Northern Bald

Overview

Northern bald is a low shrub and herbaceous community with scattered flagged trees and trees distorted into a krummholz growth form by branch breakage due to heavy snow, thick ice, and extreme winds off Lake Superior. Northern balds are restricted to large escarpments of volcanic bedrock ridges and are characterized by sparse vegetation, areas of exposed bedrock, and thin, slightly acidic soils. The community is also referred to as krummholz ridgetop.

Rank

Global Rank: GU - Unrankable

State Rank: S1 - Critically imperiled

Landscape Context

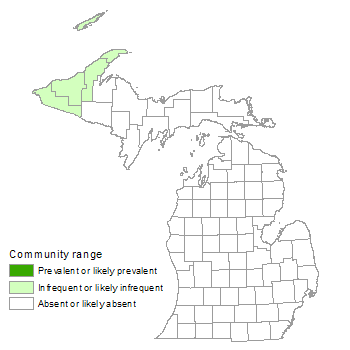

Northern balds are positioned along the top of high volcanic bedrock escarpments that rise above the adjacent hilly landscape. The escarpments consist of Precambrian-age Keweenawan Series bedrock, either basalts or basaltic conglomerates, occurring on Isle Royale and extending from near the northeastern tip of the Keweenaw Peninsula to the southwest into Houghton, Ontonagon, and Gogebic Counties. The surrounding forest types include dry-mesic northern forest and mesic northern forest.

Soils

The soils are thin, slightly acid sandy soil over bedrock. Areas of exposed bedrock that lack soil development are common. Thin organic sediments accumulate in joints, cracks, and depressions and are important substrates for vegetation.

Natural Processes

Extreme winds and ice storms characterize the northern bald community, causing trees in the scattered overstory to become flagged, a condition in which freezing winds kill branches on the windward side of the tree and the upper branches grow mainly from the leeward side of the tree, like a flag blowing from a flagpole. In addition, the harsh conditions result in some trees developing a krummholz form, a stunted, twisted condition common to subarctic or subalpine tree lines. The high winds and lack of soil development result in severe plant desiccation, despite the year-round occurrence of fog off Lake Superior. Although the thin soils promote extremely droughty conditions, the absence of full-grown trees is induced chiefly by the exposed ridge-top position, which promotes winter desiccation, ice and snow abrasion, and breakage by high winds. The lack of soil development and droughty conditions are further maintained on these bedrock ridge tops by rapid runoff following snow melt and rain events. Lastly, portions of the bedrock escarpment regularly slough off, forming talus slopes along the base of cliffs and exposing fresh, bare rock substrates.

Vegetation

Vegetation is scattered with areas of exposed bedrock common. Dominant tree species in the scattered, flagged overstory include white pine (Pinus strobus), red oak (Quercus rubra), and big-toothed aspen (Populus grandidentata). Balsam fir (Abies balsamea), white spruce (Picea glauca), and northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis) may also be common. Dominant shrubs include bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi), common juniper (Juniperus communis), staghorn sumac (Rhus typhina), and low sweet blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium). Additional shrubs include creeping juniper (Juniperus horizontalis) and choke cherry (Prunus virginiana). Fern diversity is high with the most common ferns being rusty woodsia (Woodsia ilvensis) and maidenhair spleenwort (Asplenium trichomanes). Other common ferns include Braun’s holly-fern (Polystichum braunii), northern holly-fern (P. lonchitis), and male fern (Dryopteris filix-mas, state special concern). Common ground flora include poverty grass (Danthonia spicata), wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana), western smartweed (Polygonum douglasii), prairie cinquefoil (Drymocallis arguta), three-toothed cinquefoil (Sibbaldiopsis tridentata), early saxifrage (Saxifraga virginiensis), ground cedar (Diphasiastrum tristachyum), and sand violet (Viola adunca). Sand club moss (Selaginella rupestris) is also common in some sites.

Northern balds may contain several vegetation zones. The ridge top is typically open, with only herbs and shrubs, while at slightly lower elevations, where winds may be less severe, dwarfed trees occur. Many of the ferns and rare plants, such as small blue-eyed Mary (Collinsia parviflora, state threatened), are concentrated along the south edge of escarpments, where there is typically a cliff. Talus slopes form along the base of the cliff. One rare plant, redstem ceanothus (Ceanothus sanguineus, state threatened), grows almost exclusively on the talus.

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Graminoids

- Pennsylvania sedge (Carex pensylvanica)

- poverty grass (Danthonia spicata)

- tufted hair grass (Deschampsia cespitosa)

- rice grass (Piptatherum pungens)

Forbs

- yarrow (Achillea millefolium)

- small-leaved pussytoes (Antennaria howellii)

- wild columbine (Aquilegia canadensis)

- wormwood (Artemisia campestris)

- harebell (Campanula rotundifolia)

- small blue-eyed Mary (Collinsia parviflora)

- rock whitlow-grass (Draba arabisans)

- prairie cinquefoil (Drymocallis arguta)

- large-leaved aster (Eurybia macrophylla)

- wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana)

- false spikenard (Maianthemum racemosum)

- early saxifrage (Micranthes virginiensis)

- balsam ragwort (Packera paupercula)

- western smartweed (Polygonum douglasii)

- clammy cudweed (Pseudognaphalium macounii)

- three-toothed cinquefoil (Sibbaldiopsis tridentata)

- sand violet (Viola adunca)

Ferns

- maidenhair spleenwort (Asplenium trichomanes)

- male fern (Dryopteris filix-mas)

- common polypody (Polypodium virginianum)

- Braun’s holly-fern (Polystichum braunii)

- northern holly-fern (Polystichum lonchitis)

- rusty woodsia (Woodsia ilvensis)

Fern Allies

- ground-cedar (Diphasiastrum tristachyum)

- sand club moss (Selaginella rupestris)

Shrubs

- serviceberries (Amelanchier spp.)

- bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi)

- New Jersey tea (Ceanothus herbaceus)

- common juniper (Juniperus communis)

- creeping juniper (Juniperus horizontalis)

- choke cherry (Prunus virginiana)

- staghorn sumac (Rhus typhina)

- wild rose (Rosa acicularis)

- soapberry (Shepherdia canadensis)

- snowberry (Symphoricarpos albus)

- low sweet blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium)

Trees

- balsam fir (Abies balsamea)

- red maple (Acer rubrum)

- mountain maple (Acer spicatum)

- juneberry (Amelanchier arborea)

- paper birch (Betula papyrifera)

- white spruce (Picea glauca)

- red pine (Pinus resinosa)

- white pine (Pinus strobus)

- big-toothed aspen (Populus grandidentata)

- red oak (Quercus rubra)

- northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis)

Noteworthy Animals

The steep rock ridges associated with northern bald are important habitat for raptors.

Rare Plants

- Ceanothus sanguineus (redstem ceanothus, state threatened)

- Collinsia parviflora (small blue-eyed Mary, state threatened)

- Dryopteris filix-mas (male fern, state special concern)

- Ranunculus rhomboideus (prairie buttercup, state threatened)

- Ribes oxyacanthoides (northern gooseberry, state special concern)

Rare Animals

- Falco columbarius (merlin, state threatened)

Biodiversity Management Considerations

Because of the thin soils, which cause shallow rooting, and harsh conditions, the vegetation of northern balds can be extremely slow to recover or reestablish following excessive trampling. Trails through balds should be minimized or avoided. Roads and trails also provide routes for invasive plants to establish. Invasive plants that threaten the diversity and community structure of northern balds include spotted knapweed (Centaurea stoebe), ox-eye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare), Canada bluegrass (Poa compressa), sheep sorrel (Rumex acetosella), and hawkweeds (Hieracium spp.). Monitoring and control efforts to detect and remove invasive species are critical to the long-term viability of northern balds. Maintaining a mature, unfragmented forested buffer around balds may help limit the local seed source for invasive species distributed by wind or birds. Use of the escarpments for rock climbing has the potential to degrade vegetation along the cliff edge. Snowmobiling through northern balds also threatens vegetation.

Variation

The northern balds of the Keweenaw Peninsula, located on volcanic conglomerate bedrock, appear to support a more diverse flora than those on basalt to the southwest.

Similar Natural Communities

Granite bedrock glade, volcanic bedrock glade, limestone bedrock glade, granite cliff, limestone cliff, sandstone cliff, and volcanic cliff.

Places to Visit

- Bare Bluffs Bald, Michigan Nature Association (Grinnell Memorial Sanctuary at Bare Bluff), Keweenaw Co.

- Escarpment Trail, Porcupine Mountains Wilderness State Park, Ontonagon Co.

- Isle Royale National Park, Keweenaw Co.

- Mt. Lookout, Brockaway Mountain Drive, Keweenaw Co.

Relevant Literature

- Albert, D.A., P. Comer, D. Cuthrell, D. Hyde, W. MacKinnon, M. Penskar, and M. Rabe. 1997. The Great Lakes bedrock lakeshores of Michigan. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 218 pp.

- Bornhorst, T.J., and W.I. Rose. 1994. Self-guided geological field trip to the Keweenaw Peninsula, Michigan. Proceedings of the Institute on Lake Superior Geology. Volume 40, Part 2. 185 pp.

- Cairns, D.M. 2001. Patterns of winter desiccation in krummholz forms of Abies lasiocarpa at treeline site in Glacier National Park, Montana, USA. Geografiska Annaler. Series A, Physical Geography 83(3): 157-168.

- Dorr, J.A., Jr., and D.F. Eschman. 1970. Geology of Michigan. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI. 470 pp.

- Faber-Langendoen, D., ed. 2001. Plant communities of the Midwest: Classification in an ecological context. Association for Biodiversity Information, Arlington, VA. 61 pp. + appendix (705 pp.).

- Given, D.R., and J.H. Soper. 1981. The arctic-alpine element of the vascular flora at Lake Superior. National Museums of Canada, Publication in Botany 10: 1-70.

- LaBerge, G.L. 1994. Geology of the Lake Superior region. Geoscience Press, Phoenix, AZ. 313 pp.

- Reed, R.C., and J. Daniels. 1987. Bedrock geology of northern Michigan. State of Michigan Department of Natural Resources. Map: 1: 500,000.

- Reschke, C. 1985. Vegetation of the conglomerate rock shoreline of the Keweenaw Peninsula, northern Michigan. M.S. thesis. University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI. 118 pp.

- Slavick, A.D., and R.A. Janke. 1987. The vascular flora of Isle Royale National Park. Michigan Botanist 26: 91-134.

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: January 23, 2026).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.