Intermittent Wetland

Overview

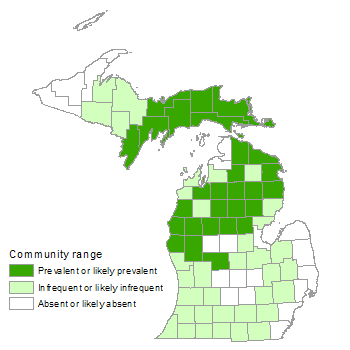

Intermittent wetland is a sedge- and herb-dominated wetland found along lakeshores or in depressions and characterized by fluctuating water levels, both seasonally and interannually. Intermittent wetlands exhibit traits of both peatlands and marshes, with characteristic vegetation including sedges (Carex spp.), rushes (Juncus spp.), sphagnum mosses, and ericaceous shrubs. The community occurs statewide.

Rank

Global Rank: G2 - Imperiled

State Rank: S3 - Vulnerable

Landscape Context

Intermittent wetlands occur throughout Michigan on poorly drained flat areas or mild depressions of sandy glacial outwash and sandy glacial lakeplain and in kettle depressions on pitted outwash. The community is found in isolated depressions and along the shores of softwater, seepage lakes and ponds where water levels fluctuate both seasonally and yearly. Intermittent wetland may be bordered by several other wetland communities and may encircle floating bog mats. The sandy, well-drained uplands surrounding intermittent wetlands typically support fire-dependent pine and oak communities.

Soils

The sandy soils underlying intermittent wetlands are strongly to very strongly acidic and are primarily sands or occasionally loamy sands. Shallow organic deposits of peat or sandy peat may overlay the sandy substrate and in some basins, a clay layer may occur below the surface.

Natural Processes

Water level fluctuations occur both seasonally and yearly within intermittent wetlands. Seasonally, water levels tend to be highest during the winter and spring and lowest in late summer and fall. The yearly oscillations are less predictable. Fluctuations of water level within intermittent wetlands allow for temporal variability of the accumulation and decomposition of organic matter. Stable periods of saturated and inundated conditions inhibit organic matter decomposition and allow for the accumulation of peat. Dam-building activities of beaver can result in blocked drainage and flooding, which facilitate sphagnum peat development and expansion. High decomposition rates within intermittent wetlands are correlated with periods of water level fluctuation, which promote oxidation and the loss of organic material that would otherwise form peat.

Water level fluctuation in intermittent wetlands facilitates seed germination and seed dispersal, and reduces competition from woody plants. Seasonal drawdowns are critical to the survival of many intermittent wetland species, especially annuals, which readily germinate from the exposed, saturated soils. Seasonal water level fluctuation also acts as an important mechanism for seed dispersal. During the winter and spring when water levels rise, seeds deposited along the low-water line float to the surface and are carried by wave action to the wetland’s outer margin. In addition, high water levels can limit tree and shrub encroachment into intermittent wetlands since prolonged flooding can result in tree and shrub mortality.

Fire is also an important component of the natural disturbance regime of intermittent wetlands. Intermittent wetlands typically occur as small depressions within a fire-dependent landscape and would have likely experienced surface fires along with the surrounding uplands when conditions were favorable. Surface fire can contribute to the maintenance of open conditions by killing encroaching trees and shrubs. In the absence of fire, a thick layer of leaf litter can develop that stifles seed germination and seedling establishment. Fire severity and frequency in intermittent wetlands is closely related to fluctuations in water level. Prolonged periods of lowered water table can allow the vegetation and surface peat to dry out sufficiently to burn. When the surface peat of intermittent wetlands burns, the fire mineralizes the peat, and kills seeds and latent buds of some species while stimulating seed germination and stem sprouting of others. Peat fires likely convert bogs to more graminoid-dominated peatlands such as intermittent wetlands, poor fens, and northern wet meadow. Because fire has been shown to increase seed germination, enhance seedling establishment, and bolster flowering, fire likely acts as an important mechanism for maintaining plant species diversity and replenishing the seed banks of intermittent wetlands.

