Oak Openings

Overview

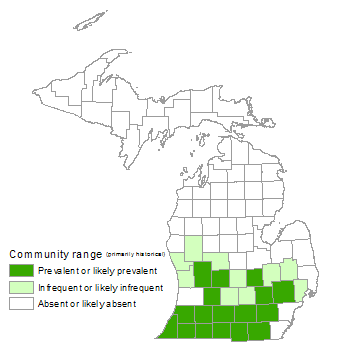

Oak openings are fire-dependent savannas dominated by oaks, having between 10 and 60% canopy, with or without a shrub layer. The predominantly graminoid ground layer is composed of species associated with both prairie and forest communities. Oak openings are found on dry-mesic loams in the southern Lower Peninsula, typically occurring on level to rolling topography of outwash and coarse-textured end moraines. Oak openings have been nearly extirpated from Michigan; only one small example remains. They are known primarily from historical literature and data derived from severely disturbed sites.

Rank

Global Rank: G1 - Critically imperiled

State Rank: S1 - Critically imperiled

Landscape Context

Oak openings occurred in the southern Lower Peninsula primarily on level to rolling topography of glacial outwash plains and coarse-textured end moraines and occasionally on steep slopes of ice-contact features. They were most prevalent on the western side of major firebreaks such as rivers. Oak openings and associated dry-mesic prairie once occurred adjacent to more mesic communities, such as bur oak plains, mesic prairie, and wet-mesic prairie and also likely graded into oak barrens, a drier savanna type, as well as dry-mesic southern forest and dry southern forest. Historically, oak openings occurred in a complex, shifting mosaic of upland and wetland plant communities that depended on frequent fire for maintaining open and semi-open conditions.

Soils

Soils of oak openings are well-drained, moderately fertile, sandy loams, or loams with slightly acid to neutral pH and low to moderate water-retaining capacity.

Natural Processes

Repeated low-intensity fires, working in concert with drought and windthrow, maintained open conditions in oak savanna ecosystems. Within dry-mesic savanna systems, such as oak openings, it is likely that annual or nearly annual fire disturbance was the primary abiotic factor influencing savanna structure and composition. Oak openings were found primarily on level to undulating topography, a landscape in which fires occurred frequently and spread rapidly and evenly. Fires prevented canopy closure and limited the dominance of woody vegetation. Oak savanna and prairie fires occur during the spring, late summer, and fall. Flammability peaks in the spring before grass and forb growth resumes and then again in the late summer and autumn after the above-ground biomass dies back.

Numerous biotic factors influence the patterning of vegetation of oak savannas. In addition to widely distributed overstory trees, savannas are characterized by scattered ant mounds. Mound-building ants play a crucial role in the soil development of prairies and savannas; ants mix and aerate the soil as they build tunnels and bring soil particles and nutrients to the topsoil from lower soil horizons. Herbivores can limit woody establishment and encroachment. With their flammable properties, grasses and forbs help maintain the annual fire regime. Open canopy conditions are also preserved by the development of dense herbaceous litter, which limits tree seedling establishment. Overstory trees influence vegetative composition by affecting the distribution of nutrients, light, and moisture.

