Dry-mesic Prairie

Overview

Dry-mesic prairie is a native grassland community dominated by big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), and Indian grass (Sorghastrum nutans). The community occurs on sandy loam or loamy sand on level to gently sloping sites of glacial outwash, coarse-textured end moraines, and glacial till plain. The community represents the stands of open grassland that occurred in association with historic oak openings throughout much of southern Lower Michigan. In previous versions of the natural community classification this community was called woodland prairie.

Rank

Global Rank: G3 - Vulnerable

State Rank: S1 - Critically imperiled

Landscape Context

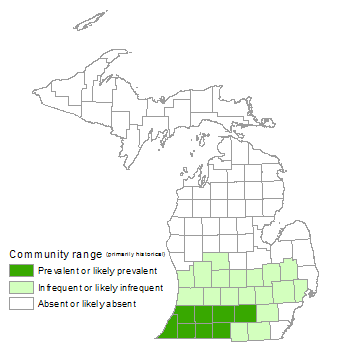

Dry-mesic prairie occurs primarily on level to gently sloping sites of glacial outwash or coarse-textured end moraines. Historically, the majority of dry-mesic prairies occurred within oak openings in the Kalamazoo Interlobate Subsection and may have graded into mesic prairie and bur oak plains on level outwash plains such as the Battlecreek Outwash Plain. Today, the community is almost entirely restricted to railroad right-of-ways, which typically border agricultural fields.

Soils

Soils are typically strongly acid to circumneutral sandy loam or occasionally loamy sand with moderate water-retaining capacity.

Natural Processes

Fire played a critical role in creating and maintaining the open conditions of Michigan prairie and oak savanna ecosystems. Fire maintains species diversity by promoting seed germination, creating microsites for seedling establishment, and releasing and recycling important plant nutrients. In the absence of frequent fires, which suppress woody vegetation, Michigan’s prairies and open oak ecosystems (e.g., oak openings, bur oak plains, oak barrens, and oak woodlands) are quickly colonized by trees and shrubs and convert to oak forests.

While occasional lightning strikes resulted in landscape-scale fires, Native Americans were the main source of ignition prior to European settlement. Native Americans intentionally set fires to clear brush, make land more passable, increase productivity of berry crops and agricultural fields, and improve hunting. The frequency and intensity of historical fires varied depending on the type and volume of fuel, topography, presence of natural firebreaks, and density of Native Americans. Carried by wind, landscape-scale fires moved across outwash plains and up slopes of end moraines and ground moraines, converting oak forests into dry-mesic prairies and oak openings.

Vegetation

Unfortunately, no detailed ecological study of dry-mesic prairie was completed in Michigan before the nearly total demise of the community. What information is available comes from written descriptions of the community by early European settlers and from studies of small prairie remnants in Michigan and Wisconsin. Dry-mesic prairie supports a dense to moderately dense growth of low- to medium-height herbaceous vegetation with very little bare ground. The community is dominated by big bluestem, little bluestem, and Indian grass, which may vary in relative dominance. Species that reach their greatest abundance in dry-mesic prairie in Michigan include leadplant (Amorpha canescens, state special concern), thimbleweed (Anemone cylindrica), butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosa), smooth aster (Symphyotrichum laeve), and daisy fleabane (Erigeron strigosus). Grubs of white oak (Quercus alba), black oak (Q. velutina), and bur oak (Q. macrocarpa), which were maintained in a shrub-like condition as a result of annual fires, were abundant in dry-mesic prairie, as were widely scattered, open grown adults of these same species, especially white oak. In addition to the species mentioned above, other common plants of Michigan dry-mesic prairie include Pennsylvania sedge (Carex pensylvanica), bastard toadflax (Comandra umbellata), round-headed bush clover (Lespedeza capitata), wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana), wild bergamot (Monarda fistulosa), northern dewberry (Rubus flagellaris), black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta), old field goldenrod (Solidago nemoralis), spiderwort (Tradescantia ohiensis), and pasture rose (Rosa carolina).

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Graminoids

- big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii)

- Bicknell’s sedge (Carex bicknellii)

- Pennsylvania sedge (Carex pensylvanica)

- little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium)

- Indian grass (Sorghastrum nutans)

Forbs

- thimbleweed (Anemone cylindrica)

- smooth pussytoes (Antennaria parlinii)

- pale Indian plantain (Arnoglossum atriplicifolium)

- milkweeds (Asclepias purpurascens, A. syriaca, A. tuberosa, A. verticillata, A. viridiflora, and others)

- white false indigo (Baptisia lactea)

- false boneset (Brickellia eupatorioides)

- bastard-toadflax (Comandra umbellata)

- prairie coreopsis (Coreopsis palmata)

- tall coreopsis (Coreopsis tripteris)

- tick-trefoils (Desmodium canadense, D. illinoense, and D. marilandicum)

- daisy fleabanes (Erigeron annuus and E. strigosus)

- flowering spurge (Euphorbia corollata)

- wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana)

- American columbo (Frasera caroliniensis)

- western sunflower (Helianthus occidentalis)

