Limestone Bedrock Glade

Overview

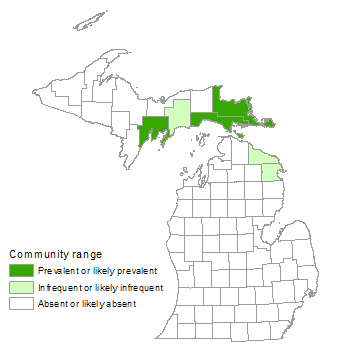

Limestone bedrock glade consists of an herb- and graminoid-dominated plant community with scattered clumps of stunted trees and shrubs growing on thin soil over limestone or dolomite. Tree cover is typically 10 to 25%, but occasionally as high as 60%. Shrub and herb cover is variable and there are typically areas of exposed bedrock. Mosses, lichens, and algae can be abundant on the exposed limestone bedrock or thin organic soils. Seasonal flooding and summer drought maintain the open conditions. In Michigan, limestone bedrock glade occurs in the Upper Peninsula near the shorelines of Lakes Huron and Michigan, concentrated in a band from Drummond Island to Cedarville and from Gould City to the Garden Peninsula. In the Northern Lower Peninsula, limestone bedrock glade occurs along the Lake Huron shoreline near Rogers City, Alpena, and Thompson’s Harbor. This community is also referred to as alvar glade.

Rank

Global Rank: G2G4

State Rank: S2 - Imperiled

Landscape Context

Limestone bedrock glade is most abundant along the Niagaran Escarpment, which is exposed on or near the north shores of Lakes Michigan and Huron, extending as far west as Wisconsin and as far east as the eastern Lake Ontario shoreline of New York. Limestone bedrock is also exposed in Presque Isle and Alpena Counties of Lower Michigan. Much of the limestone along the Niagaran Escarpment has been converted through geological processes to dolomite, a magnesium-rich form of limestone. Most of the limestone bedrock is relatively flat, with a very gradual slope to the south, but there are a few areas of limestone cliff as well. Limestone bedrock glade often occurs adjacent to limestone cobble shore, limestone bedrock lakeshore, alvar (alvar grassland), and boreal forest.

Soils

While large areas of limestone are bare of soil, where soils have developed, they are typically organic soils less than 30 cm (12 in) in depth. Soils are circumneutral and are generally saturated or flooded in the fall and spring, but are often droughty during summer months. Where there is no surface soil development, organic soils may accumulate in broad cracks (grykes) in the limestone pavement, where shrubs and trees often establish.

Natural Processes

The combination of flooded conditions in the spring and fall, with droughty conditions during the summer, maintains open conditions where trees are scattered and stunted. Seasonal flooding is less prevalent where there are abundant cracks in the rock, which provide improved internal drainage. However, sites with internal drainage are more prone to early desiccation and drought. Lightning fires may occasionally burn these sites, and there is speculation that Native Americans were responsible for some fires into the mid- to late nineteenth century. Strong winds off the Great Lakes result in windthrow of mature trees, which are shallowly rooted in the thin soils. Browsing by ungulates influences woody species composition and structure.

Vegetation

Limestone bedrock glade consists of an herb- and graminoid-dominated plant community with scattered clumps of stunted trees and shrubs. Tree cover typically ranges between 10 and 25%, with maximum tree cover of 60%. Dominant trees of the scattered and stunted canopy include northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis), white spruce (Picea glauca), paper birch (Betula papyrifera), and balsam fir (Abies balsamea). Additional characteristic trees include quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides) and balsam poplar (P. balsamifera). Common shrubs include soapberry (Shepherdia canadensis), bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi), choke cherry (Prunus virginiana), snowberry (Symphoricarpus albus), red-osier dogwood (Cornus sericea), common juniper (Juniperus communis), alder-leaved buckthorn (Rhamnus alnifolia), and bush honeysuckle (Diervilla lonicera). Common herbs include Canada mayflower (Maianthemum canadense), wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana), large-leaved aster (Eurybia macrophylla), small yellow lady’s-slipper (Cypripedium parviflorum var. makasin), yarrow (Achillea millefolium), wild columbine (Aquilegia canadensis), dwarf lake iris (Iris lacustris, federal/state threatened), wood lily (Lilium philadelphicum), balsam ragwort (Packera paupercula), northern bog violet (Viola nephrophylla), smooth aster (Symphyotrichum laeve), harebell (Campanula rotundifolia), Indian paintbrush (Castilleja coccinea), and cow-wheat (Melampyrum lineare). Characteristic grasses and sedges include poverty grass (Danthonia spicata), slender wheat grass (Elymus trachycaulus), rough-leaved rice grass (Oryzopsis asperifolia), ebony sedge (Carex eburnea), and Richardson’s sedge (Carex richardsonii, state special concern). Bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum) can also be common.