Vegetation

Oak openings were described by Michigan settlers as park-like savannas of widely spaced mature oaks, with a wide range of shrub cover above the forb and graminoid ground layer. The broad-crowned, scattered oaks were typically of the same age cohort and the canopy layer generally varied from 10 to 60% cover. The canopy was dominated by white oak (Quercus alba) with codominants including bur oak (Q. macrocarpa) and chinquapin oak (Q. muehlenbergii). Important canopy associates included pignut hickory (Carya glabra), shagbark hickory (C. ovata), red oak (Q. rubra), and black oak (Q. velutina). Oaks, especially black oak, although widely dispersed in the oak openings, were limited to fire-suppressed grubs that often reached just over a meter tall. Scattered or clumped shrubs ranged from 0 to 50% cover depending on fire frequency. The most common shrubs were fire-tolerant species such as American hazelnut (Corylus americana), New Jersey tea (Ceanothus americanus), and leadplant (Amorpha canescens, state special concern). Shrubs such as gray dogwood (Cornus foemina), wild plum (Prunus americana), and smooth sumac (Rhus glabra) occasionally formed thickets in fire-protected microsites. Oak openings were characterized by a discontinuous layer of trees and shrubs and a continuous herbaceous layer. The flora of savannas were a mixture of prairie and forest species, with prairie forbs and grasses more abundant in open areas and forest forbs and woody species more common in shaded areas. Many of the species of oak savanna were, in fact, savanna specialists that thrived in the mottled light conditions provided by the scattered oak canopy. The ground layer of these systems was dominated by a diverse array of graminoids and forbs. Common grasses included big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), and Indian grass (Sorghastrum nutans). Prevalent forbs included hog peanut (Amphicarpaea bracteata), thimbleweed (Anemone cylindrica), purple milkweed (Asclepias purpurascens, state threatened), butterfly-weed (A. tuberosa), false boneset (Brickellia eupatorioides, state special concern), prairie coreopsis (Coreopsis palmata, state threatened), showy tick-trefoil (Desmodium canadense), upland boneset (Eupatorium sessilifolium, state threatened), daisy fleabane (Erigeron strigosus), flowering spurge (Euphorbia corollata), northern bedstraw (Galium boreale), white gentian (Gentiana alba, state endangered), veiny pea (Lathyrus venosus), bush clovers (Lespedeza capitata and L. hirta), wild-bergamot (Monarda fistulosa), Virginia mountain mint (Pycnanthemum virginianum), black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta), starry campion (Silene stellata, state threatened), early goldenrod (Solidago juncea), smooth aster (Symphyotrichum laeve), frost aster (S. pilosum), yellow pimpernel (Taenidia integerrima), feverwort (Triosteum perfoliatum), Culver’s root (Veronicastrum virginicum), and golden alexanders (Zizia aurea).

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Graminoids

- big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii)

- sedges (Carex bicknellii, C. brevior, C.meadii, and others)

- panic grasses (Dichanthelium spp.)

- porcupine grass (Hesperostipa spartea)

- switch grass (Panicum virgatum)

- little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium)

- Indian grass (Sorghastrum nutans)

Forbs

- hog-peanut (Amphicarpaea bracteata)

- thimbleweed (Anemone cylindrica)

- pussytoes (Antennaria howellii and A. parlinii)

- spreading dogbane (Apocynum androsaemifolium)

- pale Indian plantain (Arnoglossum atriplicifolium)

- milkweeds (Asclepias purpurascens, A. syriaca, A. tuberosa, A. verticillata, and A. viridiflora)

- white false indigo (Baptisia lactea)

- false boneset (Brickellia eupatorioides)

- bastard-toadflax (Comandra umbellata)

- prairie coreopsis (Coreopsis palmata)

- tall coreopsis (Coreopsis tripteris)

- tick-trefoils (Desmodium spp.)

- daisy fleabane (Erigeron strigosus)

- upland boneset (Eupatorium sessilifolium)

- flowering spurge (Euphorbia corollata)

- wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana)

- American columbo (Frasera caroliniensis)

- northern bedstraw (Galium boreale)

- white gentian (Gentiana alba)

- wild geranium (Geranium maculatum)

- woodland sunflower (Helianthus divaricatus)

- western sunflower (Helianthus occidentalis)

- pale-leaved sunflower (Helianthus strumosus)

- veiny pea (Lathyrus venosus)

- bush-clovers (Lespedeza capitata, L. frutescens, L. hirta, L. violacea, and L. virginica)

- hoary puccoon (Lithospermum canescens)

- wild lupine (Lupinus perennis)

- false spikenard (Maianthemum racemosum)

- wild-bergamot (Monarda fistulosa)

- wood-betony (Pedicularis canadensis)

- prairie phlox (Phlox pilosa)

- Solomon-seal (Polygonatum biflorum)

- common mountain mint (Pycnanthemum virginianum)

- early buttercup (Ranunculus fascicularis)