- tall lettuce (Lactuca canadensis)

- round-headed bush-clover (Lespedeza capitata)

- hairy bush-clover (Lespedeza hirta)

- hoary puccoon (Lithospermum canescens)

- false spikenard (Maianthemum racemosum)

- wild bergamot (Monarda fistulosa)

- Solomon-seal (Polygonatum biflorum)

- old-field cinquefoil (Potentilla simplex)

- yellow coneflower (Ratibida pinnata)

- black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta)

- goldenrods (Solidago juncea, S. nemoralis, S. rigida, and S. speciosa)

- asters (Symphyotrichum laeve, S. oolentangiense, and S. pilosum)

- yellow-pimpernel (Taenidia integerrima)

- spiderwort (Tradescantia ohiensis)

- Culver’s-root (Veronicastrum virginicum)

Shrubs

- leadplant (Amorpha canescens)

- New Jersey tea (Ceanothus americanus)

- American hazelnut (Corylus americana)

- winged sumac (Rhus copallina)

- smooth sumac (Rhus glabra)

- pasture rose (Rosa carolina)

- northern dewberry (Rubus flagellaris)

- prairie willow (Salix humilis)

Trees

- white oak (Quercus alba)

- bur oak (Quercus macrocarpa)

- dwarf chinquapin oak (Quercus prinoides)

- black oak (Quercus velutina)

Noteworthy Animals

Ants, particularly the genus Formica, play an important role in mixing and aerating prairie soils as they continually build and abandon mounds, overturning large portions of soil in the process. Other important species contributing to soil mixing and aeration include moles, mice, skunks, and badgers. Historically, large herbivores such as bison likely significantly influenced plant species diversity in prairie and oak savanna ecosystems. Bison selectively forage on grasses and sedges, thereby reducing the dominance of graminoids and providing a competitive advantage to forb species. Additionally, bison wallowing and trampling promotes plant species diversity by creating microsites for seed germination and seedling establishment and reducing the dominance of robust perennials.

Rare Plants

- Amorpha canescens (leadplant, state special concern)

- Baptisia lactea (white false indigo, state special concern)

- Cirsium hillii (Hill’s thistle, state special concern)

- Coreopsis palmata (prairie coreopsis, state threatened)

- Echinacea purpurea (purple coneflower, presumed extirpated from Michigan)

- Gentiana flavida (white gentian, state endangered)

- Helianthus microcephalus (small wood sunflower, presumed extirpated from Michigan)

- Houstonia caerulea (bluets, state special concern)

- Onosmodium molle (marbleweed, presumed extirpated from Michigan)

- Oxalis violacea (violet wood-sorrel, state threatened)

- Panicum leibergii (Leiberg’s panic grass, state threatened)

- Pycnanthemum pilosum (hairy mountain-mint, state threatened)

- Rudbeckia subtomentosa (sweet coneflower, presumed extirpated from Michigan)

- Scleria triglomerata (tall nut-rush, state special concern)

- Silphium integrifolium (rosinweed, state threatened)

- Viola pedatifida (prairie birdfoot violet, state threatened)

Rare Animals

- Ammodramus henslowii (Henslow’s sparrow, state special concern)

- Ammodramus savannarum (grasshopper sparrow, state special concern)

- Asio flammeus (short-eared owl, state special concern)

- Asio otus (long-eared owl, state threatened)

- Circus cyaneus (northern harrier, state special concern)

- Clemmys guttata (spotted turtle, state threatened)

- Clonophis kirtlandii (Kirtland’s snake, state threatened)

- Elaphe o. obsoleta (black rat snake, state special concern)

- Emydoidea blandingii (Blanding’s turtle, state special concern)

- Lanius ludovicianus migrans (migrant loggerhead shrike, state endangered)

- Microtus ochrogaster (prairie vole, state endangered)

- Oecanthus pini (pinetree cricket, federal/state endangered)

- Papaipema beeriana (blazing star borer, state special concern)

- Prosapia ignipectus (red-legged spittlebug, state special concern)

- Pygarctia spraguei (Sprague’s pygarctia, state special concern)

- Schinia indiana (phlox moth, state special concern)

- Schinia lucens (leadplant flower moth, state endangered)

- Sistrurus c. catenatus (eastern massasauga, federal candidate species and state special concern)

- Speyeria idalia (regal fritillary, state endangered)

- Spiza americana (dickcissel, state special concern)

- Sturnella neglecta (western meadowlark, state special concern)

- Terrapene c. carolina (eastern box turtle, state special concern)

- Tyto alba (barn owl, state endangered)

Biodiversity Management Considerations

Priorities for conservation of dry-mesic prairie include identifying, protecting, and managing existing remnants where they occur. Several studies to identify prairie remnants in Michigan have been undertaken and most remnants are very small and/or occur as narrow strips adjacent to railroads and agricultural fields. The small size and poor landscape context of most remnant dry-mesic prairies make large-scale restoration of existing prairies nearly impossible. Restoration efforts for dry-mesic prairie should include establishing the community on appropriate sites within the former range of oak openings in southern Lower Michigan. Many suitable sites now support closed-canopy oak forest with understories and canopy trees of red maple. While restoring the matrix community to oak openings, land managers can also establish larger openings with species composition representative of dry-mesic prairie. Reintroducing fire on a frequent or annual basis, along with removing red maple and other mesophytic and invasive tree and shrub species within the former oak openings, will be important management steps in restoring dry-mesic prairie in southern Lower Michigan.

