Sand and Gravel Beach

Overview

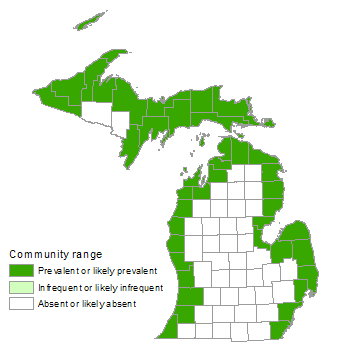

Sand and gravel beaches occur along the shorelines of the Great Lakes and on some of Michigan’s larger freshwater lakes, where wind, waves, and winter ice cause the shoreline to be too unstable to support aquatic vegetation. Because of the high levels of disturbance, these beaches are typically quite open, with sand and gravel sediments and little or no vegetation.

Rank

Global Rank: G3? - Vulnerable (inexact)

State Rank: S3 - Vulnerable

Landscape Context

Sand and gravel beaches occur along the shorelines of the Great Lakes and on some of Michigan’s larger freshwater lakes, where the energy from waves and ice abrasion are adequate to maintain an open beach. Natural communities occurring adjacent to sand and gravel beach include open dunes, interdunal wetlands, wooded dune and swale complex, cobble shore, bedrock lakeshore, and lakeshore cliffs.

Soils

The dynamic nature of open sand and gravel beaches greatly inhibits soil development. Uprooted trees accumulate on some beaches, fostering localized sand accretion and often vegetation establishment. Finer organic material also builds up seasonally on beaches, and can include plant debris, algae, and dead lake or wetland organisms such as insects, fish, and zebra mussels (Dreissena polymorpha), a small invasive bivalve mussel. These aggregations can be large, greatly increasing the nutrient availability and changing the sediment characteristics of the beach, although these changes are often temporary due to the dynamics of the shoreline environment. Storm waves and winter ice typically prevent permanent vegetation establishment and soil development. Where organic sediments are protected from erosive forces, vegetation can establish, stabilize the shoreline, and thus eliminate portions of the open beach.

Natural Processes

The openness of beach vegetation is the result of the unstable sediment conditions caused by wind, waves, and winter ice. Beaches tend to accumulate sand during less windy spring and summer periods, and lose sand through erosion during strong fall and winter storms. Gravel movement along the shoreline is generated completely by wave or ice movement, while sand can also be moved by wind after its deposition on the beach, often leading to dune development farther inland. While many species of plants are able to establish on sand or gravel beaches, the extreme conditions of desiccation and erosion allow few species to reach maturity and set seed. Severity of desiccation increases as particle size increases, but on many gravel beaches vegetation can establish because finer particles of sand are trapped among the gravel. On sand beaches, successful vegetation establishment causes an increase in surface roughness, slowing both the wind and movement of sand, and resulting in the accumulation of sand in the form of coastal dunes. Vegetation cover increases with distance from the water’s edge due to decreasing levels of erosive wind and water energy. Because water levels fluctuate on many lakes, vegetation cover can increase during periods of low water. Sand beaches regularly migrate with changing water levels and shoreline configuration.

Vegetation

Sand and gravel beach is characterized by both a low diversity of plant species and low levels of plant cover. A wide variety of plants can develop at the inland margin of sand and gravel beaches, but few establish and persist on the active beach, where there is often intense wind and wave action, resulting in almost constantly moving sand. Among the few species able to survive the dynamic beach zone are sea rocket (Cakile edentula), seaside spurge (Euphorbia polygonifolia), Baltic rush (Juncus balticus), silverweed (Potentilla anserina), beach pea (Lathyrus japonicus), and marram grass (Ammophila breviligulata). The rare Great Lakes endemic Pitcher’s thistle (Cirsium pitcheri, federal/state threatened) occasionally establishes on active sand beaches during low-water periods. The community typically contains a zone of open sand along the water’s edge, with only scattered stems of the above-mentioned species. Farther from the water, marram grass is able to stabilize the sand with its extensive roots and rhizomes, allowing for the accumulation of sand into a beach ridge above the zone of active waves. Many more plant species can survive in this zone of sand accumulation, including many herbs, shrubs, and tree seedlings and saplings.