- yellow coneflower (Ratibida pinnata)

- black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta)

- starry campion (Silene stellata)

- goldenrods (Solidago caesia, S. juncea, S. nemoralis, S. rigida, and S. speciosa)

- asters (Symphyotrichum laeve, S. oolentangiense, and S. pilosum)

- yellow pimpernel (Taenidia integerrima)

- feverwort (Triosteum perfoliatum)

- Culver’s root (Veronicastrum virginicum)

- American vetch (Vicia americana)

- pale vetch (Vicia caroliniana)

- golden alexanders (Zizia aurea)

Ferns

- bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum)

Woody Vines

- Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia)

- bristly greenbrier (Smilax hispida)

- poison-ivy (Toxicodendron radicans)

- summer grape (Vitis aestivalis)

- riverbank grape (Vitis riparia)

Shrubs

- leadplant (Amorpha canescens)

- New Jersey tea (Ceanothus americanus)

- gray dogwood (Cornus foemina)

- American hazelnut (Corylus americana)

- American plum (Prunus americana)

- pasture rose (Rosa carolina)

- northern dewberry (Rubus flagellaris)

- sumacs (Rhus copallina, R. glabra, and R. typhina)

- prairie willow (Salix humilis)

Trees

- pignut hickory (Carya glabra)

- shagbark hickory (Carya ovata)

- white oak (Quercus alba)

- bur oak (Quercus macrocarpa)

- chinquapin oak (Quercus muehlenbergii)

- dwarf chinquapin oak (Quercus prinoides)

- red oak (Quercus rubra)

- black oak (Quercus velutina)

Noteworthy Animals

Oak openings and surrounding prairie habitat once supported a rich diversity of invertebrates including numerous butterflies, skippers, grasshoppers, and locusts. Mound-building ants and numerous grassland birds also thrived in savannas and prairies. The fragmented and degraded status of Midwestern oak savannas and prairies has resulted in the drastic decline of numerous insect and bird species associated with savanna habitats and prairie/savanna host plants. The now extinct passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) was likely a keystone species in oak ecosystems, roosting in oaks by the thousands.

Rare Plants

- Amorpha canescens (leadplant, state special concern)

- Asclepias purpurascens (purple milkweed, state special concern)

- Aster sericeus (western silvery aster, state threatened)

- Baptisia lactea (white false indigo, state special concern)

- Baptisia leucophaea (cream wild indigo, state endangered)

- Bouteloua curtipendula (side-oats grama grass, state threatened)

- Camassia scilloides (wild-hyacinth, state threatened)

- Corydalis flavula (yellow fumewort, state threatened)

- Dennstaedtia punctilobula (hay-scented fern, state threatened)

- Eryngium yuccifolium (rattlesnake-master, state threatened)

- Eupatorium sessilifolium (upland boneset, state threatened)

- Euphorbia commutata (tinted spurge, state threatened)

- Gentiana flavida (white gentian, state endangered)

- Gentiana puberulenta (downy gentian, state endangered)

- Geum triflorum (prairie-smoke, state threatened)

- Helianthus microcephalus (small wood sunflower, presumed extirpated from Michigan)

- Helianthus mollis (downy sunflower, state threatened)

- Hieracium paniculatum (panicled hawkweed, state special concern)

- Houstonia caerulea (bluets, state special concern)

- Kuhnia eupatorioides (false boneset, state special concern)

- Lactuca floridana (woodland lettuce, state threatened)

- Lechea minor (least pinweed, state special concern)

- Lechea stricta (erect pinweed, state special concern)

- Linum sulcatum (furrowed flax, state special concern)

- Onosmodium molle (marbleweed, presumed extirpated from Michigan)

- Oxalis violacea (violet wood-sorrel, state threatened)

- Panicum leibergii (Leiberg’s panic-grass, state threatened)

- Polytaenia nuttallii (prairie-parsley, presumed extirpated from Michigan)

- Ranunculus rhomboideus (prairie buttercup, state threatened)

