Open Dunes

Overview

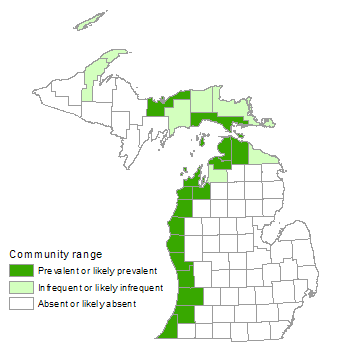

Open dunes is a grass- and shrub-dominated multi-seral community located on wind-deposited sand formations near the shorelines of the Great Lakes. Dune formation and the patterning of vegetation are strongly affected by lake-driven winds. The greatest concentration of open dunes occurs along the eastern and northern shorelines of Lake Michigan, with the largest dunes along the eastern shoreline due to the prevailing southwest winds.

Rank

Global Rank: G3 - Vulnerable

State Rank: S3 - Vulnerable

Landscape Context

Dune formation is a dynamic, cyclic process that appears to be linked to high water levels in the Great Lakes. An early period of dune formation coincided with Glacial Lake Algonquin (approximately 11,000 years ago). During the Nipissing period (4,000 to 6,000 years ago), when Great Lakes levels were considerably higher than today, the Grand Sable Dunes on Lake Superior and the Nordhouse Dunes along northern Lake Michigan formed. Other Lake Michigan dune complexes, including those near Muskegon and Grand Haven, were formed during high-water periods as recently as 3,000 years ago. Characteristic topographic features of most sand dunes include beaches, foredunes, high dunes, perched dunes, dune fields, interdunal swales, and blowouts. The slope on the windward face of dunes is gentle, usually not more than 15 degrees. On the lee or back side of the dune, the slope is much steeper and may reach the “angle of repose” of dry sand. Open dunes are typically nestled within a forested landscape, with the dune sands supporting a variety of forest types depending on slope, aspect, and geographic location; southern forest types are restricted to the southern Lower Peninsula but northern types such as mesic northern forest may occur on dune sands both north and south of the climatic tension zone.

Soils

Dune sand consists largely of quartz (87-94%), with lesser amounts of feldspar (10-18%), magnetite (1-3%), and traces of other minerals, such as calcite, garnet, and hornblende. Sand particles are rounded and frosted by continuous collisions with other sand grains. Because the sand contains calcareous minerals, it is neutral to slightly alkaline.

Natural Processes

A combination of water erosion and wind deposition resulted in the formation of Great Lakes coastal dunes. The sand source for the coastal dunes was glacial sediment that was eroded by streams and by waves eroding bluffs along the Great Lakes shoreline. These sediments were then moved along the Great Lakes shoreline by nearshore currents, and then deposited along the shoreline by wave action. Strong winds then carried the sands inland, creating dunes.

Dune vegetation is adapted to constant sand burial and abrasion. As plants are buried by sand, they continue to form new growth above the sand while their roots and rhizomes continue to grow and stabilize the sand. As vegetation of the dunes is stabilized, herb and shrub diversity increases, and there is a gradual accumulation of organic soils and eventual transition to forest. At the forest edge, colonizers include oak in the southern part of the state and pine in both the north and south. When lake levels recede, beach and dune areas increase, permitting lakeward expansion of savanna and forest, but when lake levels rise, blowouts expand into the forest. The open, dry conditions of the sand dunes provided ideal conditions for the establishment of fire-dependent oaks and pines. Lightning fires ignited patches of dune grasses and leaf litter, allowing these fire-dependent savanna and forest communities to persist at the borders of the open dune.

Vegetation

Dominant species and community structure vary depending on degree of sand deposition, sand erosion, and distance from the lake. The beach is dominated by annuals, including sea rocket (Cakile edentula). Depositional areas, such as foredunes, are dominated by marram grass (Ammophila breviligulata). Erosional areas, such as slacks in blowouts and dune fields, are dominated by sand reed grass (Calamovilfa longifolia), while more stabilized areas are dominated by little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium). In dune fields and on the most stable dune ridges, low evergreen shrubs like bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi) and creeping juniper (Juniperus horizontalis) occupy dune crests. Less frequent dominants include sand cherry (Prunus pumila), willows (Salix cordata, S. serissima, and S. myricoides), and common juniper (Juniperus communis). Characteristic dune species include sea rocket, beach pea (Lathyrus japonicus), seaside spurge (Euphorbia polygonifolia), marram grass, sand reed grass, little bluestem, plains puccoon (Lithospermum caroliniense), Pitcher’s thistle (Cirsium pitcheri, federal/state threatened), Lake Huron tansy (Tanacetum bipinnatum, state threatened), wormwood (Artemisia campestris), harebell (Campanula rotundifolia), common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca), sand cherry, red-osier dogwood (Cornus sericea), willows, common juniper, quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides), and balsam poplar (P. balsamifera). Approximately 25-35% of open dunes species also grow on maritime dunes (e.g., sea rocket, marram grass, beach heath [Hudsonia tomentosa], and beach pea). The many western plant species set open dunes apart, as do its endemic plants.

