Mesic Northern Forest

Overview

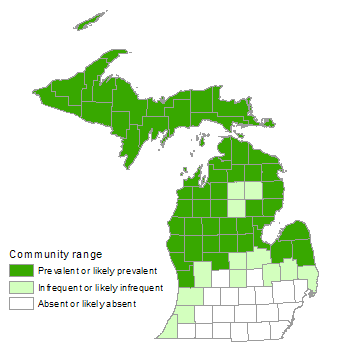

Mesic northern forest is a forest type of moist to dry-mesic sites lying mostly north of the climatic tension zone, characterized by the dominance of northern hardwoods, particularly sugar maple (Acer saccharum) and American beech (Fagus grandifolia). Conifers such as hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) and white pine (Pinus strobus) are frequently important canopy associates. This community type breaks into two broad classes: northern hardwood forest and hemlock-hardwood forest. It is primarily found on coarse-textured ground and end moraines, and soils are typically loamy sand to sandy loam. The natural disturbance regime is characterized by gap-phase dynamics; frequent, small windthrow gaps allow for the regeneration of the shade-tolerant canopy species. Catastrophic windthrow occurred infrequently with several generations of trees passing between large-scale, severe disturbance events. Historically, mesic northern forest occurred as a matrix system, dominating vast areas of mesic uplands in the Great Lakes region. These forests were multi-generational, with old-growth conditions lasting many centuries.

Rank

Global Rank: G4 - Apparently secure

State Rank: S3 - Vulnerable

Landscape Context

Mesic northern forests are found chiefly on coarse-textured ground and end moraines, but are also common on silty/clayey lakeplains, thin glacial till over bedrock, and medium-textured moraines. The community occurs locally on kettle-kame topography, moderately well-drained to well-drained sandy lakeplain, and on north-facing sand dunes as far south as Berrien County in southern Lower Michigan.

Soils

A wide variety of soils support mesic northern forest but most typically it occurs on loamy sand to sandy loam and occasionally on sand, loam, and clay. Soils range widely in pH from extremely acidic to moderately alkaline but are more commonly extremely acid to medium acid.

Natural Processes

The natural disturbance regime is characterized by frequent, small-scale wind disturbance or gap-phase dynamics and infrequent intermediate- and large-scale wind events. Severe low pressure systems are a significant source of small-scale canopy gaps. Catastrophic windthrow, from tornadoes and downbursts, occurs infrequently (estimated return intervals are >1000 years). Catastrophic fire was historically correlated with catastrophic windthrow, especially in hemlock-dominated forests. Due to the long interval between large-scale disturbance events, mesic northern forests tend to be multi-generational, with old-growth conditions lasting several centuries. Ice storms affecting hundreds to thousands of acres act to thin canopy cover and promote tree regeneration. Historically, where mesic northern forest bordered fire-dependent pine and oak-pine systems, low-intensity surface fires may have infrequently burned portions of the ground layer, exposing patches of mineral soil and thereby promoting regeneration of small-seeded conifers.

Vegetation

Dominant tree species of mesic northern forest include sugar maple, American beech, and hemlock. While sugar maple most frequently dominates the community throughout Michigan, American beech is excluded from the western Upper Peninsula by extremely low winter temperatures. Other important components of the canopy include yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis), white ash (Fraxinus americana), basswood (Tilia americana), red oak (Quercus rubra), northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis), and white pine, which can attain supercanopy status. In sugar maple stands, basswood or American beech are often important, along with yellow birch, white ash, and red oak. The proportion of conifers and hardwoods other than sugar maple often increases when groundwater or bedrock influences the rooting zone. In stands where hemlock predominates or is accompanied by sugar maple, canopy associates may include: yellow birch, red maple (Acer rubrum), American beech, paper birch (Betula papyrifera), red oak, and white pine. Forests dominated by sugar maple and northern white-cedar are found in dunes or over calcareous bedrock.

