Bur Oak Plains

Overview

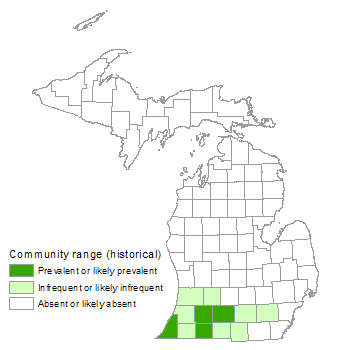

Bur oak plains was a fire-dependent, savanna community dominated by oaks, having between 10 and 30% canopy, with or without a shrub layer. The predominantly graminoid ground layer was comprised of species associated with both prairie and forest communities. Bur oak plains were found on mesic loams and typically occurred on level to slightly undulating sandy glacial outwash, and on river terraces. Bur oak plains have been extirpated from Michigan and are now known only from historical literature and data derived from severely disturbed sites.

Rank

Global Rank: G1SX

State Rank: SX - Presumed extirpated

Landscape Context

This natural community occurred on level to gently undulating or sloping glacial outwash plains, and also on river terraces, typically on the river’s western side, where fire frequency was highest. Bur oak plains occurred adjacent to more mesic communities, such as mesic prairie and wet-mesic prairie and also graded into the drier savanna and forest types such as oak openings and oak barrens, and dry-mesic southern forest and dry southern forest. Historically, bur oak plains occurred in a complex, shifting mosaic of fire-dependent upland and wetland communities.

Soils

Soils were fertile, fine-textured, loam, sandy loam or silt loam with neutral pH and good water-retaining capacity. Soils contained moderate to high amounts of organic matter and supported high abundance of graminoids and forbs.

Natural Processes

Repeated low-intensity fires working in concert with drought and windthrow maintained oak savanna ecosystems. Within mesic savanna systems, such as bur oak plains, it is likely that annual or semi-annual fires were the primary factor influencing savanna structure and composition. Fires prevented canopy closure and the dominance of woody vegetation. Bur oak plains were found primarily on level to gently rolling topography of outwash plains, a landscape in which fires occurred frequently and spread rapidly and evenly. The rich mesic soils of bur oak plains supported high coverage of grass and forb fuels. The frequent fire regime within these systems explains the canopy dominance of bur oak, which is the most fire resistant of the oaks with its deep roots, capacity to resprout, and thick, corky, insulating bark that prevents cambial damage by surface fires.

Oak savanna and prairie fires occur most often during the spring, late summer, and fall. Flammability peaks in the spring before grass and forb growth resumes and then again in the late summer and autumn after the above-ground biomass dies. Numerous biotic factors influence the patterning of vegetation of oak savannas. In addition to widely distributed overstory trees, savannas are characterized by scattered ant mounds. Mound-building ants play a crucial role in the soil development of prairies and savannas; ants mix and aerate the soil as they build tunnels and bring soil particles and nutrients to the topsoil from the subsoil. Herbivores can limit woody establishment and encroachment. Grasses and forbs help maintain the annual fire regime with their flammable properties. Open canopy conditions are also preserved by the development of a dense herbaceous litter that suspends tree propagules and interferes with the ability of radicles to reach the soil surface. Savanna trees influence vegetative composition by affecting the distribution of nutrients, light, and moisture.