All dunes have distinctive zones (beach, foredune, interdunal wetland or trough, and backdune) determined largely by the physical processes of dune formation: transport of sand along the shore by waves and current, followed by wind-transport of sand to create dunes. The beach is the most dynamic zone, where wind, waves, and coastal currents create an ever-changing environment. Scattered plants of sea rocket are often found growing near the water’s edge. Farther up the beach, plants tolerant of strong winds and high temperatures, such as beach pea and seaside spurge, are able to establish. The foredune is the zone where pioneering grasses, especially marram grass, allow sand to accumulate, enabling additional plants to establish. Eventually the grasses, herbs, and shrubs stabilize the sand enough that larger backdunes form behind the foredune. Backdunes are often forested, but blowouts occasionally occur. Open sand within the blowout is soon colonized by dune grasses, which stabilize the sand and facilitate the formation of an open dune community.

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Graminoids

- marram grass (Ammophila breviligulata)

- sand reed grass (Calamovilfa longifolia)

- rough sand sedge (Cyperus schweinitzii)

- wheat grasses (Elymus lanceolatus and E. trachycaulus)

- Rocky Mountain fescue (Festuca saximontana)

- June grass (Koeleria macrantha)

- switch grass (Panicum virgatum)

- little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium)

Forbs

- red anemone (Anemone multifida)

- sand cress (Arabidopsis lyrata)

- wormwood (Artemisia campestris)

- common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca)

- sea rocket (Cakile edentula)

- harebell (Campanula rotundifolia)

- Pitcher’s thistle (Cirsium pitcheri )

- sand coreopsis (Coreopsis lanceolata)

- bugseeds (Corispermum americanum and C. pallasii)

- flowering spurge (Euphorbia corollata)

- seaside spurge (Euphorbia polygonifolia)

- beach pea (Lathyrus japonicus)

- plains puccoon (Lithospermum caroliniense)

- starry false Solomon-seal (Maianthemum stellatum)

- horse mint (Monarda punctata)

- jointweed (Polygonella articulata)

- silverweed (Potentilla anserina)

- Gillman’s goldenrod (Solidago simplex)

- Lake Huron tansy (Tanacetum bipinnatum)

Woody Vines

- American bittersweet (Celastrus scandens)

- poison-ivy (Toxicodendron radicans)

- riverbank grape (Vitis riparia)

Shrubs

- bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi)

- bunchberry (Cornus canadensis)

- round-leaved dogwood (Cornus rugosa)

- red-osier dogwood (Cornus sericea)

- shrubby cinquefoil (Dasiphora fruticosa)

- beach heath (Hudsonia tomentosa)

- common juniper (Juniperus communis)

- creeping juniper (Juniperus horizontalis)

- sand cherry (Prunus pumila)

- hop tree (Ptelea trifoliata)

- wild roses (Rosa acicularis and R. blanda)

- pasture rose (Rosa carolina)

- willows (Salix cordata, S. exigua, and S. myricoides)

- poison-ivy (Toxicodendron rydbergii)

- blueberries (Vaccinium angustifolium and V. myrtilloides)

Trees

- balsam fir (Abies balsamea)

- paper birch (Betula papyrifera)

- white ash (Fraxinus americana)

- white spruce (Picea glauca)

- pines (Pinus banksiana, P. resinosa, and P. strobus)

- balsam poplar (Populus balsamifera)

- cottonwood (Populus deltoides)

- big-toothed aspen (Populus grandidentata)

- quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides)

- red oak (Quercus rubra)

- black oak (Quercus velutina)

- sassafras (Sassafras albidum)

- northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis)

- basswood (Tilia americana)

Noteworthy Animals

Many animals of the dunes are adapted to the extreme surface temperatures of the dune, which regularly reach 120o F (50o C) and locally reach 180o F (80o C). To survive such extremes, dune inhabitants like Fowler’s toad (Bufo fowleri), eastern hognose snake (Heterodon platyrhinos), spider wasps (Family Pompilidae), and wolf spiders (Family Lycosidae) burrow down to reach cooler temperatures and are active at the surface only from evening to morning, when the temperatures are lower. Antlions (Family Myrmeleontidae) have adapted to the environment by building funnel-shaped sand traps where insects and ants become trapped.

