Northern Wet Meadow

Overview

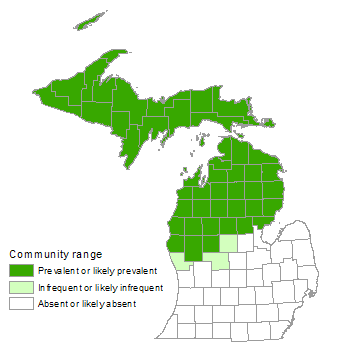

Northern wet meadow is an open, groundwater-influenced, sedge- and grass-dominated wetland that occurs in the northern Lower and Upper Peninsulas and typically borders streams but is also found on pond and lake margins and above beaver dams. Soils are nearly always sapric peat and range from strongly acid to neutral in pH. Open conditions are maintained by seasonal flooding, beaver-induced flooding, and fire.

Rank

Global Rank: G4G5 - Rank is uncertain, ranging from apparently secure to secure

State Rank: S4 - Apparently secure

Landscape Context

Northern wet meadow occurs on glacial lakebeds, in channels of glacial outwash, and in depressions on glacial outwash and moraines. The community frequently occurs along the margins of lakes, ponds, and streams where seasonal flooding or beaver-induced flooding is common. Northern wet meadow is regularly found adjacent to other wetland communities, often in large wetland complexes. Along streams, northern wet meadow typically borders northern shrub thicket and swamp forest. On the edges of inland lakes, northern wet meadow often borders emergent marsh and less frequently northern fen. It may also occur along the Great Lakes shoreline within extensive areas of Great Lakes marsh.

Soils

Northern wet meadow typically occurs on organic soils such as well-decomposed sapric peat, but saturated mineral soil may also support the community. Soil pH typically ranges from strongly acid to neutral. Northern wet meadow occurs on more acidic soils compared to southern wet meadow, which is found on neutral to strongly alkaline soils.

Natural Processes

Northern wet meadows are strongly influenced by groundwater with water levels fluctuating seasonally, reaching their peaks in spring and lows in late summer. Water levels typically remain at or near the soil surface throughout the year. Beaver-induced flooding may also play an important role in maintaining the community by occasionally raising water levels and killing encroaching trees and shrubs. Beaver can also help create new northern wet meadows by flooding swamp forests and northern shrub thickets and thus creating suitable habitat for the growth of shade-intolerant wet meadow species. Fire is also an important natural disturbance within these systems. By reducing leaf litter and allowing light to reach the soil surface and stimulate seed germination, fire can play an important role in maintaining wet meadow seed banks and species diversity. Fire helps prevent declines in species richness in many community types by temporarily reducing competition from robust perennials and creating micro-niches for small species. In the absence of fire, a thick layer of leaf litter can develop that stifles seed germination and seedling establishment. Another critically important attribute of fire for maintaining open sedge meadow is its ability to temporarily reduce shrub cover. In the absence of fire or flooding, all but the wettest sedge meadows typically convert to shrub thicket and eventually swamp forest.