Restoring and managing dry-mesic prairie require frequent prescribed burning to protect and enhance plant species diversity, prevent encroachment of trees and tall shrubs, and control invasive species. Brush cutting accompanied by stump application of herbicide can also be an important component of prairie restoration. To reduce the impacts of management on fire-intolerant species it is important to consider a rotating schedule of prescribed burning in which adjacent management units are burned in alternate years. Alternating burn units provides refugia for fire-intolerant insect species that are then able to recolonize the burned areas. Avian species diversity can also be enhanced by managing large areas as a mosaic of burned and unburned patches. In addition, most restoration sites will require the reintroduction of appropriate native species and genotypes as plant populations at small, isolated prairie remnants may have suffered from reduced gene flow.

Monitoring and control efforts to detect and remove invasive species are critical to the long-term viability of dry-mesic prairie. Invasive species that threaten the diversity and community structure include common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica), autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata), Eurasian honeysuckles (especially Lonicera morrowii, L. tatarica, and L. xbella), multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora), spotted knapweed (Centaurea stoebe), common St. John’s-wort (Hypericum perforatum), ox-eye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare), hawkweeds (Hieracium spp.), hoary alyssum (Berteroa incana), white sweet-clover (Melilotus alba), yellow sweet clover (M. officinalis), leafy spurge (Euphorbia virgata), wild parsnip (Pastinaca sativa), bouncing bet (Saponaria officinalis), Canada bluegrass (Poa compressa), Kentucky bluegrass (P. pratensis), smooth brome (Bromus inermis), and timothy (Phleum pratense).

Variation

Similar Natural Communities

Oak openings, dry sand prairie, hillside prairie, mesic sand prairie, oak barrens, bur oak plains, and mesic prairie.

Places to Visit

- Foster Prairie, City of Ann Arbor, Washtenaw Co.

- Sauk Indian Trail Plant Preserve, Michigan Nature Association, St. Joseph Co.

Relevant Literature

- Albert, D.A. 1995. Regional landscape ecosystems of Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin: A working map and classification. USDA, Forest Service, North Central Forest Experiment Station, St. Paul, MN.

- Chapman, K.A. 1984. An ecological investigation of native grassland in southern Lower Michigan. M.S. thesis, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, MI. 235 pp.

- Curtis, J.T. 1959. The vegetation of Wisconsin. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, WI. 657 pp.

- Kost, M.A. 2004. Natural community abstract for dry-mesic woodland prairie. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 8 pp.

- Faber-Langendoen, D., ed. 2001. Plant communities of the Midwest: Classification in an ecological context. Association for Biodiversity Information, Arlington, VA. 61 pp. + appendix (705 pp.).

- Herkert, J.R., R.E. Szafoni, V.M. Kleen, and J.E. Schwegman. 1993. Habitat establishment, enhancement and management for forest and grassland birds in Illinois. Division of Natural Heritage, Illinois Department of Conservation, Natural Heritage Technical Publication #1, Springfield, IL. 20 pp.

- Panzer, R.D., D. Stillwaugh, R. Gnaedinger, and G. Derkowitz. 1995. Prevalence of remnant dependence among prairie- and savanna-inhabiting insects of the Chicago region. Natural Areas Journal 15: 101-116.

- Scharrer, E.M. 1972. Relict prairie flora of southwestern Michigan. Pp. 9-12 in Proceedings of the Second Midwest Prairie Conference, ed. J.H. Zimmerman. Madison, WI. 242 pp.

- Steuter, A.A. 1997. Bison. Pp. 339-347 in The tallgrass restoration handbook for prairies savannas and woodlands, ed. S. Packard, and C.F. Mutel. Island Press, Washington D.C. 463 pp.

- Thompson, P.W. 1970. The preservation of prairie stands in Michigan. Pp. 13-14 in Proceedings of the Second Midwest Prairie Conference, ed. J.H. Zimmerman. Madison, WI. 242 pp.

- Thompson, P.W. 1975. The floristic composition of prairie stands in southern Michigan. Pp. 317-331 in Prairie: A multiple view, ed. M.K. Wali. The University of North Dakota, Grand Fork, N.D. 433 pp.

- Thompson, P.W. 1983. Composition of prairie stands in southern Michigan and adjoining areas. Pp. 105-111 in Proceedings of the Eighth North American Prairie Conference, ed. R. Brewer. Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, MI.175 pp.

- Trager, J.C. 1990. Restored prairies colonized by native prairie ants (Missouri, Illinois). Restoration and Management Notes 8: 104-105.

For a full list of references used to create this description, please refer to the natural community abstract for Dry-mesic Prairie.

More Information

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: January 27, 2026).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.