Patterned Fen

Overview

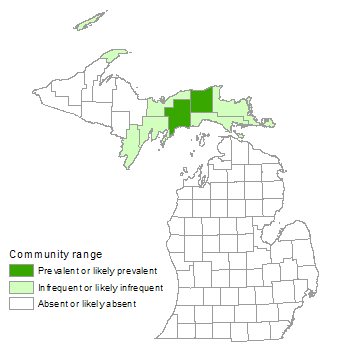

Patterned fen is a minerotrophic shrub- and herb-dominated peatland mosaic characterized by a series of peat ridges (strings) and hollows (flarks) oriented parallel to the slope of the landform and perpendicular to the flow of groundwater. The strings vary in height, width, and spacing, but are generally less than one meter tall, resulting in a faint wave-like pattern that may be discernable only from aerial photographs. The flarks are saturated to inundated open lawns of sphagnum mosses, sedges, and rushes, while the strings are dominated by sedges, shrubs, and scattered, stunted trees. Patterned fens occur in the eastern Upper Peninsula, with the highest concentration found in Schoolcraft County. Patterned fens are also referred to as patterned bogs, patterned peatlands, strangmoor, aapamires, and string bogs.

Rank

Global Rank: GU - Unrankable

State Rank: S2 - Imperiled

Landscape Context

Patterned fens are prominent features in the boreal and sub-boreal regions of North America, Europe, and Siberia. This natural community reaches its southern extent in the Great Lakes States of Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan. Fourteen high-quality patterned fens, totaling approximately 34,000 acres, have been documented in the eastern Upper Peninsula in Alger, Chippewa, Delta, Luce, Mackinac, and Schoolcraft Counties.

Landscapes that support patterned fens exhibit a gradual slope of approximately 2%, or two to twelve feet per mile. Patterned fens are located on expansive, poorly drained sandy glacial lakeplains and broad outwash channels immediately adjacent to glacial lakeplains. Patterned fens occur as part of larger wetland complexes and border other peatland types, especially muskeg. Additional wetland communities associated with patterned fen include poor fen, northern wet meadow, northern shrub thicket, intermittent wetland, and rich conifer swamp. Narrow transverse dune ridges within patterned fen complexes are common and support dry northern forest and dry-mesic northern forest.

Soils

Peat (including fibric, hemic, and sapric peat) forms the substrate for both the strings and flarks of patterned fen communities. Peat can be several meters deep (10 to 25 feet for Lake Agassiz peatlands of Minnesota) and is derived from sedges, sphagnum mosses, reeds, and moderately decomposed woody material. The saturated peat ranges from medium acid to circumneutral. The flarks tend to be wetter, slightly acidic to circumneutral, and more minerotrophic than the strings, although nutrient availability and pH can differ greatly both within and among patterned peatland systems. The amount of water in the flarks also varies depending on local hydrology, precipitation, and season.

Natural Processes

Given the level to gently sloping topography of patterned fens, peat formation and expansion are primarily the result of paludification, the encroachment of sphagnum mosses into adjacent terrestrial systems. The sphagnum mosses responsible for paludification may have originated from nearby peat-filled lake basins or other peat-accumulating depressional wetlands.

Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the subtle dynamics responsible for the patterning within patterned fens. Most researchers agree that the direction of water movement is an essential factor as the strings and flarks are consistently oriented perpendicular to the direction of water flow. Early research suggested that strings and flarks are a result of permafrost and frost action, but patterned peatlands have since been documented in northern Michigan, Minnesota, and southern Wisconsin, where permafrost is absent. Another hypothesis to explain the origin of strings and flarks is the gradual down-slope slipping of peat. In this hypothesis, peat moves downslope until the advancing soil catches on a subsurface irregularity, such as a rock or tree, and stabilizes to form a string, eventually creating a patterning effect across the peatland. Others suggest that the string and flark patterning is the result of gradual expansion and merger of hollows created in sedge hummock-hollow microtopography within the peatland. This process is thought to be controlled by differential rates of peat accumulation and enhanced by active peat degradation within the hollows. Further research is needed to completely understand the complex biotic, chemical, and physical interactions occurring within patterned fens. Additional research on the fire regimes of patterned fens is warranted. During drought years, fire is an important disturbance factor influencing the species composition and structure of patterned fen and also potentially impacting the patterning.

