Dry-mesic Northern Forest

Overview

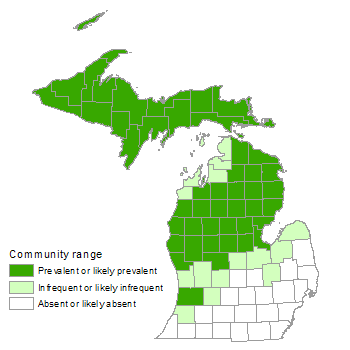

Dry-mesic northern forest is a pine or pine-hardwood forest type of generally dry-mesic sites located mostly north of the transition zone. The community historically originated in the wake of catastrophic fire and was maintained by frequent, low-intensity ground fires.

Rank

Global Rank: G4 - Apparently secure

State Rank: S3 - Vulnerable

Landscape Context

Dry mesic northern forest occurs principally on sandy glacial outwash, sandy glacial lakeplains, and less often on inland dune ridges, coarse-textured moraines, and thin glacial drift over bedrock.

Soils

Sand or loamy sand soils are extremely acid to very strongly acid and coarse- to medium-textured. A surface layer of mor humus is normally present due to the accumulation of pine needles.

Natural Processes

The natural disturbance regime of dry-mesic northern forest is characterized by both infrequent, catastrophic fire, with return intervals estimated to range from 120 to 300 years, and frequent, low-intensity surface fires, with return intervals estimated from 5 to 20 years. Additional important natural disturbance factors include windthrow and insect epidemics.

Vegetation

White pine (Pinus strobus) is nearly always a dominant or important canopy species within this forest type, often forming a supercanopy above other tree species. Red pine (Pinus resinosa) and hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) are frequently present and occasionally codominant with white pine in the canopy or supercanopy. Hardwood associates include white oak (Quercus alba), black oak (Q. velutina), red oak (Q. rubra), and red maple (Acer rubrum). Paper birch (Betula papyrifera), aspen (Populus tremuloides and P. grandidentata), and balsam poplar (P. balsamifera) are also common in the overstory. Balsam fir (Abies balsamea) and white spruce (Picea glauca) are often present in the subcanopy, especially in fire-suppressed systems. Bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum) often dominates the ground layer. Characteristic species of the shrub layer include serviceberries (Amelanchier spp.), beaked hazelnut (Corylus cornuta), bush honeysuckle (Diervilla lonicera), huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata), witch hazel (Hamamelis virginiana), American fly honeysuckle (Lonicera canadensis), choke cherry (Prunus virginiana), and blueberries (Vaccinium spp.). Typical ground layer species include wild sarsaparilla (Aralia nudicaulis), pipsissewa (Chimaphila umbellata), goldthread (Coptis trifolia), bunchberry (Cornus canadensis), trailing arbutus (Epigaea repens), wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens), twin flower (Linnaea borealis), partridge berry (Mitchella repens), gay wings (Polygala paucifolia), and starflower (Trientalis borealis). The presence of chlorophyll-free, parasitic and saprophytic seed plants such as Indian pipes (Monotropa uniflora), pinesap (Hypopitys monotropa), coral root orchids (Corallorhiza spp.), and pine-drops (Pterospora andromedea, state threatened) is a common feature of dry-mesic northern forest.

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Graminoids

- wavy hair grass (Avenella flexuosa)

- long-awned wood grass (Brachyelytrum aristosum)

- Pennsylvania sedge (Carex pensylvanica)

- poverty oats (Danthonia spicata)

- rice grass (Oryzopsis asperifolia)

Forbs

- wild columbine (Aquilegia canadensis)

- wild sarsaparilla (Aralia nudicaulis)

- poke milkweed (Asclepias exaltata)

- blue-bead lily (Clintonia borealis)

- goldthread (Coptis trifolia)

- coral-root orchids (Corallorhiza maculata and C. trifida)

- pink lady-slipper (Cypripedium acaule)

- large-leaved aster (Eurybia macrophylla)

- rattlesnake plantains (Goodyera oblongifolia and G. pubescens)

- pinesap (Hypopitys monotropa)

- twinflower (Linnaea borealis)

- Canada mayflower (Maianthemum canadense)

- partridge berry (Mitchella repens)

- Indian-pipe (Monotropa uniflora)

- gay-wings (Polygala paucifolia)

- pine-drops (Pterospora andromedea)

- large-leaved shinleaf (Pyrola elliptica)

- starflower (Trientalis borealis)

Ferns

- wood ferns (Dryopteris spp.)

- bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum)

Fern Allies

- ground-pine (Dendrolycopodium obscurum)

Shrubs

- serviceberries (Amelanchier spp.)

- pipsissewa (Chimaphila umbellata)

- bunchberry (Cornus canadensis)

- beaked hazelnut (Corylus cornuta)

- bush honeysuckle (Diervilla lonicera)

- trailing arbutus (Epigaea repens)

- wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens)

- huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata)

- witch-hazel (Hamamelis virginiana)

- Canadian fly honeysuckle (Lonicera canadensis)

- choke cherry (Prunus virginiana)

- blueberries (Vaccinium angustifolium and V. myrtilloides)

Trees

- balsam fir (Abies balsamea)

- striped maple (Acer pensylvanicum)

- red maple (Acer rubrum)

- serviceberries (Amelanchier arborea and A. laevis)

- paper birch (Betula papyrifera)

- white spruce (Picea glauca)

- black spruce (Picea mariana)

- red pine (Pinus resinosa)

- white pine (Pinus strobus)

- big-toothed aspen (Populus grandidentata)

- quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides)

- white oak (Quercus alba)

- red oak (Quercus rubra)

- black oak (Quercus velutina)

- hemlock (Tsuga canadensis)

Noteworthy Animals

This community provides summer nesting habitat for many neotropical migrants, especially interior forest obligates such as black-throated blue warbler (Dendroica caerulescens), black-throated green warbler (Dendroica virens), scarlet tanager (Piranga olivacea), and ovenbird (Seiurus aurocapillus). Where the community occurred in close proximity to streams and lakes, beaver likely played a role in reducing mesophytic invasion of the subcanopy and understory, selectively removing shade-tolerant species.

