Overview

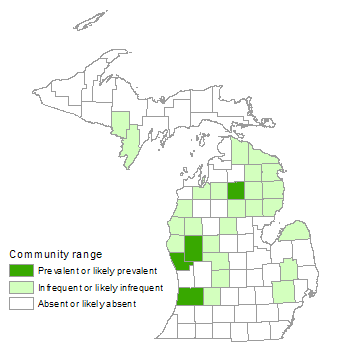

Oak-pine barrens is a fire-dependent, savanna community dominated by oaks and pines, having between 5 and 60% canopy cover, with or without a shrub layer. The predominantly graminoid ground layer contains plant species associated with both prairie and forest. The community occurs on a variety of landforms on droughty, infertile sand or loamy sands occasionally within southern Lower Michigan but mostly north of the climatic tension zone in the northern Lower and Upper Peninsulas.

Rank

Global Rank: G3 - Vulnerable

State Rank: S2 - Imperiled

Landscape Context

Oak-pine barrens occur on nearly level to slightly undulating ground in well-drained sandy glacial outwash, sandy glacial lakeplains, and less often on sandy areas in coarse-textured moraines. The community occurs in the driest landscape positions, such as ridge tops, steep slopes, south- to west-facing slopes, and flat sandplains. Oak-pine barrens typically grade into dry sand prairie on one edge and dry forest on the other. Wetlands occurring within depressions in areas of oak-pine barrens are usually open and may include coastal plain marsh, intermittent wetland, bog, poor fen, wet meadow, and northern fen.

Soils

Soils of oak-pine barrens are typically infertile, excessively well-drained sand or loamy sand with medium to slightly acid pH and low water-retaining capacity. Soils range from coarse-textured loam sands on moraines to very fine-textured sands on lakeplains. The soils contain little organic matter and are droughty.

Natural Processes

Oak-pine barrens likely originated when prairie fires spread into surrounding closed oak and pine forest with enough intensity to create open barrens. Repeated low-intensity fires working in concert with drought, frost, and windthrow maintained barrens ecosystems. Fires prevented canopy closure and the dominance of woody vegetation. Fires in oak-pine barrens and prairies occur during the spring, late summer, and fall. Flammability peaks bimodally, in the spring before grass and forb growth resumes and in the late summer and autumn after the above-ground biomass dies. Infrequent, high-intensity fires kill mature oaks and pines and produce barrens covered by abundant scrubby oak sprouts (i.e., oak grubs). In addition to fire, frequent growing-season frosts prevent maturation of oak grubs. Park-like barrens with widely spaced trees and an open grass understory are maintained by frequent, low-intensity fires that occur often enough to restrict maturation of oak grubs.

Numerous biotic factors influence the patterning of vegetation of oak-pine barrens. In addition to widely distributed overstory trees, barrens are characterized by scattered ant mounds. Mound-building ants play a crucial role in soil development of prairies and barrens; ants mix and aerate the soil as they build tunnels and bring soil particles and nutrients to the topsoil from lower soil horizons. Herbivores can limit woody establishment and growth. With their flammable properties, grasses and forbs help maintain the annual fire regime. Open canopy conditions are also preserved by the development of a dense herbaceous litter, which limits tree seedling establishment. Overstory trees influence vegetative composition by affecting the distribution of nutrients, light, and moisture.