Rare Plants

- Adlumia fungosa (climbing fumitory, state special concern)

- Botrychium acuminatum (acute-leaved moonwort, state endangered)

- Botrychium campestre (prairie moonwort, state threatened)

- Botrychium hesperium (western moonwort, state threatened)

- Botrychium mormo (goblin moonwort, state threatened)

- Bromus pumpellianus (Pumpelly’s brome grass, state threatened)

- Calypso bulbosa (calypso, state threatened)

- Carex concinna (beauty sedge, state special concern)

- Carex platyphylla (sedge, state threatened)

- Carex seorsa (sedge, state threatened)

- Cirsium hillii (Hill’s thistle, state special concern)

- Cirsium pitcheri (Pitcher’s thistle, federal/state threatened)

- Crataegus douglasii (Douglas’s hawthorn, state special concern)

- Cypripedium arietinum (ram’s head lady’s-slipper, state special concern)

- Danthonia intermedia (wild oatgrass, state special concern)

- Elymus mollis (American dune wild-rye, state special concern)

- Galearis spectabilis (showy orchis, state threatened)

- Hieracium paniculatum (panicled hawkweed, state special concern)

- Huperzia selago (fir clubmoss, state special concern)

- Iris lacustris (dwarf lake iris, federal/state threatened)

- Listera auriculata (auricled twayblade, state threatened)

- Orobanche fasciculata (fascicled broom-rape, state threatened)

- Panax quinquefolius (ginseng, state threatened)

- Polygonum careyi (Carey’s smartweed, state threatened)

- Sabatia angularis (rose pink, state threatened)

- Salix pellita (satiny willow, state special concern)

- Solidago houghtonii (Houghton’s goldenrod, federal/state threatened)

- Stellaria longipes (stitchwort, state special concern)

- Tanacetum huronense (Lake Huron tansy, state threatened)

- Triplasis purpurea (sand grass, state special concern)

- Trisetum spicatum (downy oat-grass, state special concern)

- Vitis vulpina (frost grape, state threatened)

Rare Animals

- Charadrius melodus (piping plover, federal/state endangered)

- Dendroica discolor (prairie warbler, state endangered)

- Euxoa aurulenta (dune cutworm, state special concern)

- Sterna caspia (Caspian tern, state threatened)

- Sterna hirundo (common tern, state threatened)

- Trimerotropis huroniana (Lake Huron locust, state threatened)

Biodiversity Management Considerations

Major threats to open dunes include off-road vehicles, recreational overuse, residential development, sand mining, and invasive plants and animals. While blowouts are a natural occurrence, their frequency is greatly exacerbated by human activities that erode vegetation cover. Off-road vehicles and recreational overuse can destroy plants that stabilize dunes, leading to large blowouts during heavy storms and significantly reducing vegetation cover from both massive wind erosion and burial of existing flora and fauna. Eliminating illegal off-road vehicle activity is a primary means of protecting the ecological integrity of open dunes and associated shoreline communities. Residential development destroys dune habitat, results in introductions of invasive plants, and prevents natural dune movement, which many dune plants require. In addition, roaming pets disrupt ground-nesting birds, some of which are globally rare. Sand mining directly destroys dunes. Invasive plants can eliminate native dune plants through competition for resources and by stabilizing dunes, which results in the loss of plants that rely on shifting sand and facilitates conversion to closed-canopy forest. Invasive plants that threaten the diversity and community structure in open dunes include spotted knapweed (Centaurea stoebe), baby’s breath (Gypsophila paniculata), common St. John’s-wort (Hypericum perforatum), ox-eye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare), bull thistle (Cirsium vulgare), white sweet clover (Melilotus alba), common mullein (Verbascum thapsus), black swallow-wort (Vincetoxicum nigrum), white swallow-wort (Vincetoxicum rossicum), hoary alyssum (Berteroa incana), Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis), Canada bluegrass (P. compressa), quack grass (Elymus repens), timothy (Phleum pratense), hawkweeds (Hieracium spp.), sheep sorrel (Rumex acetosella), black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia), white poplar (Populus alba), Lombardy poplar (P. nigra var. italica), common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica), autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata), Eurasian honeysuckles (especially Lonicera morrowii, L. tatarica, and L. xbella), and multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora). Monitoring and control efforts to detect and remove invasive species are critical to the long-term viability of open dunes.