Typical subcanopy species include balsam fir (Abies balsamea), ironwood (Ostrya virginiana), and American elm (Ulmus americana). American elm was a canopy dominant before the introduction of Dutch elm disease. The shrub layer is characterized by striped maple (Acer pensylvanicum), mountain maple (A. spicatum), alternate-leaved dogwood (Cornus alternifolia), beaked hazelnut (Corylus cornuta), leatherwood (Dirca palustris), American fly honeysuckle (Lonicera canadensis), prickly gooseberry (Ribes cynosbati), red elderberry (Sambucus racemosa), and maple-leaved arrow-wood (Viburnum acerifolium). Prevalent species in the ground layer, representing a broad range of moisture conditions, include doll’s eyes (Actaea pachypoda), red baneberry (A. rubra), maidenhair fern (Adiantum pedatum), wild leek (Allium tricoccum), wild sarsaparilla (Aralia nudicaulis), jack-in-the-pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum), rattlesnake fern (Botrypus virginianus), pubescent sedge (Carex hirtifolia), plantain-leaf sedge (C. plantaginea), blue cohosh (Caulophyllum thalictroides), bunchberry (Cornus canadensis), spinulose woodfern (Dryopteris carthusiana), fragrant bedstraw (Galium triflorum), hairy sweet cicely (Osmorhiza claytonii), downy Solomon seal (Polygonatum pubescens), false Solomon’s seal (Maianthemum racemosum), rose twisted stalk (Streptopus lanceolatus), large-flowered bellwort (Uvularia grandiflora), and trilliums (Trillium spp.).

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Graminoids

- long-awned wood grass (Brachyelytrum aristosum)

- sedges (Carex albursina, C. arctata, C. deweyana, C. hirtifolia, C. intumescens, C. leptonervia, C. pedunculata, C. plantaginea, C. radiata, C. rosea, C. woodii, and others)

- bottlebrush grass (Elymus hystrix)

- western fescue (Festuca occidentalis)

- wood millet (Milium effusum)

- rough-leaved rice-grass (Oryzopsis asperifolia)

- bluegrasses (Poa alsodes and P. saltuensis)

- false melic (Schizachne purpurascens)

Forbs

- baneberries (Actaea pachypoda and A. rubra)

- wild leek (Allium tricoccum)

- wild sarsaparilla (Aralia nudicaulis)

- jack-in-the-pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum)

- blue cohoshes (Caulophyllum giganteum and C. thalictroides)

- enchanter’s-nightshade (Circaea canadensis)

- Carolina spring-beauty (Claytonia caroliniana)

- blue-bead lily (Clintonia borealis)

- goldthread (Coptis trifolia)

- coral-root orchids (Corallorhiza spp.)

- squirrel-corn (Dicentra canadensis)

- Dutchman’s breeches (Dicentra cucullaria)

- beech drops (Epifagus virginiana)

- yellow trout lily (Erythronium americanum)

- bedstraw (Galium triflorum)

- Canada mayflower (Maianthemum canadense)

- false spikenard (Maianthemum racemosum)

- Indian cucumber-root (Medeola virginiana)

- partridge berry (Mitchella repens)

- Indian pipes (Monotropa uniflora)

- hairy sweet cicely (Osmorhiza claytonii)

- northern wood-sorrel (Oxalis acetosella)

- downy Solomon seal (Polygonatum pubescens)

- twisted-stalks (Streptopus spp.)

- starflower (Trientalis borealis)

- common trillium (Trillium grandiflorum)

- large-flowered bellwort (Uvularia grandiflora)

- sweet white violet (Viola blanda)

- Canada violet (Viola canadensis)

- yellow violet (Viola pubescens)

- great-spurred violet (Viola selkirkii)

- common blue violet (Viola sororia)

Ferns

- maidenhair fern (Adiantum pedatum)

- lady fern (Athyrium filix-femina)

- rattlesnake fern (Botrypus virginianus)

- spinulose woodfern (Dryopteris carthusiana)

- glandular woodfern (Dryopteris intermedia)