Vegetation

Vegetation was described by Michigan settlers as park-like savanna of widely spaced mature oaks with virtually no shrub or subcanopy layer above the forb and graminoid layer. The broad-crowned, scattered oaks were typically of the same age cohort. The canopy layer generally varied from 10 to 30% cover and was dominated by bur oak (Quercus macrocarpa) and occasionally codominated by white oak (Q. alba). Canopy associates were limited to scattered hickories (Carya spp.) and black oak (Q. velutina). Oaks, especially black oak, were dispersed in the understory as fire-suppressed grubs that reached just over a meter tall. Shrubs occurred scattered or clumped in the understory. The most common shrubs were fire-tolerant species such as American hazelnut (Corylus americana), New Jersey tea (Ceanothus americanus), and leadplant (Amorpha canescens, state special concern). Shrubs such as gray dogwood (Cornus foemina), wild plum (Prunus americana), and smooth sumac (Rhus glabra) occasionally formed thickets in fire-protected microsites. Bur oak plains were characterized by a discontinuous layer of trees and shrubs and a continuous herbaceous layer. The flora of savannas were a mixture of prairie and forest species, with prairie forbs and grasses more abundant in high light areas and forest forbs and woody species in the areas of low light. Common grass species included big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), and Indian grass (Sorghastrum nutans). Prevalent forbs included hog peanut (Amphicarpaea bracteata), purple milkweed (Asclepias purpurascens, state threatened), false boneset (Brickellia eupatorioides, state special concern), prairie coreopsis (Coreopsis palmata, state threatened), showy tick-trefoil (Desmodium canadense), upland boneset (Eupatorium sessilifolium, state threatened), flowering spurge (Euphorbia corollata), northern bedstraw (Galium boreale), white gentian (Gentiana alba, state endangered), veiny pea (Lathyrus venosus), round-headed bush clover (Lespedeza capitata), wild-bergamot (Monarda fistulosa), Virginia mountain mint (Pycnanthemum virginianum), starry campion (Silene stellata, state threatened), yellow pimpernel (Taenidia integerrima), horse-gentian (Triosteum aurantiacum), feverwort (T. perfoliatum), and golden alexanders (Zizia aurea).

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Graminoids

- big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii)

- blue-joint (Calamagrostis canadensis)

- Bicknell’s sedge (Carex bicknellii)

- Leiberg’s panic grass (Dichanthelium leibergii)

- panic grass (Dichanthelium oligosanthes)

- porcupine grass (Hesperostipa spartea)

- switch grass (Panicum virgatum)

- little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium)

- Indian grass (Sorghastrum nutans)

- cordgrass (Spartina pectinata)

- prairie dropseed (Sporobolus heterolepis)

Forbs

- hog-peanut (Amphicarpaea bracteata)

- milkweeds (Asclepias purpurascens, A. syriaca, A. tuberosa, and A. verticillata)

- white false indigo (Baptisia lactea)

- false boneset (Brickellia eupatorioides)

- prairie coreopsis (Coreopsis palmata)

- tall coreopsis (Coreopsis tripteris)

- showy tick-trefoil (Desmodium canadense)

- prairie tick-trefoil (Desmodium illinoense)

- rattlesnake-master (Eryngium yuccifolium)

- flowering spurge (Euphorbia corollata)

- wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana)

- American columbo (Frasera caroliniensis)

- northern bedstraw (Galium boreale)

- wild geranium (Geranium maculatum)

- white gentian (Gentiana alba)

- woodland sunflower (Helianthus divaricatus)

- western sunflower (Helianthus occidentalis)

- pale-leaved sunflower (Helianthus strumosus)

- alum root (Heuchera americana)

- tall lettuce (Lactuca canadensis)

- veiny pea (Lathyrus venosus)

- round-headed bush-clover (Lespedeza capitata)

- hairy bush-clover (Lespedeza hirta)

- hoary puccoon (Lithospermum canescens)

- false spikenard (Maianthemum racemosum)

- wild-bergamot (Monarda fistulosa)

- prairie phlox (Phlox pilosa)

- common mountain mint (Pycnanthemum virginianum)

- early buttercup (Ranunculus fascicularis)

- yellow coneflower (Ratibida pinnata)

- black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta)

- starry campion (Silene stellata)

- rosin weed (Silphium integrifolium)

- prairie dock (Silphium terebinthinaceum)

- goldenrods (Solidago caesia, S. juncea, S. nemoralis, S. rigida, and S. speciosa)

- asters (Symphyotrichum laeve, S. oolentangiense, and S. pilosum)

- yellow pimpernel (Taenidia integerrima)

- purple meadow-rue (Thalictrum dasycarpum)

- common spiderwort (Tradescantia ohiensis)

- horse-gentian (Triosteum aurantiacum)

- feverwort (Triosteum perfoliatum)