Vegetation

Intermittent wetland is a sedge- and herb-dominated wetland. In many locations, the community borders or encompasses a bog mat that supports sphagnum mosses, low ericaceous, evergreen shrubs, and widely scattered and stunted conifer trees. The flora of intermittent wetlands is characteristically dominated by monocotyledons, with annual species contributing significantly to overall species diversity. For the majority of species, flowering and seed set occur in late summer and fall, when water levels are lowest. However, species with bog affinities found on bog mats within these wetlands tend to be spring-flowering.

Intermittent wetlands typically contain several vegetation zones, especially when they are adjacent to or encircle a lake or pond. The deepest portion of the depression is usually inundated and supports floating aquatic plants including water shield (Brasenia schreberi), yellow pond-lily (Nuphar variegata), sweet-scented water-lily (Nymphaea odorata), pondweeds (Potamogeton spp.), and bladderworts (Utricularia spp.). Occurring along the lower shores and pond margins is a seasonally flooded zone with sparse cover of low forbs and graminoids including pipewort (Eriocaulon aquaticum), bright green spike-rush (Eleocharis flavescens), Robbin’s spike-rush (E. robbinsii), autumn sedge (Fimbristylis autumnalis), brown-fruited rush (Juncus pelocarpus), beak-rushes (Rhynchospora capitellata and R. fusca), bulrushes (Schoenoplectus purshianus and S. smithii), and Torrey’s bulrush (S. torreyi, state special concern). In the saturated soil further from the shore, where the seasonal water levels typically reach their peak, is a dense graminoid-dominated zone. This is the most floristically diverse zone and typically includes species such as bluejoint grass (Calamagrostis canadensis), narrow-leaved reedgrass (C. stricta), few-seed sedge (Carex oligosperma), wiregrass sedge (C. lasiocarpa), twig-rush (Cladium mariscoides), three-way sedge (Dulichium arundinaceum), grass-leaved goldenrod (Euthamia graminifolia), wild blue flag (Iris versicolor), swamp candles (Lysimachia terrestris), ticklegrass (Agrostis scabra), and panic grass (Dichanthelium lindheimeri). Many intermittent wetlands contain a bog mat with vegetation typical of an ombrotrophic bog. These bog mats are characterized by sphagnum mosses, and low, ericaceous shrubs, with leatherleaf (Chamaedaphne calyculata) being the most prevalent. These bog mats are typically very low in herbaceous plant diversity. Trees within intermittent wetlands are typically absent or occur on the bog mat. Trees occurring on bog mats within the community are usually widely scattered and stunted conifers such as black spruce (Picea mariana) and tamarack (Larix laricina), and occasionally jack pine (Pinus banksiana) and white pine (P. strobus).

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Graminoids

- ticklegrasses (Agrostis hyemalis and A. scabra)

- blue-joint (Calamagrostis canadensis)

- wiregrass sedge (Carex lasiocarpa)

- few-seed sedge (Carex oligosperma)

- twig-rush (Cladium mariscoides)

- Eaton’s panic grass (Dichanthelium spretum)

- three-way sedge (Dulichium arundinaceum)

- bright green spike-rush (Eleocharis flavescens)

- Robbin’s spike-rush (Eleocharis robbinsii)

- autumn sedge (Fimbristylis autumnalis)

- northern manna grass (Glyceria borealis)

- Canadian rush (Juncus canadensis)

- brown-fruited rush (Juncus pelocarpus)

- beak-rushes (Rhynchospora capitellata and R. fusca)

- Pursh’s tufted bulrush (Schoenoplectus purshianus)

- Smith’s bulrush (Schoenoplectus smithii)

- Torrey’s bulrush (Schoenoplectus torreyi)

Forbs

- water-shield (Brasenia schreberi)

- spatulate-leaved sundew (Drosera intermedia)

- slender goldentop (Euthamia caroliniana)

- pipewort (Eriocaulon aquaticum)

- grass-leaved goldenrod (Euthamia graminifolia)

- northern St. John’s wort (Hypericum boreale)

- wild blue flag (Iris versicolor)

- swamp candles (Lysimachia terrestris)

- variegated yellow pond-lily (Nuphar variegata)

- sweet-scented waterlily (Nymphaea odorata)

- smartweeds (Persicaria spp.)