- marginal woodfern (Dryopteris marginalis)

- oak fern (Gymnocarpium dryopteris)

- ostrich fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris)

- sensitive fern (Onoclea sensibilis)

- northern beech-fern (Phegopteris connectilis)

Fern Allies

- ground-pines (Dendrolycopodium dendroideum and D. obscurum)

- shining clubmoss (Huperzia lucidula)

- running ground-pine (Lycopodium clavatum)

- stiff clubmoss (Spinulum annotinum)

Shrubs

- bunchberry (Cornus canadensis)

- beaked hazelnut (Corylus cornuta)

- leatherwood (Dirca palustris)

- Canadian fly honeysuckle (Lonicera canadensis)

- prickly gooseberry (Ribes cynosbati)

- red elderberry (Sambucus racemosa)

- maple-leaved arrow-wood (Viburnum acerifolium)

Trees

- balsam fir (Abies balsamea)

- striped maple (Acer pensylvanicum)

- red maple (Acer rubrum)

- sugar maple (Acer saccharum)

- mountain maple (Acer spicatum)

- yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis)

- paper birch (Betula papyrifera)

- alternate-leaved dogwood (Cornus alternifolia)

- American beech (Fagus grandifolia)

- white ash (Fraxinus americana)

- ironwood (Ostrya virginiana)

- white pine (Pinus strobus)

- red oak (Quercus rubra)

- northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis)

- basswood (Tilia americana)

- hemlock (Tsuga canadensis)

Noteworthy Animals

Large contiguous tracts of old-growth and mature mesic northern forest provide important habitat for cavity nesters, species of detritus-based food webs, canopy-dwelling species, and interior forest obligates, including numerous neotropical migrants, such as black-throated blue warbler (Dendroica caerulescens), black-throated green warbler (Dendroica virens), scarlet tanager (Piranga olivacea), and ovenbird (Seiurus aurocapillus).

Rare Plants

- Asplenium rhizophyllum (walking fern, state threatened)

- Asplenium scolopendrium var. americanum (Hart’s-tongue fern, federal threatened and state endangered)

- Asplenium trichomanes-ramosum (green spleenwort, state threatened)

- Botrychium mormo (goblin moonwort, state threatened)

- Carex assiniboinensis (Assiniboia sedge, state threatened)

- Carex novae-angliae (New England sedge, state threatened)

- Cystopteris laurentiana (Laurentian fragile fern, state special concern)

- Dentaria maxima (large toothwort, state threatened)

- Disporum hookeri (fairy bells, state endangered)

- Dryopteris filix-mas (male fern, state special concern)

- Galearis spectabilis (showy orchis, state threatened)

- Galium kamtschaticum (bedstraw, state threatened)

- Gnaphalium sylvaticum (cudweed, state threatened)

- Panax quinquefolius (ginseng, state threatened)

- Tipularia discolor (cranefly orchid, state threatened)

- Triphora trianthophora (three-birds orchid, state threatened)

- Viola novae-angliae (New England violet, state threatened)

Rare Animals

- Accipiter cooperii (Cooper’s hawk, state special concern)

- Accipiter gentilis (northern goshawk, state special concern)

- Alces alces (moose, state special concern)

- Buteo lineatus (red-shouldered hawk, state threatened)

- Canis lupus (gray wolf, state threatened)

- Microtus pinetorum (woodland vole, state special concern)