- Culver’s root (Veronicastrum virginicum)

- American vetch (Vicia americana)

- pale vetch (Vicia caroliniana)

- golden alexanders (Zizia aurea)

- prairie violet (Viola pedatifida)

Woody Vines

- Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia)

- bristly greenbrier (Smilax hispida)

- poison-ivy (Toxicodendron radicans)

- summer grape (Vitis aestivalis)

- riverbank grape (Vitis riparia)

Shrubs

- leadplant (Amorpha canescens)

- New Jersey tea (Ceanothus americanus)

- gray dogwood (Cornus foemina)

- American hazelnut (Corylus americana)

- American plum (Prunus americana)

- sumacs (Rhus copallina, R. glabra, and R. typhina)

- pasture rose (Rosa carolina)

- prairie willow (Salix humilis)

Trees

- pignut hickory (Carya glabra)

- shagbark hickory (Carya ovata)

- white oak (Quercus alba)

- bur oak (Quercus macrocarpa)

- black oak (Quercus velutina)

Noteworthy Animals

Bur oak plains and surrounding prairie habitat once supported a rich diversity of invertebrates including numerous species of butterflies, skippers, grasshoppers, and locusts. Mound-building ants and numerous grassland birds also thrived in savannas and prairies. The fragmented and degraded status of Midwestern oak savannas and prairies has resulted in the drastic decline of numerous insect and bird species associated with savanna habitats and prairie/savanna host plants. The now extinct passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) was likely a keystone species in oak ecosystems, roosting in oaks by the thousands.

Rare Plants

- Amorpha canescens (leadplant, state special concern)

- Asclepias purpurascens (purple milkweed, state special concern)

- Aster sericeus (western silvery aster, state threatened)

- Baptisia leucophaea (cream wild indigo, state endangered)

- Bouteloua curtipendula (side-oats grama grass, state threatened)

- Camassia scilloides (wild-hyacinth, state threatened)

- Coreopsis palmata (prairie coreopsis, state threatened)

- Corydalis flavula (yellow fumewort, state threatened)

- Dodecatheon meadia (shooting-star, state endangered)

- Eryngium yuccifolium (rattlesnake-master, state threatened)

- Eupatorium sessilifolium (upland boneset, state threatened)

- Euphorbia commutata (tinted spurge, state threatened)

- Gentiana flavida (white gentian, state endangered)

- Gentiana puberulenta (downy gentian, state endangered)

- Geum triflorum (prairie-smoke, state threatened)

- Helianthus mollis (downy sunflower, state threatened)

- Hieracium paniculatum (panicled hawkweed, state special concern)

- Kuhnia eupatorioides (false boneset, special concern)

- Lechea minor (least pinweed, state special concern)

- Lechea stricta (erect pinweed, state special concern)

- Linum sulcatum (furrowed flax, state special concern)

- Oxalis violacea (violet wood-sorrel, state threatened)

- Rudbeckia subtomentosa (sweet coneflower, presumed extirpated from Michigan)

- Silene stellata (starry campion, state threatened)

- Sisyrinchium strictum (blue-eyed-grass, state special concern)

- Sporobolus clandestinus (dropseed, state special concern)

- Trichostema dichotomum (bastard pennyroyal, state threatened)

Rare Animals

- Accipiter cooperii (Cooper’s hawk, state special concern)

- Ammodramus henslowii (Henslow’s sparrow, state threatened)

- Ammodramus savannarum (grasshopper sparrow, state special concern)

- Atrytonopsis hianna (dusted skipper, state threatened)

- Catocala amestris (three-staff underwing, state endangered)

- Circus cyaneus (northern harrier, state special concern)

- Clonophis kirtlandii (Kirtland’s snake, state endangered)

- Cryptotis parva (least shrew, state threatened)

- Dendroica discolor (prairie warbler, state endangered)

- Elaphe o. obsoleta (black rat snake, state special concern)

- Erynnis p. persius (Persius duskywing, state threatened)

- Hesperia ottoe (ottoe skipper, state threatened)

- Incisalia henrici (Henry’s elfin, state special concern)

