Volcanic Cobble Shore

Overview

Volcanic cobble shore occurs along Lake Superior, predominantly in coves and gently curving bays between rocky points. These mostly unvegetated shores are often terraced, with the highest cobble beach ridge typically supporting a shrub zone several meters above Lake Superior.

Rank

Global Rank: G4G5 - Rank is uncertain, ranging from apparently secure to secure

State Rank: S3 - Vulnerable

Landscape Context

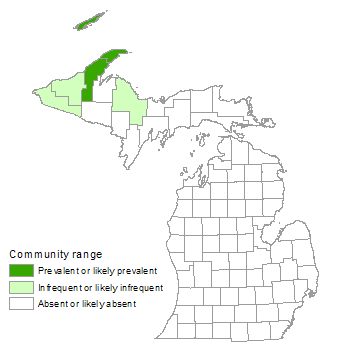

Volcanic cobble shore occurs in the northern Great Lakes region of the United States and Canada, ranging across the Lake Superior shoreline of Michigan, Minnesota, and Ontario. This cobble shore type is derived primarily from the erosion of the Copper Harbor Conglomerates, but includes weathered and eroded sandstone rock derived from other volcanic formations of Precambrian age, including the Portage Lake Volcanics. These shores, which are regularly disturbed by wave action and winter ice movements from the lake, are much steeper than most other cobble beaches encountered on the lower Great Lakes. Most of the shore has little or no vegetation, probably due to regular disturbance by storm waves, which move and reshape the cobble. The highest beach ridge, where scattered shrub vegetation typically establishes, is disturbed only infrequently by the most severe storm waves.

Volcanic cobble shore is typically bordered along its inland edge by boreal forest, dry-mesic northern forest, or mesic northern forest, and occasionally by volcanic bedrock glade. Where streams flow through the community, northern shrub thicket may occasionally border its upper edge. Along the shoreline, volcanic cobble shore is interspersed with areas of volcanic bedrock lakeshore, volcanic lakeshore cliff, and sand and gravel beach.

Soils

Little or no soil development occurs on volcanic cobble shore. The few plants that establish probably root in sand and gravel deposits under the cobble, which can be more than a meter in depth. On the Keweenaw Peninsula, the size of the cobbles ranges from 2 to 3 cm (0.75 to 1 in) in diameter to over 20 cm (8 in) in diameter, and large sections of the shoreline consist of similar-sized cobbles. The largest cobbles are located at the extreme east end of the peninsula, where the cobble shoreline is steepest and storm waves the most severe.

Natural Processes

Storm waves, erosion by ice-blocks, and desiccation are the primary forms of natural disturbance and act to limit vegetation establishment. Storm waves and ice movement can rearrange cobble shore, form and remove terraces, and uproot and bury plants. Plant establishment in deep cobble is limited by desiccating conditions from full exposure to sun and wind and a lack of moisture during summer droughts. Groundwater seepage, storm waves, and streams, both perennial and intermittent, provide a source of moisture for vegetation in some areas of the community during dry periods. Windthrow is common along the forested edge due to strong winds associated with Lake Superior storms.

Vegetation

Volcanic cobble shore is a sparsely vegetated community. On most sites, the lower beach is free of vegetation due to wave and ice action. Most vegetation is concentrated on the top of the coarse, cobble beach ridge, where scattered shrubs are typically dominant. The most commonly occurring species include ninebark (Physocarpus opulifolius), mountain alder (Alnus viridis), mountain ash (Sorbus decora), and marsh pea (Lathyrus palustris). Additional common herbaceous species include blue wild rye (Elymus glaucus, state special concern), evening primrose (Oenothera biennis), Canada dogwood (Cornus canadensis), bluejoint grass (Calamagrostis canadensis), grass-leaved goldenrod (Euthamia graminifolia), and horsetail (Equisetum hyemale). Additional common shrubs include wild red raspberry (Rubus strigosus), wild rose (Rosa acicularis), red-osier dogwood (Cornus sericea), bush honeysuckle (Diervilla lonicera), soapberry (Shepherdia canadensis), and northern gooseberry (Ribes oxyacanthoides, state special concern). Scattered trees are typically located along the inland edges of the community and include mountain ash, white spruce (Picea glauca), northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis), balsam fir (Abies balsamea), quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides), and paper birch (Betula papyrifera).