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Graminoids

- marram grass (Ammophila breviligulata)

- Baltic rush (Juncus balticus)

- hardstem bulrush (Schoenoplectus acutus)

- threesquare (Schoenoplectus pungens)

Forbs

- sea rocket (Cakile edentula)

- Pitcher’s thistle (Cirsium pitcheri)

- bugseeds (Corispermum americanum and C. pallasii)

- seaside spurge (Euphorbia polygonifolia)

- beach pea (Lathyrus japonicus)

- silverweed (Potentilla anserina)

- Lake Huron tansy (Tanacetum bipinnatum)

Shrubs

- sand dune willow (Salix cordata)

- sandbar willow (Salix exigua)

- blue-leaf willow (Salix myricoides)

Noteworthy Animals

Sand beaches are favorite feeding grounds for shorebirds. Insects, birds, and other fauna feed intensively on dead and decomposing organic materials that accumulate along the shoreline. Large numbers of aquatic insects, such as midges, live in the sediments and provide important food for migratory songbirds during spring migration. In addition, butterflies often gather on the beach for moisture and nutrients during migration. Gravel beaches, especially on islands, are used by nesting gulls, terns, cormorants, and other waterbirds.

Rare Plants

- Adlumia fungosa (climbing fumitory, state special concern)

- Beckmannia syzigachne (slough grass, state threatened)

- Calamagrostis lacustris (northern reedgrass, state threatened)

- Cirsium pitcheri (Pitcher’s thistle, federal/state threatened)

- Elymus mollis (American dune wild-rye, state special concern)

- Iris lacustris (dwarf lake iris, federal/state threatened)

- Listera auriculata (auricled twayblade, state threatened)

- Polygonum viviparum (alpine bistort, state threatened)

- Potentilla paradoxa (sand cinquefoil, state threatened)

- Salix pellita (satiny willow, state special concern)

- Senecio congestus (marsh-fleabane, presumed extirpated from Michigan)

- Sisyrinchium hastile (blue-eyed-grass, presumed extirpated from Michigan)

- Tanacetum huronense (Lake Huron tansy, state threatened)

Rare Animals

- Charadrius melodus (piping plover, federal/state endangered)

- Trimerotropis huroniana (Lake Huron locust, state threatened)

Biodiversity Management Considerations

Off-road vehicles can destabilize beach areas, especially those areas farther from the shore where vegetation is becoming stabilized. Eliminating illegal off-road vehicle activity is a primary means of protecting the ecological integrity of sand and gravel beaches. Raccoons and unleashed dogs are a major threat to piping plovers, and high levels of human visitation to plover beaches can also result in low breeding success. Many parks actively maintain open beach conditions by mechanical grooming, eliminating the natural flora and fauna of the beach.

Variation

There is considerable variability in sand and gravel, based on the rock from which the sands and gravels formed. In portions of the Keweenaw Peninsula, sand-sized mine wastes form broad beaches of dark sand, especially along the Portage Shipping Canal, but because of their anthropogenic origin, these areas are not considered a natural community.

Similar Natural Communities

Open dunes, limestone cobble shore, sandstone cobble shore, volcanic cobble shore, and wooded dune and swale complex.

Places to Visit

- Little Presque Isle, Gwinn State Forest Management Unit, Marquette Co.

- Nordhouse Dunes, Ludington State Park and Manistee National Forest, Mason Co.

- Pictured Rocks, Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore, Alger Co.

- Sleeping Bear Dunes, Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, Leelanau Co.

- Sleeping Misery Bay, Baraga State Forest Management Unit, Ontonagon Co.

- South Manitou Island, Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, Leelanau Co.

- Twelve Mile Beach, Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore, Alger Co.

Relevant Literature

- Albert, D.A. 2007. Natural community abstract for sand and gravel beach. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 7 pp.

- Faber-Langendoen, D., ed. 2001. Plant communities of the Midwest: Classification in an ecological context. Association for Biodiversity Information, Arlington, VA. 61 pp. + appendix (705 pp.).

- Komar, P.D. 1976. Beach processes and sedimentation. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. 544 pp.

- Mackey, S.D., and D.L. Liebenthal. 2005. Mapping changes in Great Lakes nearshore substrate distributions. Journal of Great Lakes Research 32 (Supplement 1): 75-89.

- Packham, J.R., and A.J. Willis. 1997. Ecology of dunes, salt marsh and shingle. Chapman & Hall, London, UK. 331 pp.

- Ritter, D.F., R.C. Kochel, and J.R. Miller. 1995. Process geomorphology. Third Edition. William C. Brown, Dubuque, IA. 546 pp.

For a full list of references used to create this description, please refer to the natural community abstract for Sand and Gravel Beach.

More Information

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: January 24, 2025).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.