Vegetation

Vegetation of the alternating strings and flarks can differ in species composition and structure. The strings are comprised of slightly raised ridges of peat and are dominated by sedges, forbs, and small shrubs including the following species: sedges (Carex oligosperma, C. sterilis, and C. lasiocarpa), round-leaved sundew (Drosera rotundifolia), royal fern (Osmunda regalis), bog aster (Oclemena nemoralis), bog goldenrod (Solidago uliginosa), pitcher-plant (Sarracenia purpurea), bog birch (Betula pumila), shrubby cinquefoil (Dasiphora fruticosa), bog rosemary (Andromeda glaucophylla), leatherleaf (Chamaedaphne calyculata), black chokeberry (Aronia prunifolia), bog willow (Salix pedicellaris), and bog laurel (Kalmia polifolia). Scattered and stunted trees of black spruce (Picea mariana), northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis), and tamarack (Larix laricina) are also found on the strings but generally cover less than 10% of the area. The flarks consist of level areas or hollows between slightly elevated strings and are dominated by sphagnum mosses, sedges, and rushes including the following species: sphagnum mosses (i.e., Sphagnum angustifolium, S. fuscum, and S. magellanicum), sedges (Carex limosa, C. livida, C. lasiocarpa, and C. exilis), spoon-leaf sundew (Drosera intermedia), white beak-rush (Rhynchospora alba), large cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon), twig-rush (Cladium mariscoides), Canadian rush (Juncus canadensis), water horsetail (Equisetum fluviatile), bog buckbean (Menyanthes trifoliata), arrow-grass (Scheuchzeria palustris), three-way sedge (Dulichium arundinaceum), and flat-leaved bladderwort (Utricularia intermedia). Additional characteristic species of patterned fen include dragon’s mouth (Arethusa bulbosa), sedges (Carex buxbaumii, C. echinata), tufted bulrush (Trichophorum cespitosum), English sundew (Drosera anglica, state special concern), marsh cinquefoil (Comarum palustre), marsh St. John’s-wort (Triadenum fraseri), golden-seeded spike-rush (Eleocharis elliptica), narrow-leaved cotton-grass (Eriophorum angustifolium), and common bog arrow-grass (Triglochin maritima). Linear bands or teardrops of rich conifer swamp and northern shrub thicket commonly occur within patterned fens. In addition, low, narrow dune ridges dominated by pines also characterize patterned peatland landscapes.

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Graminoids

- blue-joint (Calamagrostis canadensis)

- sedges (Carex buxbaumii, C. echinata, C. exilis, C. lasiocarpa, C. limosa, C. livida, C. oligosperma, C. sterilis, and C. stricta)

- twig-rush (Cladium mariscoides)

- three-way sedge (Dulichium arundinaceum)

- golden-seeded spike-rush (Eleocharis elliptica)

- narrow-leaved cotton-grass (Eriophorum angustifolium)

- green-keeled cotton-grass (Eriophorum viridi-carinatum)

- Canadian rush (Juncus canadensis)

- common reed (Phragmites australis subsp. americanus)

- beak-rushes (Rhynchospora alba and R. fusca)

- submergent bulrush (Schoenoplectus subterminalis)

- alpine bulrush (Trichophorum alpinum)

- tufted bulrush (Trichophorum cespitosum)

Forbs

- wood anemone (Anemone quinquefolia)

- dragon’s mouth (Arethusa bulbosa)

- marsh cinquefoil (Comarum palustre)

- flat-topped white aster (Doellingeria umbellata)