Variation

Four distinctive types of dunes occur in Michigan: parabolic, perched, linear, and transverse. Parabolic and perched dunes support open, herb- and shrub-dominated plant communities, while linear and transverse dunes are often forested. Parabolic dunes, large complexes of U-shaped dunes up to 300 ft high along eastern Lake Michigan, formed 11,000 to 13,000 years ago during high lake levels. Perched dunes rest on morainal bluffs along eastern Lake Michigan and southeastern Lake Superior. While the morainal bluffs can be 27 to 110 m (90 to 360 ft) high, the perched dunes are much smaller. Linear dunes, or dune and swale complexes, are arcuate (i.e., curving) complexes of roughly parallel dune ridges separated by narrow swales that formed as Great Lakes water levels receded. Typical linear dunes are only about 3 to 5 m (10 to 15 ft) high and 9 to 30 m (30 to 100 ft) wide. Transverse dunes, linear to scalloped in shape, formed in shallow bays along the edge of the glaciers 11,000 years ago. Strong winds blew off the glaciers, forming a series of long, linear dunes, oriented perpendicularly to the wind. They are generally 9 to 18 m (30 to 60 ft) high with a steep south face and are surrounded by shallow peatlands. Various types of open dune are found in all of the Great Lakes states and provinces, including Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and the Canadian province of Ontario. Vermont also has sand dunes along Lake Champlain.

Similar Natural Communities

Great Lakes barrens, pine barrens, oak-pine barrens, interdunal wetland, sand and gravel beach, wooded dune and swale complex, and dry sand prairie.

Places to Visit

- Grand Mere, Grand Mere State Park, Berrien Co.

- Grand Sable Dunes, Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore, Alger Co.

- Muskegon Dunes, Muskegon State Park, Muskegon Co.

- Nordhouse Dunes, Ludington State Park and Manistee National Forest, Mason Co.

- North Manitou Island, Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, Leelanau Co.

- P. J. Hoffmaster State Park, Ottawa Co. and Muskegon Co.

- Point Betsie, The Nature Conservancy (Zetterberg Preserve at Point Betsie), Benzie Co.

- Pyramid Point, Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, Leelanau Co.

- Saugatuck Dunes, Saugatuck Dunes State Park, Allegan Co.

- Sleeping Bear Dunes, Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, Leelanau Co.

- South Manitou Island, Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, Leelanau Co.

- Warren Dunes, Warren Dunes State Park, Berrien Co.

Relevant Literature

- Albert, D.A. 1999. Natural community abstract for open dunes. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 5 pp.

- Albert, D.A. 2000. Borne of the wind: An introduction to the ecology of Michigan sand dunes. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 63 pp.

- Arbogast, A.F., and W.L. Loope. 1999. Maximum-limiting ages of Lake Michigan coastal dunes: Their correlation with Holocene lake level history. Journal of Great Lakes Research 25: 372-383.

- Cowles, H.C. 1899. The ecological relations of the vegetation on the sand dunes of Lake Michigan. Botanical Gazette 27(2): 95-117.

- Faber-Langendoen, D., ed. 2001. Plant communities of the Midwest: Classification in an ecological context. Association for Biodiversity Information, Arlington, VA. 61 pp. + appendix (705 pp.).

- Guire, K.E., and E.G. Voss. 1963. Distribution of distinctive plants in the Great Lakes region. Michigan Botanist 2: 99-114.

- Lichtner, J. 1998. Primary succession and forest development on coastal Lake Michigan sand dunes. Ecological Monographs 68: 487-510.

- Olson, J. 1958. Rates of succession and soil changes on southern Lake Michigan sand dunes. Botanical Gazette 119: 125-170.

- Thompson, T.A. 1992. Beach-ridge development and lake-level variation in southern Lake Michigan. Sedimentary Geology 80: 305-318.

For a full list of references used to create this description, please refer to the natural community abstract for Open Dunes.

More Information

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: March 2, 2026).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.