Rare Plants

- Arnica cordifolia (heart-leaved arnica, state endangered)

- Clematis occidentalis (purple clematis, state threatened)

- Dalibarda repens (false violet, state threatened)

- Danthonia compressa (flattened oat grass, state special concern)

- Erigeron acris (fleabane, state special concern)

- Oplopanax horridus (devil’s-club, state threatened)

- Osmorhiza depauperata (sweet cicely, state threatened)

- Pterospora andromeda (pine-drops, state threatened)

- Senecio indecorus (rayless mountain ragwort, state threatened)

Rare Animals

- Accipiter gentilis (northern goshawk, state special concern)

- Falco columbarius (merlin, state threatened)

- Haliaeetus leucocephalus (bald eagle, state threatened)

- Pandion haliaetus (osprey, state threatened)

- Picoides arcticus (black-backed woodpecker, state special concern)

Biodiversity Management Considerations

Fire suppression can result in the failure of pines to regenerate, invasion and maturation of shade-tolerant tree species, and eventual conversion to mesic forest. Prescribed fire management can be used to promote pine establishment and regeneration. Where fire is not feasible, effects of surface fire can be mimicked by thinning, mechanically scarifying the soils, and girdling and herbiciding competing vegetation. Under-planting pine seedlings can be used to reestablish pines where a natural seed source is unavailable.

Monitoring and control efforts to detect and remove invasive species are critical to the long-term viability of dry-mesic northern forest. By outcompeting native species, invasives alter vegetation structure, reduce species diversity, and disrupt ecological processes. Invasive plants that may have potential to threaten diversity and alter community structure in dry-mesic northern forest include garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata), spotted knapweed (Centaurea stoebe), common St. John’s-wort (Hypericum perforatum), hawkweeds (Hieracium spp.), sheep sorrel (Rumex acetosella), Canada bluegrass (Poa compressa), Kentucky bluegrass (P. pratensis), autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata), common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica), Eurasian honeysuckles (especially Lonicera morrowii, L. tatarica, and L. xbella), and multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora).

Variation

Species composition and community structure of dry-mesic northern forest vary regionally and are strongly influenced by historic fire regimes, climatic conditions, landform, soil texture, topography, and landscape context (i.e., proximity to water bodies and fire-resistant or fire-conducing plant communities). White oak-white pine forests are prevalent on areas of sandy outwash plain and lakeplain in far western, central Lower Michigan, both north and south of the climatic tension zone, on areas of sandy outwash plain and lakeplain. White pine-red pine forest occurs in the northern Lower and Upper Peninsulas on outwash plains, rolling moraines, and inland dune ridges. Sandy, coarse-textured morainal slopes and ridges in northern Lower Michigan support forests of white pine, red pine, and oaks. Moderately drained sand lakeplains and outwash from Saginaw Bay through the Upper Peninsula historically supported white pine forest and hemlock-white pine forest. Thin glacial drift over bedrock in the western Upper Peninsula supports forests dominated by white pine, red pine, and red oak. Dry-mesic northern forests found on inland dune systems tend to be narrow and linear, like the dunes they occupy. Forests surrounding lakes and alongside rivers and streams are also linear. Historically, the most extensive dry-mesic northern forests occurred on broad areas of outwash and lakeplain.

Similar Natural Communities

Dry northern forest, hardwood-conifer swamp, mesic northern forest, northern bald, granite bedrock glade, volcanic bedrock glade, oak-pine barrens, and wooded dune and swale complex.

Places to Visit

- Estivant Pines Nature Sanctuary, Michigan Nature Association, Keweenaw Co.

- Hartwick Pines, Hartwick Pines State Park, Crawford Co.

- Nebo Trail, Wilderness State Park, Emmet Co.

- Swamp Lakes, Newberry State Forest Management Unit and The Nature Conservancy (Swamp Lakes Preserve), Luce Co.

- Turner Creek Forest, Barry State Game Area, Barry Co.

- Two-Hearted Lakes, The Nature Conservancy (Two-Hearted River Forest Preserve), Luce Co.

Relevant Literature

- Brubaker, L.B. 1975. Postglacial forest patterns associated with till and outwash in northcentral Upper Michigan. Quaternary Research 5: 499-527.

- Cohen, J.G. 2002. Natural community abstract for dry-mesic northern forest. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 12 pp.

- Heinselman, M.L. 1973. Fire in the virgin forests of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area, Minnesota. Journal of Quaternary Research 3: 329-382.

- McRae, D.J., T.J. Lynham, and R.J. Frech. 1994. Understory prescribed burning in red pine and white pine. Forestry Chronicle 70(4): 395-401.

- Quinby, P.A. 1991. Self-replacement in old-growth white pine forests of Temagami, Ontario. Forest Ecology and Management 41: 95-109.

- Stearns, F. 1950. The composition of a remnant of white pine forest in the Lake States. Ecology 31(2): 290-292.

- Van Wagner, C.E. 1970. Fire and red pine. Proceedings of the Annual Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference 10: 211-219.

- Whitney, G.C. 1986. Relation of Michigan’s presettlement pine forest to substrate and disturbance history. Ecology 67(6): 1548-1559.

For a full list of references used to create this description, please refer to the natural community abstract for Dry-mesic Northern Forest.

More Information

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: December 16, 2025).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.