- round-leaved sundew (Drosera rotundifolia)

- false mayflower (Maianthemum trifolium)

- bog buckbean (Menyanthes trifoliata)

- bog aster (Oclemena nemoralis)

- rose pogonia (Pogonia ophioglossoides)

- glaucous white lettuce (Prenanthes racemosa)

- round-leaved pyrola (Pyrola americana)

- pitcher-plant (Sarracenia purpurea)

- arrow-grass (Scheuchzeria palustris)

- bog goldenrod (Solidago uliginosa)

- rush aster (Symphyotrichum boreale)

- purple meadow-rue (Thalictrum dasycarpum)

- St. John’s-wort (Triadenum fraseri)

- common bog arrow-grass (Triglochin maritima)

- bladderworts (Utricularia cornuta, U. intermedia, and U. vulgaris)

Ferns

- sensitive fern (Onoclea sensibilis)

- royal fern (Osmunda regalis)

- marsh fern (Thelypteris palustris)

Fern Allies

- water horsetail (Equisetum fluviatile)

Mosses

- ribbed bog moss (Aulacomnium palustre)

- calliergon moss (Calliergon trifarium)

- campylium mosses (Campylium spp.)

- fork mosses (Dicranum spp.)

- haircap mosses (Polytrichum spp.)

- scorpidium moss (Scorpidium scorpioides)

- sphagnum mosses (Sphagnum spp.)

Shrubs

- tag alder (Alnus incana)

- bog rosemary (Andromeda glaucophylla)

- black chokeberry (Aronia prunifolia)

- bog birch (Betula pumila)

- leatherleaf (Chamaedaphne calyculata)

- shrubby cinquefoil (Dasiphora fruticosa)

- mountain holly (Ilex mucronata)

- bog laurel (Kalmia polifolia)

- mountain fly honeysuckle (Lonicera villosa)

- alder-leaved buckthorn (Rhamnus alnifolia)

- Labrador-tea (Rhododendron groenlandicum)

- dwarf raspberry (Rubus acaulis)

- bog willow (Salix pedicellaris)

- blueberries (Vaccinium angustifolium and V. myrtilloides)

- cranberries (Vaccinium macrocarpon and V. oxycoccos)

Trees

- tamarack (Larix laricina)

- black spruce (Picea mariana)

- white pine (Pinus strobus)

- northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis)

Noteworthy Animals

Beaver can build dams on streams that drain patterned fen, raising water levels and killing trees and other plants not able to tolerate rising water levels or adapted to prolonged flooding. Tree survival is also limited by insects and parasites. Insect outbreaks of larch sawfly (Pristiphora erichsonii) cause heavy mortality of tamarack, while the plant parasite dwarf mistletoe (Arceuthobium pusillum) kills black spruce.

Rare Plants

- Amerorchis rotundifolia (round-leaved orchis, state endangered)

- Bartonia paniculata (panicled screw-stem, state threatened)

- Carex heleonastes (Hudson Bay sedge, state endangered)

- Carex novae-angliae (New England sedge, state threatened)

- Drosera anglica (English sundew, state special concern)

- Juncus stygius (Moor rush, state threatened)

- Petasites sagittatus (sweet coltsfoot, state threatened)

- Rubus acaulis (dwarf raspberry, state endangered)

Rare Animals

- Alces alces (moose, state threatened)

- Boloria freija (Freija fritillary, state special concern)

- Boloria frigga (Frigga fritillary, state special concern)

- Canis lupus (gray wolf, state threatened)

- Circus cyaneus (northern harrier, state special concern)

- Emydoidea blandingii (Blanding’s turtle, state special concern)

- Erebia discoidalis (red-disked alpine, state special concern)

- Falcipennis canadensis (spruce grouse, state special concern)

- Falco columbarius (merlin, state threatened)

- Somatochlora hineana (Hine’s emerald, federal/state endangered)

- Somatochlora incurvata (incurvate emerald, state special concern)

- Williamsonia fletcheri (ebony boghaunter, state special concern)

Biodiversity Management Considerations

A major threat to patterned fen is hydrologic alteration through ditching, damming, logging, and trail- and road-building activities, which can result in significant changes to peatland composition and structure. Peat mining also threatens pristine peatland systems. Effective conservation of patterned peatlands should include protecting and/or restoring the natural hydrology of the peatland and surrounding watershed.