Vegetation

Northern wet meadow is a sedge-dominated wetland that typically has 100% vegetative cover in the ground layer and is often dominated by tussock sedge (Carex stricta). Other characteristic sedges include lake sedge (C. lacustris), wiregrass sedge (C. lasiocarpa), beaked sedge (C. utriculata), and blister sedge (C. vesicaria). The most dominant grass species is bluejoint grass (Calamagrostis canadensis). Other common grasses include fringed brome (Bromus ciliatus), rattlesnake grass (Glyceria canadensis), fowl manna grass (G. striata), marsh wild timothy (Muhlenbergia glomerata), leafy satin grass (M. mexicana), and fowl meadow grass (Poa palustris). Bald spike-rush (Eleocharis erythropoda), broad-leaved cat-tail (Typha latifolia), twig-rush (Cladium mariscoides), and green bulrush (Scirpus atrovirens) are also common graminoids. A wide variety of wetland forbs occur in northern wet meadow. The following are some of the more common species: Canada anemone (Anemone canadensis), swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata), marsh bellflower (Campanula aparinoides), water-hemlocks (Cicuta bulbifera and C. maculata), swamp thistle (Cirsium muticum), marsh cinquefoil (Comarum palustre), flat-topped white aster (Doellingeria umbellata), downy willow-herb (Epilobium strictum), joe-pye-weed (Eutrochium maculatum), common boneset (Eupatorium perfoliatum), grass-leaved goldenrod (Euthamia graminifolia), rough bedstraw (Galium asprellum), small bedstraw (G. trifidum), jewelweed (Impatiens capensis), wild blue flag (Iris versicolor), marsh pea (Lathyrus palustris), American water-horehound (Lycopus americanus), northern bugleweed (L. uniflorus), tufted loosestrife (Lysimachia thyrsiflora), wild mint (Mentha canadensis), water smartweed (Persicaria amphibia), great water dock (Rumex orbiculatus), common arrowhead (Sagittaria latifolia), common skullcap (Scutellaria galericulata), Canada goldenrod (Solidago canadensis), late goldenrod (S. gigantea), swamp goldenrod (S. patula), eastern-lined aster (Symphyotrichum lanceolatum), side-flowering aster (S. lateriflorum), swamp aster (S. puniceum), purple meadow rue (Thalictrum dasycarpum), marsh St. John’s-wort (Triadenum fraseri), blue vervain (Verbena hastata), and marsh violet (Viola cucullata). Characteristic fern or fern allies include crested woodfern (Dryopteris cristata), common horsetail (Equisetum arvense), water horsetail (E. fluviatile), sensitive fern (Onoclea sensibilis), and marsh fern (Thelypteris palustris). Scattered shrub and tree species include tag alder (Alnus incana), bog birch (Betula pumila), red-osier dogwood (Cornus sericea), shrubby cinquefoil (Dasiphora fruticosa), willows (Salix spp.), meadowsweet (Spiraea alba), steeplebush (S. tomentosa), red maple (Acer rubrum), black ash (Fraxinus nigra), tamarack (Larix laricina), balsam poplar (Populus balsamifera), quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides), and northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis).

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Graminoids

- fringed brome (Bromus ciliatus)

- blue-joint (Calamagrostis canadensis)

- sedges (Carex lacustris, C. lasiocarpa, C. stricta, C. utriculata, C. vesicaria, and others)

- twig-rush (Cladium mariscoides)

- spike-rush (Eleocharis erythropoda and E. palustris)

- rattlesnake grass (Glyceria canadensis)

- marsh wild-timothy (Muhlenbergia glomerata)

- fowl meadow grass (Poa palustris)

- green bulrush (Scirpus atrovirens)

Forbs

- swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata)

- marsh bellflower (Campanula aparinoides)

- water-hemlocks (Cicuta bulbifera and C. maculata)

- swamp thistle (Cirsium muticum)

- marsh cinquefoil (Comarum palustre)

- flat-topped white aster (Doellingeria umbellata)

- downy willow-herb (Epilobium strictum)

- common boneset (Eupatorium perfoliatum)

- grass-leaved goldenrod (Euthamia graminifolia)

- joe-pye-weed (Eutrochium maculatum)

- rough bedstraw (Galium asprellum)

- bog bedstraw (Galium labradoricum)

- small bedstraw (Galium trifidum)

- jewelweed (Impatiens capensis)

- wild blue flag (Iris versicolor)

- marsh pea (Lathyrus palustris)

- cardinal flower (Lobelia cardinalis)

- great blue lobelia (Lobelia siphilitica)

- common water horehound (Lycopus americanus)

- northern bugle weed (Lycopus uniflorus)

- swamp candles (Lysimachia terrestris)

- tufted loosestrife (Lysimachia thyrsiflora)

- wild mint (Mentha canadensis)

- water smartweed (Persicaria amphibia)

- great water dock (Rumex orbiculatus)

- common arrowhead (Sagittaria latifolia)

- common skullcap (Scutellaria galericulata)

- tall goldenrod (Solidago altissima)

- Canada goldenrod (Solidago canadensis)

- late goldenrod (Solidago gigantea)

- swamp goldenrod (Solidago patula)