- pondweeds (Potamogeton spp.)

- hyssop hedge nettle (Stachys hyssopifolia)

- bushy aster (Symphyotrichum dumosum)

- horned bladderwort (Utricularia cornuta)

- humped bladderwort (Utricularia gibba)

- purple bladderwort (Utricularia purpurea)

- small purple bladderwort (Utricularia resupinata)

- lance-leaved violet (Viola lanceolata)

Mosses

- sphagnum mosses (Sphagnum spp.)

Shrubs

- leatherleaf (Chamaedaphne calyculata)

- meadowsweet (Spiraea alba)

- steeplebush (Spiraea tomentosa)

Trees

- tamarack (Larix laricina)

- black spruce (Picea mariana)

- jack pine (Pinus banksiana)

- red pine (Pinus resinosa)

- white pine (Pinus strobus)

Noteworthy Animals

Beaver (Castor canadensis) and muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus) can profoundly influence the hydrology of intermittent wetlands. Muskrats create open water channels through peat, and beavers can cause substantial flooding through their dam-building activities.

Rare Plants

- Bartonia paniculata (panicled screw-stem, state threatened)

- Carex nigra (black sedge, state endangered)

- Carex wiegandii (Wiegand's sedge, state threatened)

- Eleocharis melanocarpa (black-fruited spike-rush, state special concern)

- Gratiola virginiana (round-fruited hedge hyssop, state threatened)

- Hemicarpha micrantha (dwarf bulrush, state special concern)

- Huperzia selago (fir clubmoss, state special concern)

- Juncus vaseyi (Vasey’s rush, state threatened)

- Juncus militaris (bayonet rush, state threatened)

- Ludwigia alternifolia (seedbox, state special concern)

- Lycopodiella margueriteae (northern prostrate clubmoss, state special concern)

- Lycopodiella subappressa (northern appressed clubmoss, state threatened)

- Polygonum careyi (Carey's smartweed, state threatened)

- Potamogeton bicupulatus (waterthread pondweed, state threatened)

- Pycnanthemum verticillatum (whorled mountain mint, state special concern)

- Ranunculus cymbalaria (seaside crowfoot, state threatened)

- Sabatia angularis (rose pink, state threatened)

- Schoenoplectus torreyi (Torrey's bulrush, state special concern)

- Scirpus clintonii (Clinton’s bulrush, state special concern)

- Scirpus torreyi (Torrey’s bulrush, state special concern)

Rare Animals

- Alces alces (moose, state threatened)

- Appalachia arcana (secretive locust, state special concern)

- Ardea herodias (great blue heron, protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918)

- Asio flammeus (short-eared owl, state endangered)

- Boloria freija (Freija fritillary, state special concern)

- Boloria frigga (Frigga fritillary, state special concern)

- Botaurus lentiginosus (American bittern, state special concern)

- Canis lupus (gray wolf, state threatened)

- Circus cyaneus (northern harrier, state special concern)

- Clemmys guttata (spotted turtle, state threatened)

- Coturnicops noveboracensis (yellow rail, state threatened)

- Elaphe o. obsoleta (black rat snake, state special concern)

- Emydoidea blandingii (Blanding’s turtle, state special concern)

- Erebia discoidalis (red-disked alpine, state special concern)

- Falco columbarius (merlin, state threatened)

- Gallinula chloropus (common moorhen, state special concern)

- Gavia immer (common loon, state threatened)

- Haliaeetus leucocephalus (bald eagle, state threatened)

- Ixobrychus exilis (least bittern, state threatened)

- Lynx canadensis (lynx, state endangered)

- Merolonche dolli (Doll’s merolonche moth, state special concern)