- Rudbeckia subtomentosa (sweet coneflower, presumed extirpated from Michigan)

- Ruellia humilis (hairy ruellia, state threatened)

- Scutellaria elliptica (hairy skullcap, state special concern)

- Silene stellata (starry campion, state threatened)

- Sisyrinchium strictum (blue-eyed-grass, state special concern)

- Sporobolus clandestinus (dropseed, state special concern)

- Tomanthera auriculata (eared false foxglove, presumed extirpated from Michigan)

- Trichostema dichotomum (bastard pennyroyal, state threatened)

Rare Animals

- Accipiter cooperii (Cooper’s hawk, state special concern)

- Ammodramus henslowii (Henslow’s sparrow, state threatened)

- Ammodramus savannarum (grasshopper sparrow, state special concern)

- Atrytonopsis hianna (dusted skipper, state threatened)

- Catocala amestris (three-staff underwing, state endangered)

- Clonophis kirtlandii (Kirtland’s snake, state endangered)

- Cryptotis parva (least shrew, state threatened)

- Dendroica discolor (prairie warbler, state endangered)

- Elaphe o. obsoleta (black rat snake, state special concern)

- Erynnis p. persius (Persius duskywing, state threatened)

- Hesperia ottoe (ottoe skipper, state threatened)

- Incisalia henrici (Henry’s elfin, state special concern)

- Incisalia irus (frosted elfin, state threatened)

- Lanius ludovicianus migrans (migrant loggerhead shrike, state endangered)

- Lepyronia gibbosa (Great Plains spittlebug, state threatened)

- Lycaeides melissa samuelis (Karner blue butterfly, federal endangered and state threatened)

- Microtus ochrogaster (prairie vole, state endangered)

- Myotis sodalis (Indiana bat, federal/state endangered)

- Neoconocephalus ensiger (conehead grasshopper, state special concern)

- Nicrophorus americanus (American burying water beetle, state endangered)

- Oecanthus pini (pinetree cricket, state special concern)

- Orphulella p. pelidna (barrens locust, state special concern)

- Papaipema beeriana (Blazing star borer, state special concern)

- Papaipema sciata (Culver’s root borer, state special concern)

- Prosapia ignipectus (red-legged spittlebug, state special concern)

- Pygarctia spraguei (Sprague’s pygarctia, state special concern)

- Pyrgus centaureae wyandot (grizzled skipper, state special concern)

- Schinia indiana (phlox moth, state endangered)

- Schinia lucens (leadplant flower moth, state endangered)

- Scudderia fasciata (pine katydid, state special concern)

- Sistrurus c. catenatus (eastern massasauga, federal candidate species and state special concern)

- Spartiniphaga inops (spartina moth, state special concern)

- Speyeria idalia (regal fritillary, state endangered)

- Terrapene c. carolina (eastern box turtle, state special concern)

- Tympanuchus phasianellus (sharp-tailed grouse, state special concern)

- Tyto alba (barn owl, state endangered)

Biodiversity Management Considerations

The prime conservation priority for this globally imperiled community is to survey for restorable remnants. The existence of oak savanna depends on active restoration; this is especially true for oak openings. If remnants of oak openings are located, the first management step will be the restoration of the oak savanna physiognomy through prescribed fire and/or selective cutting or girdling. The process of restoring the open canopy conditions and eliminating the understory should be conducted gradually, undertaken over the course of several years taking care to minimize colonization by invasive plants, which can respond rapidly to increased levels of light and soil disturbance. Fire is the single most significant factor in preserving oak-savanna landscapes. In addition to maintaining open canopy conditions, prescribed fire promotes internal vegetative patchiness and high levels of grass and forb diversity, and deters the encroachment of woody vegetation and invasive plants. Numerous studies have indicated that fire intervals of one to three years bolster graminoid dominance, increase overall grass and forb diversity, and remove woody cover of saplings and shrubs.