- rough goldenrod (Solidago rugosa)

- panicled aster (Symphyotrichum lanceolatum)

- side-flowering aster (Symphyotrichum lateriflorum)

- swamp aster (Symphyotrichum puniceum)

- purple meadow-rue (Thalictrum dasycarpum)

- marsh St. John’s-wort (Triadenum fraseri)

- broad-leaved cat-tail (Typha latifolia)

- blue vervain (Verbena hastata)

- marsh violet (Viola cucullata)

Ferns

- sensitive fern (Onoclea sensibilis)

- marsh fern (Thelypteris palustris)

Shrubs

- tag alder (Alnus incana)

- bog birch (Betula pumila)

- red-osier dogwood (Cornus sericea)

- shrubby cinquefoil (Dasiphora fruticosa)

- sweet gale (Myrica gale)

- willows (Salix spp.)

- meadowsweet (Spiraea alba)

- steeplebush (Spiraea tomentosa)

Trees

- red maple (Acer rubrum)

- tamarack (Larix laricina)

- white pine (Pinus strobus)

- balsam poplar (Populus balsamifera)

- quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides)

- northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis)

Noteworthy Animals

The late-blooming composites found in sedge meadows provide an important food source for insects, which in turn support songbirds. The hummock-hollow microtopography provides excellent nesting habitat for wetland birds. Beavers can cause substantial flooding through their dam-building activities.

Rare Plants

- Cacalia plantaginea (prairie Indian-plantain, state special concern)

- Carex wiegandii (Wiegand’s sedge, state threatened)

- Gentiana linearis (linear-leaved gentian, state threatened)

- Parnassia palustris (marsh-grass-of-Parnassus, state threatened)

- Petasites sagittatus (sweet coltsfoot, state threatened)

- Vaccinium cespitosum (dwarf bilberry, state threatened)

Rare Animals

- Alces alces (moose, state threatened)

- Asio flammeus (short-eared owl, state endangered)

- Botaurus lentiginosus (American bittern, state special concern)

- Canis lupus (gray wolf, state threatened)

- Chlidonias niger (black tern, state special concern)

- Circus cyaneus (northern harrier, state special concern)

- Cistothorus palustris (marsh wren, state special concern)

- Clemmys guttata (spotted turtle, state threatened)

- Coturnicops noveboracensis (yellow rail, state threatened)

- Emydoidea blandingii (Blanding’s turtle, state special concern)

- Gallinula chloropus (common moorhen, state special concern)

- Glyptemys insculpta (wood turtle, state special concern)

- Ixobrychus exilis (least bittern, state threatened)

- Lycaeides idas nabokovi (northern blue butterfly, state threatened)

- Lynx canadensis (lynx, state endangered)

- Phalaropus tricolor (Wilson's phalarope, state special concern)

- Pseudacris triseriata maculata (boreal chorus frog, state special concern)

- Rallus elegans (king rail, state endangered)

- Sistrurus c. catenatus (eastern massasauga, federal candidate species and state special concern)

- Sterna forsteri (Forster's tern, state special concern)

Biodiversity Management Considerations

Northern wet meadows contribute significantly to the overall biodiversity of northern Michigan and also provide ecosystem services, protecting water quality by assimilating nutrients, trapping sediment, and retaining storm and floodwaters. Protecting the hydrology of northern wet meadow is imperative for the community’s continued existence and includes avoiding surface water inputs to meadows from drainage ditches, agricultural fields, road construction, and logging in the adjacent uplands, and protecting groundwater recharge areas by maintaining native vegetation types in the uplands surrounding the community. In forested landscapes, establishing no-cut buffers around wet meadows and avoiding road construction and complete canopy removal in stands immediately adjacent to wetlands can help protect the hydrologic regime.

In fire-prone landscapes, management for wet meadow should include the use of prescribed fire. Prescribed fire can help reduce litter and woody cover, stimulate seed germination, promote seedling establishment, and bolster grass, sedge, and perennial and annual forb cover. If prescribed burning is not feasible, mowing can be used to reduce woody plant cover but should be restricted to the winter, when ground frost will reduce disturbance to soils, herbaceous plants, and hydrology, or late summer and fall when meadows are dry. Because most wetland shrubs are capable of resprouting when cut (or burned), the application of herbicides to recently cut stumps may be required to maintain open conditions.