Vegetation zonation is minimal in limestone bedrock glade but some patterns may be evident. Large crevices provide additional moisture, nutrients, and footholds that allow shrubs and trees as well as herbaceous species to establish. Open portions of the glade, characterized by shallow soils, tend to support greater concentrations of herbs, lichens, and mosses. Nostoc and other algae are often concentrated in small, seasonally wet depressions.

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Graminoids

- Kalm’s brome (Bromus kalmii)

- beauty sedge (Carex concinna)

- ebony sedge (Carex eburnea)

- sedge (Carex garberi)

- Richardson’s sedge (Carex richardsonii)

- poverty grass (Danthonia spicata)

- tufted hair grass (Deschampsia cespitosa)

- Lindheimer’s panic grass (Dichanthelium lindheimeri)

- slender wheat grass (Elymus trachycaulus)

- rough-leaved rice grass (Oryzopsis asperifolia)

- little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium)

Forbs

- yarrow (Achillea millefolium)

- small pussytoes (Antennaria howellii)

- white camas (Anticlea elegans)

- wild columbine (Aquilegia canadensis)

- Cooper’s milk-vetch (Astragalus neglectus)

- harebell (Campanula rotundifolia)

- Indian paintbrush (Castilleja coccinea)

- Hill’s thistle (Cirsium hillii)

- limestone calamint (Clinopodium arkansanum)

- bastard-toadflax (Comandra umbellata)

- lance-leaved coreopsis (Coreopsis lanceolata)

- small yellow lady-slipper (Cypripedium parviflorum var. makasin)

- large yellow lady-slipper (Cypripedium parviflorum var. pubescens)

- large-leaved aster (Eurybia macrophylla)

- wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana)

- barren-strawberry (Geum fragarioides)

- dwarf lake iris (Iris lacustris )

- wood lily (Lilium philadelphicum)

- twinflower (Linnaea borealis)

- starry false Solomon-seal (Maianthemum stellatum)

- cow-wheat (Melampyrum lineare)

- rock sandwort (Minuartia michauxii)

- balsam ragwort (Packera paupercula)

- sweet-coltsfoot (Petasites frigidus)

- Alaska orchid (Platanthera unalascensis)

- gay-wings (Polygala paucifolia)

- bird’s-eye primrose (Primula mistassinica)

- early buttercup (Ranunculus fascicularis)

- black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta)

- old-field goldenrod (Solidago nemoralis)

- upland white goldenrod (Solidago ptarmicoides)

- smooth aster (Symphyotrichum laeve)

Ferns

- maidenhair spleenwort (Asplenium trichomanes)

- common polypody (Polypodium virginianum)

- bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum)

Lichens

- reindeer lichens (Cladina mitis and C. rangiferina)

- felt lichen (Peltigera canina)

Mosses

- schistidium mosses (Schistidium spp.)

- tortella moss (Tortella spp.)

Shrubs

- serviceberries (Amelanchier spp.)

- bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi)

- bunchberry (Cornus canadensis)

- red-osier dogwood (Cornus sericea)

- bush honeysuckle (Diervilla lonicera)

- Kalm’s St. John’s-wort (Hypericum kalmianum)

- common juniper (Juniperus communis)

- creeping juniper (Juniperus horizontalis)

- choke cherry (Prunus virginiana)

- alder-leaved buckthorn (Rhamnus alnifolia)

- wild rose (Rosa blanda)

- dwarf raspberry (Rubus pubescens )

- soapberry (Shepherdia canadensis)

- snowberry (Symphoricarpos albus)

Trees

- balsam fir (Abies balsamea)

- paper birch (Betula papyrifera)

- white spruce (Picea glauca)

- white pine (Pinus strobus)

- balsam poplar (Populus balsamifera)

- quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides)

- northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis)

Noteworthy Animals

Several ant species occupy various habitats within the glade, nesting beneath rocks, in dead wood, and in live wood of the drought-stressed trees. The abundance of ants and other insects attracts black bears, which are common in some areas of limestone bedrock. The lime-rich habitat is home to many species of land snail as well, and the open grassland vegetation provides habitat for many prairie insects.

Rare Plants

- Astragalus neglectus (Cooper’s milk vetch, state special concern)

- Calypso bulbosa (calypso, state threatened)

- Carex concinna (beauty sedge, state special concern)

- Carex richardsonii (Richardson’s sedge, state special concern)

- Carex scirpoidea (bulrush sedge, state threatened)

- Cirsium hillii (Hill’s thistle, state special concern)

- Cypripedium arietinum (ram’s-head lady’s-slipper, state special concern)

- Iris lacustris (dwarf lake iris, federal/state threatened)

- Piperia unalascensis (Alaska orchid, state special concern)

- Scutellaria parvula (small skullcap, state threatened)

Rare Animals

- Flexamia delongi (leafhopper, state special concern)

- Prosapia ignipectus (red-legged spittlebug, state special concern)

- Pyrgus wyandot (grizzled skipper, state special concern)

- Vallonia albula (land snail, state special concern)

- Vertigo elatior (tapered vertigo, state special concern)

- Vertigo hubrichti (Hubricht’s vertigo, state special concern)

- Vertigo nylanderi (deep-throat vertigo, state special concern)

- Vertigo paradoxa (land snail, state special concern)

- Vertigo pygmaea (crested vertigo, state special concern)

Biodiversity Management Considerations

Principal threats to limestone glade are overgrazing, alteration of hydrology from road construction and off-road vehicle use, development, dumping of waste materials, and quarry development. All of these disturbances provide pathways for the introduction or spread of invasive plant species. Off-road vehicle use has degraded several glades on Drummond Island and the Garden Peninsula. High deer densities, especially on the Garden Peninsula, are influencing community structure and are likely negatively impacting species diversity and northern white-cedar’s regeneration capacity.

Invasive species that threaten to reduce the diversity and alter the community structure of limestone bedrock glade include glossy buckthorn (Frangula alnus), common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica), spotted knapweed (Centaurea stoebe), ox-eye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare), Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis), and Canada bluegrass (P. compressa). Monitoring and control efforts to detect and remove these and other invasive species before they become widespread will help maintain the native biodiversity of limestone bedrock glade and surrounding natural communities.

Given that the thin soils and slow-growing lichen and moss cover are sensitive to anthropogenic disturbance and recover slowly, conservation efforts should focus on preserving the ecological integrity of existing high-quality limestone bedrock glades. Prescribed burns may provide a useful management tool to maintain open conditions and increase herbaceous plant diversity, yet the response of this plant community to fire has not been well documented.

Variation

Local variability is common in this community, due to differences in slope, amount and depth of crevices, and even composition of the bedrock. While all of the bedrock where the glades occur is classified as limestone or dolomite, locally the rock contains large amounts of silt, sand, or clay, resulting in a lack of solution cracks. Still other areas on Huron Bay, Drummond Island, consist of thinly bedded shaly limestone. All of this variability affects species composition, leading to differences in both dominance and vegetation density among occurrences.

Similar Natural Communities

Alvar, limestone bedrock lakeshore, limestone cobble shore, limestone lakeshore cliff, limestone cliff, and boreal forest.

Places to Visit

- East Lake Glade, Hiawatha National Forest, Chippewa Co.

- Kregg Bay Glade (Garden Peninsula), Shingleton State Forest Management Unit, Delta Co.