- Incisalia irus (frosted elfin, state threatened)

- Lanius ludovicianus migrans (migrant loggerhead shrike, state endangered)

- Lepyronia gibbosa (Great Plains spittlebug, state threatened)

- Lycaeides melissa samuelis (Karner blue butterfly, federal endangered and state threatened)

- Papaipema beeriana (Blazing star borer, state special concern)

- Microtus ochrogaster (prairie vole, state endangered)

- Myotis sodalis (Indiana bat, federal/state endangered)

- Neoconocephalus ensiger (conehead grasshopper, state special concern)

- Nicrophorus americanus (American burying water beetle, state endangered)

- Oecanthus pini (pinetree cricket, state special concern)

- Orphulella p. pelidna (barrens locust, state special concern)

- Papaipema sciata (Culver’s root borer, state special concern)

- Prosapia ignipectus (red-legged spittlebug, state special concern)

- Pygarctia spraguei (Sprague’s pygarctia, state special concern)

- Pyrgus centaureae wyandot (grizzled skipper, state special concern)

- Schinia indiana (phlox moth, state endangered)

- Schinia lucens (leadplant flower moth, state endangered)

- Scudderia fasciata (pine katydid, state special concern)

- Sistrurus c. catenatus (eastern massasauga, federal candidate species and state special concern)

- Spartiniphaga inops (spartina moth, state special concern)

- Speyeria idalia (regal fritillary, state endangered)

- Terrapene c. carolina (eastern box turtle, state special concern)

- Tympanuchus phasianellus (sharp-tailed grouse, state special concern)

- Tyto alba (barn owl, state endangered)

Biodiversity Management Considerations

The prime conservation priority for this globally imperiled community is to survey for restorable remnants. The future existence of all oak savannas in Michigan depends upon active restoration; this is especially true for bur oak plains. If bur oak plains remnants are located, the first management step will be the restoration of savanna physiognomy through prescribed fire and/or selective cutting or girdling. The process of restoring the open canopy conditions and eliminating the understory should be conducted gradually, undertaken over the course of several years. Fire is the single most significant restoration tool. In addition to maintaining open canopy conditions, prescribed fire promotes internal vegetative patchiness and high levels of grass and forb diversity, and deters the encroachment of woody vegetation and invasive non-natives. Numerous studies have indicated that fire intervals of one to three years bolster graminoid dominance, increase overall grass and forb diversity, and remove woody cover of saplings and shrubs.

Variation

Pure stands of bur oak of relatively similar-sized trees occurred in flat mesic areas with high fuel loads that likely supported annual fires. White oak codominated in slightly drier, less fertile sites with sloping topography, where herbaceous fuels were less dense and fire intensity less severe.

Similar Natural Communities

Lakeplain oak openings, mesic prairie, oak barrens, oak-pine barrens, oak openings, and wet-mesic prairie.

Places to Visit

- Extirpated.

Relevant Literature

- Brewer, L.G., T.W. Hodler, and H.A. Raup. 1984. Presettlement vegetation of southwestern Michigan. Michigan Botanist 23: 153-156.

- Brewer, R., and S. Kitler. 1989. Tree distribution in southwestern Michigan bur oak openings. Michigan Botanist 28: 73-79.

- Cohen, J.G. 2004. Natural community abstract for bur oak plains. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 13 pp.

- Chapman, K.A. 1984. An ecological investigation of native grassland in southern Lower Michigan. M.A. thesis, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, MI. 235 pp.

- Jones, J. 2000. Fire history of the bur oak savannas of Sheguiandah Township, Manitoulin Island, Ontario. Michigan Botanist 39: 3-15.

- Nuzzo, V. 1986. Extent and status of Midwest oak savanna: Presettlement and 1985. Natural Areas Journal 6(2): 6-36.

- Stout, A.B. 1946. The bur oak openings of southern Wisconsin. Transactions of the Wisconsin Academy of Science, Arts and Letters 36: 141-161.

For a full list of references used to create this description, please refer to the natural community abstract for Bur Oak Plains.

More Information

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: March 4, 2026).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.