Management should strive to prevent the establishment and spread of invasive species. Invasive species that pose a threat to the diversity and community structure of northern wet meadow include glossy buckthorn (Frangula alnus), purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), narrow-leaved cat-tail (Typha angustifolia), hybrid cat-tail (Typha xglauca), reed (Phragmites australis subsp. australis), reed canary grass (Phalaris arundinacea), common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica), and multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora). Establishment of invasive species can be prevented by maintaining the hydrologic and fire disturbance regimes and avoiding grazing. Because of the difficulty of restoring wet meadow in the absence of favorable hydrology and intact organic soils, conservation efforts should focus on protecting and managing the remaining community occurrences.

Northern wet meadows have been extensively utilized for agriculture. Prior to the 1950s, mowing for marsh hay was widely practiced. Wet meadows were frequently tiled, ditched, drained, and converted to pasture and row crops or mined for peat. The hydrology of these systems is threatened by agricultural runoff and nutrient enrichment, stream channelization, and reductions in local water tables as a result of excessive groundwater withdrawals and ditching. Lowering of the water table has caused the conversion of many sedge meadows to shrub thickets. In addition, fire suppression has allowed shrub encroachment with many sedge meadows converting to shrub thicket within ten to twenty years. Shrub encroachment is especially evident where the practice of mowing for marsh hay has been abandoned. In addition to shrub encroachment, alteration of the fire and hydrologic regimes has allowed for the invasion of sedge meadows by pernicious non-native species, especially purple loosestrife, reed canary grass, and glossy buckthorn. Sedge meadows disturbed by agricultural use, grazing, drainage, and/or filling are frequently dominated by reed canary grass, an extremely aggressive grass that forms persistent, monotypic stands.

Variation

Community structure and plant diversity can vary significantly among northern wet meadows depending on the dominant species of sedge. Wet meadows dominated by tussock sedge have complex microtopography, which fosters high levels of forb diversity. Wet meadows dominated by lake sedge typically have little microtopographic complexity and low forb diversity.

Similar Natural Communities

Emergent marsh, Great Lakes marsh, intermittent wetland, southern wet meadow, northern fen, northern shrub thicket, wet-mesic sand prairie, poor fen, and wet prairie.

Places to Visit

- Cannon Creek, Grayling State Forest Management Unit, Kalkaska Co.

- Carp River and Lake of the Clouds, Porcupine Mountains Wilderness State Park, Ontonagon Co.

- Creighton Marsh, Shingleton State Forest Management Unit, Schoolcraft Co.

- Hudson Creek, Roscommon State Forest Management Unit, Roscommon Co.

- Lost Lake, Crystal Falls State Management Unit, Dickinson Co.

- Pesheke Meadows, Van Riper State Park, Marquette Co.

Relevant Literature

- Cohen, J.G., and M.A. Kost. 2007. Natural community abstract for northern wet meadow. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 9 pp.

- Curtis, J.T. 1959. The vegetation of Wisconsin. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, WI. 657 pp.

- Eggers, S.D., and D.M. Reed. 1997. Wetland plants and plant communities of Minnesota and Wisconsin. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, St. Paul, MN. 263 pp.

- Kost, M.A., and D. De Steven. 2000. Plant community responses to prescribed burning in Wisconsin sedge meadows. Natural Areas Journal 20: 36-49.

- Peach, M., and J.B. Zedler. 2006. How tussocks structure sedge meadow vegetation. Wetlands 26(2): 322-335.

- Reuter, D.D. 1986. Sedge meadows of the upper Midwest: A stewardship summary. Natural Areas Journal 6(4): 27-34.

- Warners, D.P. 1997. Plant diversity in sedge meadows: Effects of groundwater and fire. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI. 231 pp.

For a full list of references used to create this description, please refer to the natural community abstract for Northern Wet Meadow.

More Information

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: January 23, 2026).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.