Savannas were among some of the first locations chosen for settlement by early Europeans. Many towns, college campuses, parks, and cemeteries of the Midwest were established on former oak savanna. Early settlers of Michigan utilized oak openings for growing crops, pasturing livestock, and harvesting timber for fuel and building supplies. Alteration of historic fire regimes quickly shifted most oak savannas to closed-canopy oak forests. Oak savanna remnants are often depauperate in floristic diversity due to past disturbances and colonization by invasive species, many of which are shrubs that create dense shade and suppress or eliminate the graminoid species needed to carry fire.

Monitoring and control efforts to detect and remove invasive species are critical to the success of restoration projects. Invasive species that threaten the diversity and community structure of oak openings include spotted knapweed (Centaurea stoebe), common St. John’s-wort (Hypericum perforatum), black swallow-wort (Vincetoxicum nigrum), white swallow-wort (V. rossicum), Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis), Canada bluegrass (P. compressa), ox-eye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare), hawkweeds (Hieracium spp.), sheep sorrel (Rumex acetosella), bouncing bet (Saponaria officinalis), hoary alyssum (Berteroa incana), Oriental bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus), common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica), autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata), Eurasian honeysuckles (especially Lonicera morrowii, L. tatarica, and L. xbella), and multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora).

Variation

The character of oak savanna ecosystems can differ dramatically, primarily as the result of varying fire intensity and fire frequency, which are influenced by site factors such as climatic conditions, soil texture, topography, size of physiographic and vegetative units, and landscape context (e.g., proximity to water bodies). Infrequent, high-intensity fires kill mature oaks and produce savannas covered by abundant scrubby oak sprouts. Park-like openings with widely spaced trees and a graminoid- and forb-dominated ground layer are maintained by frequent, low-intensity fires that occur often enough to restrict maturation of oak grubs and encroachment by other woody species.

Similar Natural Communities

Bur oak plains, dry-mesic southern forest, lakeplain oak openings, mesic prairie, oak barrens, oak-pine barrens, and dry-mesic prairie.

Places to Visit

- No remaining sites occur on lands accessible to the public. However, readers may be able to find remnants of oak openings along railroad tracks and adjacent to cemeteries in southwestern Michigan.

Relevant Literature

- Anderson, R.C., and M.L. Bowles. 1999. Deep-soil savannas and barrens of the Midwestern United States. Pp. 155-170 in Savannas, barrens, and rock outcrop plant communities of North America, ed. R.C. Anderson, J.S. Fralish, and J.M. Baskin. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 480 pp.

- Cohen, J.G. 2004. Natural community abstract for oak openings. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 13 pp.

- Faber-Langendoen, D. 1993. A proposed classification for savannas in the Midwest. Background paper for the Midwest Oak Savanna Conference. 18 pp.

- Leach, M.K., and T.J. Givnish. 1999. Gradients in the composition, structure, and diversity of remnant oak savannas in southern Wisconsin. Ecological Monographs 69(3): 353-374.

- Minc, L.D., and D.A. Albert. 1990. Oak-dominated communities of southern Lower Michigan: Floristic and abiotic comparisons. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. Unpublished manuscript. 103 pp.

- Moseley, E.L. 1928. Flora of the oak openings. Ohio Academy of Science Special Paper 20: 79-134.

- Nuzzo, V. 1986. Extent and status of Midwest oak savanna: Presettlement and 1985. Natural Areas Journal 6(2): 6-36.

- Peterson, D.W., and P.B. Reich. 2001. Prescribed fire in oak savanna: Fire frequency effects on stand structure and dynamics. Ecological Applications 11(3): 914-927.

- Pruka, B., and D. Faber-Langendoen. 1995. Midwest oak ecosystem recovery plan: A call to action. Proceedings of the 1995 Midwest Oak Savanna and Woodland Ecosystem Conferences. Available http://www.epa.gov/glnpo/ecopage/upland/oak/oak95/app-b.htm. (Accessed: January 19, 2004.)

- Wing, L.W. 1937. Evidences of ancient oak openings in southern Michigan. Ecology 18: 170-171.

For a full list of references used to create this description, please refer to the natural community abstract for Oak Openings.

More Information

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: March 4, 2026).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.