eye daisy, hawkweeds (Hieracium spp.), common St. John’s-wort, Canada bluegrass, Kentucky bluegrass, reed canary grass, sheep sorrel, garden tansy, and common mullein. Maintaining a mature, unfragmented forested buffer around sandstone bedrock lakeshores may help limit the local seed source for invasive species distributed by wind or birds. Monitoring and control efforts to detect and remove these and other invasive species will help maintain the native biodiversity of sandstone bedrock lakeshore and surrounding natural communities.

Variation

The sandstone bedrock along Lake Superior varies significantly in texture and erosion resistance, which can influence soil development and plant species composition.

Similar Natural Communities

Sandstone lakeshore cliff, volcanic bedrock lakeshore, granite bedrock lakeshore, limestone bedrock lakeshore, volcanic bedrock glade, granite bedrock glade, and volcanic lakeshore cliff.

Places to Visit

- Point Abbaye, Baraga State Forest Management Unit, Baraga Co.

- Pictured Rocks, Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore, Alger Co.

- Porcupine Shore, Porcupine Mountains Wilderness State Park, Ontonagon Co.

- Sleeping Misery Bay, Baraga State Forest Management Unit, Ontonagon Co.

Relevant Literature

- Albert, D.A., P. Comer, D. Cuthrell, D. Hyde, W. MacKinnon, M. Penskar, and M. Rabe. 1997. The Great Lakes bedrock lakeshores of Michigan. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 218 pp.

- Bornhorst, T.J., and W.I. Rose. 1994. Self-guided geological field trip to the Keweenaw Peninsula, Michigan. Proceedings of the Institute on Lake Superior Geology. Volume 40, Part 2. 185 pp.

- Dorr, J.A., Jr., and D.F. Eschman. 1970. Geology of Michigan. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI. 470 pp.

- Faber-Langendoen, D., ed. 2001. Plant communities of the Midwest: Classification in an ecological context. Association for Biodiversity Information, Arlington, VA. 61 pp. + appendix (705 pp.).

- LaBerge, G.L. 1994. Geology of the Lake Superior region. Geoscience Press. Phoenix, AZ. 313 pp.

- Reed, R.C., and J. Daniels. 1987. Bedrock geology of northern Michigan. State of Michigan Department of Natural Resources. Map: 1: 500,000.

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: May 18, 2025).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.