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Graminoids

- blue-joint (Calamagrostis canadensis)

- tufted hair grass (Deschampsia cespitosa)

- blue wild-rye (Elymus glaucus)

Forbs

- fireweed (Chamerion angustifolium)

- grass-leaved goldenrod (Euthamia graminifolia)

- marsh pea (Lathyrus palustris)

- evening primrose (Oenothera biennis)

Fern Allies

- scouring rush (Equisetum hyemale)

Shrubs

- mountain alder (Alnus viridis)

- red-osier dogwood (Cornus sericea)

- bush honeysuckle (Diervilla lonicera)

- ninebark (Physocarpus opulifolius)

- northern gooseberry (Ribes oxyacanthoides)

- wild rose (Rosa acicularis)

- wild red raspberry (Rubus strigosus)

- soapberry (Shepherdia canadensis)

Trees

- balsam fir (Abies balsamea)

- paper birch (Betula papyrifera)

- white spruce (Picea glauca)

- quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides)

- mountain-ash (Sorbus decora)

- northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis)

Noteworthy Animals

The high-energy environment of the cobble shore appears to provide little stable habitat for terrestrial insects, but the sediments and rock surfaces are sometimes rich in aquatic invertebrates.

Rare Plants

- Carex atratiformis (sedge, state threatened)

- Polygonum viviparum (alpine bistort, state threatened)

- Trisetum spicatum (downy oatgrass, state special concern)

Rare Animals

- None documented.

Biodiversity Management Considerations

Off-road vehicles (ORVs) are commonly used to travel across volcanic cobble shores, destroying vegetation and further reducing diversity. Eliminating illegal ORV activity is a primary means of protecting volcanic cobble shores. Maintaining a forested buffer will help prevent soil erosion and runoff into the community and may help reduce the local seed source of non-native invasive plants. Like other natural communities, monitoring and control efforts to detect and remove invasive plants will help protect the ecological integrity of volcanic cobble shore. Several invasive species that may have potential to colonize the community include reed (Phragmites australis subsp. australis), glossy buckthorn (Frangula alnus), and multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora).

Variation

Community structure and species composition are influenced by the size and type of pebbles or cobbles, steepness of shoreline slope, and presence or absence of terracing, groundwater seepage, and streams.

Similar Natural Communities

Limestone cobble shore, sandstone cobble shore, volcanic bedrock lakeshore, volcanic bedrock glade, and sand and gravel beach.

Places to Visit

- High Rock Bay, Baraga State Forest Management Unit, Keweenaw Co.

- Isle Royale National Park, Keweenaw Co.

- Keweenaw Point, Baraga State Forest Management Unit, Keweenaw Co.

- Porcupine Shore, Porcupine Mountains Wilderness State Park, Ontonagon Co.

Relevant Literature

- Albert, D.A., P. Comer, D. Cuthrell, D. Hyde, W. MacKinnon, M. Penskar, and M. Rabe. 1997. The Great Lakes bedrock lakeshores of Michigan. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 218 pp.

- Bornhorst, T.J., and W.I. Rose. 1994. Self-guided geological field trip to the Keweenaw Peninsula, Michigan. Proceedings of the Institute on Lake Superior Geology. Volume 40, Part 2. 185 pp.

- Dorr, J.A., Jr., and D.F. Eschman. 1970. Geology of Michigan. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI. 470 pp.

- Faber-Langendoen, D., ed. 2001. Plant communities of the Midwest: Classification in an ecological context. Association for Biodiversity Information, Arlington, VA. 61 pp. + appendix (705 pp.).

- Given, D.R., and J.H. Soper. 1981. The arctic-alpine element of the vascular flora at Lake Superior. National Museums of Canada, Publication in Botany 10: 1-70.

- LaBerge, G.L. 1994. Geology of the Lake Superior region. Geoscience Press, Phoenix, AZ. 313 pp.

- Reed, R.C., and J. Daniels. 1987. Bedrock geology of northern Michigan. State of Michigan Department of Natural Resources. Map: 1: 500,000.

- Slavick, A.D., and R.A. Janke. 1987. The vascular flora of Isle Royale National Park. Michigan Botanist 26: 91-134.

- Soper, J.H., and P.F. Maycock. 1962. A community of arctic-alpine plants of the east shore of Lake Superior. Canadian Journal of Botany 41: 183-198.

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: January 23, 2026).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.