- Pandion haliaetus (osprey, state threatened)

- Phalaropus tricolor (Wilson's phalarope, state special concern)

- Rallus elegans (king rail, state endangered)

- Sistrurus c. catenatus (eastern massasauga, federal candidate species and state special concern)

- Somatochlora incurvata (incurvate emerald, state special concern)

- Terrapene c. carolina (eastern box turtle, state special concern)

- Williamsonia fletcheri (ebony boghaunter, state special concern)

Biodiversity Management Considerations

Protection of the regional and local hydrologic regime is critical to the preservation of intermittent wetlands. Stabilization of water levels can allow for the establishment of perennials and woody species, which can displace less competitive annuals. Increased surface flow and alteration of groundwater recharge can be prevented by avoiding road construction and complete canopy removal in adjacent stands. A serious threat to intermittent wetland hydrology and species diversity is posed by off-road vehicle (ORV) traffic, which can significantly alter the hydrology through rutting and erosion. Soil erosion resulting from ORV use within the wetland or surrounding uplands may greatly disturb the seed bank, reducing plant density and diversity. Reduction of access to wetland systems will help decrease detrimental impacts from ORVs.

Where shrub and tree encroachment threatens to convert open wetlands to shrub-dominated systems or forested swamps, prescribed fire can be employed to maintain open conditions. Prescribed fires are best employed in intermittent wetlands during droughts or in the late summer and fall when water levels are lowest. In addition to controlling woody invasion, fire promotes seed bank expression and rejuvenation and thus helps maintain species diversity. Intermittent wetlands are common natural features within a variety of droughty, fire-dependent, upland pine and oak matrix communities and would likely have experienced surface fires along with the surrounding uplands when conditions were favorable. When feasible, prescribed fires conducted in the adjacent uplands should be allowed to carry into intermittent wetlands.

Monitoring and control efforts to detect and remove invasive species are critical to the long-term viability of intermittent wetland. Invasive species that threaten the diversity and community structure of intermittent wetlands include reed (Phragmites australis subsp. australis), reed canary grass (Phalaris arundinacea), narrow-leaved cat-tail (Typha angustifolia), hybrid cat-tail (Typha xglauca), purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), glossy buckthorn (Frangula alnus), and multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora).

Variation

Species composition of intermittent wetlands varies depending on fluctuating water levels and fire disturbance.

Similar Natural Communities

Bog, coastal plain marsh, emergent marsh, northern fen, northern wet meadow, and poor fen.

Places to Visit

- Baraga Plains, Baraga Plains State Waterfowl Management Area, Baraga Co.

- Dagget Lake Wetlands and Norris Road Wetland, Barry State Game Area, Barry Co.

- Duck Lake, Atlanta State Forest Management Unit, Cheboygan Co.

- Frog Lakes, Grayling State Forest Management Unit, Crawford Co.

- Michaud Lake, Shingleton State Forest Management Unit, Schoolcraft Co.

- Swamp Lakes, Newberry State Forest Management Unit and The Nature Conservancy (Swamp Lakes Preserve), Luce Co.

Relevant Literature

- Boelter, D.H., and E.S. Verry. 1977. Peatland and water in the northern Lake States. North Central Forest Experiment Station. USDA, Forest Service General Technical Report NC-31. 26 pp.

- Cohen, J.G., and M.A. Kost. 2007. Natural community abstract for intermittent wetland. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 11 pp.

- Gates, F.C. 1942. The bogs of northern Lower Michigan. Ecological Monographs 12(3): 213-254.

- van der Valk, A.G. 1986. The impact of litter and annual plants on recruitment from the seed bank of a lacustrine wetland. Aquatic Botany 24: 13-26.

- Zoltai, S.C., and D.H. Vitt. 1995. Canadian wetlands: Environmental gradients and classification. Vegetatio 118: 131-137.

For a full list of references used to create this description, please refer to the natural community abstract for Intermittent Wetland.

More Information

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: March 6, 2026).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.