- Maxton Plains (Drummond Island), Sault Sainte Marie State Forest Management Unit and The Nature Conservancy (Maxton Plains Preserve), Chippewa Co.

- The Rock (Drummond Island), Sault Saint Marie State Forest Management Unit, Chippewa Co.

- Thompson's Harbor, Thompson's Harbor State Park, Presque Isle Co.

Relevant Literature

- Albert, D.A. 2007. Natural community abstract for limestone bedrock glade. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 7 pp.

- Albert, D.A., P. Comer, D. Cuthrell, D. Hyde, W. MacKinnon, M. Penskar, and M. Rabe. 1997. The Great Lakes bedrock lakeshores of Michigan. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 218 pp.

- Baskin, J.M., and C.C. Baskin. 1999. Cedar glades of the southeastern United States. Pp. 206-219 in Savannas, barrens, and rock outcrop plant communities of North America, ed. R.C. Anderson, J.S. Fralish, and J.M. Baskin. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 480 pp.

- Belcher, J.W., P.A. Keddy, and P.A. Catling. 1992. Alvar vegetation in Canada: A multivariate description at two scales. Canadian Journal of Botany 70: 1279-1291.

- Brownell, V.R., and J.L. Riley. 2000. The alvars of Ontario: Significant alvar natural areas in the Ontario Great Lakes region. Federation of Ontario Naturalists, Don Mills, ON. 269 pp.

- Catling, P.M. 1995. The extent of confinement of vascular plants to alvars in southern Ontario. Canadian Field Naturalist 109: 172-181.

- Catling, P.M., and V.R. Brownell. 1995. A review of alvars of the Great Lakes region: Distribution, floristic composition, biogeography, and protection. Canadian Field Naturalist 109: 143-171.

- Catling, P.M., and V.R. Brownell. 1998. Importance of fire in the maintenance of distinctive, high diversity plant communities on alvars — Evidence from the Burnt Lands, eastern Ontario. Canadian Field Naturalist 112: 662-667.

- Catling, P.M., and V.R. Brownell. 1999. Alvars of the Great Lakes region. Pp. 375-391 in Savannas, barrens, and rock outcrop plant communities of North America, ed. R.C.Anderson, J.S. Fralish, and J.M. Baskin. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 480 pp.

- Dorr, J.A., Jr., and D.F. Eschman. 1970. Geology of Michigan. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI. 470 pp.

- Faber-Langendoen, D., ed. 2001. Plant communities of the Midwest: Classification in an ecological context. Association for Biodiversity Information, Arlington, VA. 61 pp. + appendix (705 pp.).

- Jones, J., and C. Reschke. 2005. The role of fire in Great Lakes alvar landscapes. Michigan Botanist 44(1): 13-27.

- Lee, H.T., W.D. Bakowsky, J. Riley, J. Bowles, M. Puddister, P. Uhlig, and S. McMurray. 1998. Ecological land classification for southern Ontario: First approximation and its application. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Southcentral Science Section, Science Development and Transfer Branch. SCSS Field Guide FG-02.

- Lee, Y.M., L.J. Scrimger, D.A. Albert, M.R. Penskar, P.J. Comer, and D.L. Cuthrell. 1998. Alvars of Michigan. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 30 pp.

- Reed, R.C., and J. Daniels. 1987. Bedrock geology of northern Michigan. State of Michigan Department of Natural Resources. Map: 1: 500,000.

- Reschke, C., R. Reid, J. Jones, T. Feeney, and H. Potter. 1999. Conserving Great Lakes alvar: Final technical report of the international alvar conservation initiative. The Nature Conservancy, Chicago, IL. 241 pp.

- Schaefer, C.A., and D.W. Larson. 1997. Vegetation, environmental characteristics, and ideas on the maintenance of alvars on the Bruce Peninsula, Canada. Journal of Vegetation Science 8: 797-810.

- Stephenson, S.N., and P.S. Herendeen. 1986. Short-term drought effects on the alvar communities of Drummond Island, Michigan. Michigan Botanist 25: 16-27.

For a full list of references used to create this description, please refer to the natural community abstract for Limestone Bedrock Glade .

More Information

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: May 1, 2025).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.