Biodiversity Management Considerations

Biodiversity management requires a multi-scale approach and can be realized by taking the following actions. Emulate natural disturbance regimes and manage landscapes within the historical range of variability. Leave large tracts (especially old-growth and late-successional forest) unharvested and allow natural processes to operate unhindered. Increase the acreage of mature mesic northern forest by allowing early-successional forest to convert to late-successional forest. Reduce forest fragmentation by decreasing forest harvest levels, halting the creation of wildlife openings in forested landscapes, closing redundant forest roads, limiting the creation of new roads, and allowing wildlife openings and old field to revert to forest. Extend rotation periods of managed forests beyond 100 years to allow for the development of late-successional characteristics and species. Reduce high deer densities to levels at which herbivory no longer limits tree recruitment and reduces floral diversity. Maximize forest continuity by retaining large-diameter snags, coarse woody debris, and old, living trees. Where large-diameter snags and coarse woody debris are lacking, increase structural heterogeneity by creating snags through girdling, felling trees, and if necessary, skidding in large-diameter, long-lived, slowly decaying conifer species. Retain and promote hemlock, white pine, and northern white-cedar where they persist. Maintain and create suitable sites for conifer establishment by retention of large-diameter nurse logs and, in fire-prone landscapes, exposure of mineral soil through infrequent, low-intensity prescribed surface fires. Erect deer exclosures to protect hemlock, white pine, and cedar regeneration. Where hemlock and white pine seed sources are absent, underplant saplings. Mimic gap-phase dynamics and promote dead-tree dynamics when harvesting. Maintain genetic legacy of managed forests by retaining old trees and promoting natural regeneration.

Monitoring and control efforts to detect and remove invasive species before they become widespread are critically important for long-term viability of mesic northern forest. By outcompeting native species, invasive plants alter vegetation structure, reduce species diversity, and disrupt ecological processes. Invasive plant species that threaten the diversity and community structure in mesic northern forest include garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata), Dame’s rocket (Hesperis matronalis), Eurasian honeysuckles (especially Lonicera morrowii, L. tatarica, and L. xbella), Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii), common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica), glossy buckthorn (Frangula alnus), multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora), and Norway maple (Acer platanoides).

Intensive and pervasive anthropogenic disturbance during the past 150 years has altered the extent, landscape pattern, natural processes, structure, and species composition of mesic northern forest. Mesic northern forest, especially old-growth and late-successional forest, has been drastically reduced in acreage. This matrix community has become fragmented, with most old-growth and late-successional stands now persisting as remnant patches enmeshed in a matrix of agricultural lands, early-successional forest, and young northern hardwoods. Short-rotation timber management has replaced gap-phase dynamics as the dominant disturbance factor affecting structure and species composition. Structural alterations include the reduction of large-diameter trees, snags, and coarse woody debris. Hemlock and white pine have declined in importance within these systems. Fire suppression in nearby fire-prone systems has probably contributed to the lack of conifer recruitment in some sites as has a lack of suitable substrates for seedling establishment such as large-diameter nurse logs. Chronically high deer densities have further limited tree recruitment and altered floral composition and structure.

Variation

Mesic northern forest is a broadly defined community type with numerous regional, physiographic, and edaphic variations. Two broad classes are recognized, hardwood-dominated forest and hemlock-hardwood forest.

In the northern Lower Peninsula and in the eastern Upper Peninsula, sugar maple and beech commonly occur as codominants, frequently thriving on heavy-textured soils such as silt loam and clay loam. Beech is absent from most systems in the western Upper Peninsula, likely due to the extreme minimum winter temperatures, shorter growing season, and increased dryness. Basswood, characteristic of nutrient-rich sites, is most prevalent in mixed-hardwood stands in the western Upper Peninsula and most closely associated with sugar maple.

Hemlock-hardwood forests may include a variety of conifers and northern hardwoods, which vary in relative dominance depending on climate, landform, soils, aspect, drainage, and proximity to inland lakes or the Great Lakes. Some of dominant canopy trees in these mixed forests include hemlock, white pine, northern white-cedar, yellow birch, American beech, and sugar maple. Hemlock, white pine, northern white-cedar, and yellow birch increase in importance in areas with modified climate (areas near the Great Lakes) or microclimate (adjacent to inland lakes and rivers, in ravines, and slopes with north-to-east aspects) or poor drainage (poorly drained lakeplains). Extensive tracts of sugar maple and northern white-cedar were located in dunes or over calcareous bedrock and today are found locally in dunes along the Great Lakes shoreline, on Great Lakes islands, and on the drumlin fields of Menominee County. White pine mixed with northern hardwoods reached its greatest abundance on drier southeast-facing slopes of well-drained moraines and ice-contact features.