Monitoring and control efforts to detect and remove invasive species before they become widespread are critical to the long-term viability of patterned fen. Invasive species that may threaten diversity and community structure of patterned fen include glossy buckthorn (Frangula alnus), multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora), purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), narrow-leaved cat-tail (Typha angustifolia), hybrid cat-tail (Typha xglauca), reed canary grass (Phalaris arundinacea), and reed (Phragmites australis subsp. australis).

Variation

Vegetation and patterning can vary significantly within and among patterned fens and is influenced by groundwater flow and past disturbances events such as fire and flooding.

Similar Natural Communities

Northern fen, coastal fen, poor fen, northern wet meadow, northern shrub thicket, muskeg, rich conifer swamp, and poor conifer swamp.

Places to Visit

- Black Creek (Tokar's Patterned Fen), Newberry State Forest Management Unit, Chippewa Co.

- Creighton Marsh, Shingleton State Forest Management Unit, Schoolcraft Co.

- Marsh Creek (Seney Strangmoor), Seney National Wildlife Refuge and Shingleton State Forest Management Unit, Schoolcraft Co.

- McMahon Lake, Newberry State Forest Management Unit and The Nature Conservancy (McMahon Lake Preserve), Luce Co.

- Park Patterned Peatland, Tahquamenon Falls State Park, Chippewa Co.

- Sleeper Lake, Newberry State Forest Management Unit and The Nature Conservancy (McMahon Lake Preserve), Luce Co.

Relevant Literature

- Curtis, J.T. 1959. The vegetation of Wisconsin. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, WI. 657 pp.

- Faber-Langendoen, D., ed. 2001. Plant communities of the Midwest: Classification in an ecological context. Association for Biodiversity Information, Arlington, VA. 61 pp. + appendix (705 pp.).

- Foster, D.R., and G.A. King. 1984. Landscape features, vegetation and developmental history of a patterned fen in south-eastern Labrador, Canada. Journal of Ecology 72(1): 115-143.

- Gates, F.C. 1942. The bogs of northern Lower Michigan. Ecological Monographs 12(3): 213-254.

- Glaser, P.H., G.A. Wheeler, E. Gorham, and H.E. Wright, Jr. 1981. The patterned mires of the Red Lake Peatland, northern Minnesota: Vegetation, water chemistry and landforms. Journal of Ecology 69(2): 575-599.

- Grittinger, T. 1970. String bog in southern Wisconsin. Ecology 51(5): 928-930.

- Heinselman, M.L. 1963. Forest sites, bog processes, and peatland types in the Glacial Lake Agassiz Region, Minnesota. Ecological Monographs 33(4): 327-374.

- Heinselman, M.L. 1965. String bogs and other patterned organic terrain near Seney, Upper Michigan. Ecology 46 (1/2): 185-188.

- Heinselman, M.L. 1970. Landscape evolution, peatland types, and the environment in the Lake Agassiz Peatlands Natural Area, Minnesota. Ecological Monographs 40(2): 235-261.

- Miller, N.G., and R.P. Futyma. 1987. Paleohydrological implications of Holocene peatland development in northern Michigan. Quaternary Research 27: 297-311.

- Wright, H.E., Jr., B.A. Coffin, and N.A. Aaseng. 1992. The patterned peatlands of Minnesota. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, MN. 327 pp.

For a full list of references used to create this description, please refer to the natural community abstract for Patterned Fen.

More Information

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: February 26, 2026).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.