Similar Natural Communities

Mesic southern forest, dry-mesic northern forest, and hardwood-conifer swamp.

Places to Visit

- Betsy Lake, Tahquamenon Falls State Park, Luce Co. and Chippewa Co.

- Lake Gogebic, Lake Gogebic State Park, Gogebic Co.

- McCormick Tract, McCormick Research Natural Area, Ottawa National Forest, Marquette Co.

- Murphy Lake Hemlocks, Murphy Lake State Game Area, Oakland Co.

- P. J. Hoffmaster State Park, Ottawa Co. and Muskegon Co.

- Pictured Rocks, Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore, Alger Co.

- Porcupine Mountains, Porcupine Mountains Wilderness State Park, Gogebic Co. and Ontonagon Co.

- Port Huron Mesic Northern Forest, Port Huron State Game Area, St. Clair Co.

- Sleeping Bear Dunes, Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, Leelanau Co.

- Sylvania, Sylvania Wilderness and Recreation Area, Ottawa National Forest, Gogebic Co.

- Walloon Lake, Gaylord State Forest Management Unit, Charlevoix Co.

Relevant Literature

- Augustine, D.J., and L.E. Frelich. 1998. Effects of white-tailed deer on populations of an understory forb in fragmented deciduous forests. Conservation Biology 12(5): 995-1004.

- Cohen, J.G. 2000. Natural community abstract for mesic northern forest. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 7 pp.

- Crow, T.R., and A.H. Perera. 2004. Emulating natural landscape disturbance in forest management — An introduction. Landscape Ecology 19: 231-233.

- Frelich, L.E. 1995. Old forest in the Lake States today and before European settlement. Natural Areas Journal 15: 157-167.

- Frelich, L.E., and C.G. Lorimer. 1991. Natural disturbance regimes in hemlock-hardwood forests of the Upper Great Lakes region. Ecological Monographs 61(2): 145-164.

- Leahy, M.J., and K.S. Pregitzer. 2003. A comparison of presettlement and present-day forests in northeastern Lower Michigan. American Midland Naturalist 149(1): 71-89.

- Lorimer, C.G., and L. E. Frelich. 1994. Natural disturbance regimes in old growth northern hardwoods. Journal of Forestry 92: 33-38.

- Mladenoff, D.J., and F. Stearns. 1993. Eastern hemlock regeneration and deer browsing in the northern Great Lakes region: A re-examination and model simulation. Conservation Biology 7(4): 889-900.

- Mladenoff, D.J., M.A. White, J. Pastor, and T.R. Crow. 1993. Comparing spatial pattern in unaltered old-growth and disturbed forest landscapes. Ecological Applications 3(2): 294-306.

- Rooney, T.P., and D.M. Waller. 1998. Local and regional variation in hemlock seedling establishment in forests of the upper Great Lakes region, USA. Forest Ecology and Management 111: 211-224.

- Schulte, L.A., and D.J. Mladenoff. 2005. Severe wind and fire regimes in northern forests: Historical variability at the regional scale. Ecology 86(2): 431-445.

- Tyrrell, L.E., and T.R. Crow. 1994. Dynamics of dead wood in old-growth hemlock-hardwood forests of northern Wisconsin and northern Michigan. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 24: 1672-1683.

- Whitney, G.C. 1987. An ecological history of the Great Lakes forest of Michigan. Journal of Ecology 75(3): 667-684.

- Woods, K.D. 2004. Intermediate disturbance in a late-successional hemlock-northern hardwood forest. Journal of Ecology 92: 464-476.

- Zhang, Q., K.S. Pregitzer, and D.D. Reed. 2000. Historical changes in the forests of the Luce District of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. American Midland Naturalist 143(1): 94-110.

For a full list of references used to create this description, please refer to the natural community abstract for Mesic Northern Forest.

More Information

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: September 10, 2025).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.