Vegetation

The canopy layer generally varies from 5 to 60% cover and is dominated or codominated by the following trees: white oak (Quercus alba), black oak (Q. velutina), northern pin oak (Q. ellipsoidalis), bur oak (Q. macrocarpa), white pine (Pinus strobus), red pine (P. resinosa), and jack pine (P. banksiana). These pine and oak species are also prevalent in the subcanopy as multi-stemmed shrubs of stump-sprout origin, especially where fire intensity is high. Additional tree species found in the overstory and subcanopy include red maple (Acer rubrum), black cherry (Prunus serotina), big-toothed aspen (Populus grandidentata), and quaking aspen (P. tremuloides). Characteristic shrubs include the following: serviceberry (Amelanchier spp.), bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi), New Jersey tea (Ceanothus americanus), sweetfern (Comptonia peregrina), alternate-leaved dogwood (Cornus alternifolia), flowering dogwood (C. florida), American hazelnut (Corylus americana), beaked hazelnut (C. cornuta), hawthorn species (Crataegus spp.), huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata), wild plum (Prunus americana), choke cherry (P. virginiana), sand cherry (P. pumila), dwarf chinquapin oak (Quercus prinoides), pasture rose (Rosa carolina), northern dewberry (Rubus flagellaris), prairie willow (Salix humilis), and low sweet blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium). The ground layer is dominated by graminoids and forbs. Dominant species include little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), and Pennsylvania sedge (Carex pensylvanica). Pennsylvania sedge often replaces the bluestems in shaded areas and fire-suppressed communities, especially north of the transition zone. Other prevalent herbs of oak-pine barrens include false foxglove (Aureolaria spp.), hair grass (Avenella flexuosa), tickseed (Coreopsis lanceolata), poverty grass (Danthonia spicata), flowering spurge (Euphorbia corollata), woodland sunflower (Helianthus divaricatus), white pea (Lathyrus ochroleucus), hairy bush clover (Lespedeza hirta), dwarf blazing star (Liatris cylindracea), wild lupine (Lupinus perennis), wild bergamot (Monarda fistulosa), wood betony (Pedicularis canadensis), black oatgrass (Piptochaetium avenaceum), and prairie heart-leaved aster (Symphyotrichum oolentangiense). The flora of this community is a mixture of prairie and forest species, with prairie forbs and grasses more abundant in open areas and forest forbs and woody species more common in shaded areas.

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Graminoids

- big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii)

- fork-tipped three-awned grass (Aristida basiramea)

- three-awned grass (Aristida purpurascens)

- wavy hair grass (Avenella flexuosa)

- Pennsylvania sedge (Carex pensylvanica)

- slender sand sedge (Cyperus lupulinus)

- poverty grass (Danthonia spicata)

- panic grasses (Dichanthelium spp.)

- fall witch grass (Digitaria cognata)

- purple love grass (Eragrostis spectabilis)

- porcupine grass (Hesperostipa spartea)

- June grass (Koeleria macrantha)

- black oatgrass (Piptochaetium avenaceum)

- little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium)

Forbs

- pussytoes (Antennaria howellii and A. parlinii)

- wormwood (Artemisia campestris)

- milkweeds (Asclepias amplexicaulis, A. syriaca, A. tuberosa, and A. viridiflora)

- false foxgloves (Aureolaria flava, a. pedicularia, and A. virginica)

- harebell (Campanula rotundifolia)

- Hill’s thistle (Cirsium hillii)

- sand coreopsis (Coreopsis lanceolata)

- common rockrose (Crocanthemum canadense)

- prairie cinquefoil (Drymocallis arguta)

- flowering spurge (Euphorbia corollata)

- wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana)

- woodland sunflower (Helianthus divaricatus)

- western sunflower (Helianthus occidentalis)

- hawkweeds (Hieracium kalmii and H. venosum)

- long-leaved bluets (Houstonia longifolia)

- false dandelion (Krigia biflora)

- dwarf dandelion (Krigia virginica)

- hairy bush-clover (Lespedeza hirta)

- rough blazing-star (Liatris aspera)

- cylindrical blazing-star (Liatris cylindracea)

- northern blazing-star (Liatris scariosa)

- hoary puccoon (Lithospermum canescens)

- hairy puccoon (Lithospermum caroliniense)

- wild lupine (Lupinus perennis)

- wild bergamot (Monarda fistulosa)

- horse mint (Monarda punctata)

- blue toadflax (Nuttallanthus canadensis)

- prickly-pear (Opuntia humifusa)

- wood-betony (Pedicularis canadensis)

- prairie phlox (Phlox pilosa)

- racemed milkwort (Polygala polygama)

- jointweed (Polygonella articulata)

- early buttercup (Ranunculus fascicularis)

- goldenrods (Solidago caesia, S. hispida, S. juncea, S. nemoralis, and S. speciosa)

- prairie heart-leaved aster (Symphyotrichum oolentangiense)

- yellow-pimpernel (Taenidia integerrima)

- goats-rue (Tephrosia virginiana)

- birdfoot violet (Viola pedata)

Ferns

- bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum)

Shrubs

- serviceberries (Amelanchier spp.)

- bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi)

- New Jersey tea (Ceanothus americanus)

- sweetfern (Comptonia peregrina)

- hazelnuts (Corylus americana and C. cornuta)

- huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata)

- American plum (Prunus americana)

- sand cherry (Prunus pumila)

- choke cherry (Prunus virginiana)

- pasture rose (Rosa carolina)

- northern dewberry (Rubus flagellaris)

- prairie willow (Salix humilis)

- low sweet blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium)

Trees

- red maple (Acer rubrum)

- juneberry (Amelanchier arborea)

- flowering dogwood (Cornus florida)

- hawthorns (Crataegus spp.)

- jack pine (Pinus banksiana)

- red pine (Pinus resinosa)

- white pine (Pinus strobus )

- big-toothed aspen (Populus grandidentata)

- quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides)

- black cherry (Prunus serotina)

- white oak (Quercus alba)

- northern pin oak (Quercus ellipsoidalis)

- black oak (Quercus velutina)

Noteworthy Animals

Oak-pine barrens and surrounding prairie habitat once supported a rich diversity of invertebrates including numerous species of butterflies, skippers, grasshoppers, and locusts. Mound-building ants and numerous grassland birds also thrived in barrens and prairies. The fragmented and degraded status of Midwestern oak-pine barrens, savannas, and prairies has resulted in the drastic decline of numerous insect and bird species associated with savanna habitats and prairie/savanna host plants. Where large-scale herbivores were abundant, grazing may have helped inhibit the succession of oak-pine barrens to woodland and forest.

Rare Plants

- Antennaria parvifolia (pussy-toes, state special concern)

- Artemisia ludoviciana (western mugwort, state threatened)

- Asclepias ovalifolia (dwarf milkweed, state endangered)

- Aster sericeus (western silvery aster, state threatened)

- Bouteloua curtipendula (side-oats grama grass, state threatened)

- Carex tincta (sedge, state special concern)

- Cirsium hillii (Hill’s thistle, state special concern)

- Festuca scabrella (rough fescue, state threatened)

- Geum triflorum (prairie-smoke, state threatened)

- Linum sulcatum (furrowed flax, state special concern)

- Prunus alleghaniensis var. davisii (Alleghany plum, state special concern)

Rare Animals

- Ammodramus savannarum (grasshopper sparrow, state special concern)

- Atrytonopsis hianna (dusted skipper, state threatened)

- Catocala amestris (three-staff underwing, state endangered)

- Cryptotis parva (least shrew, state threatened)

- Dendroica discolor (prairie warbler, state endangered)

- Elaphe o. obsoleta (black rat snake, state special concern)

- Erynnis p. persius (Persius duskywing, state threatened)

- Hesperia ottoe (ottoe skipper, state threatened)

- Incisalia henrici (Henry’s elfin, state special concern)

- Incisalia irus (frosted elfin, state threatened)

- Lepyronia gibbosa (Great Plains spittlebug, state threatened)

- Lycaeides melissa samuelis (Karner blue, federal endangered and state threatened)

- Microtus ochrogaster (prairie vole, state endangered)

- Oecanthus pini (pinetree cricket, state special concern)

- Orphulella p. pelidna (barrens locust, state special concern)

- Papaipema sciata (Culver’s root borer, state special concern)

- Prosapia ignipectus (red-legged spittlebug, state special concern)

- Pygarctia spraguei (Sprague’s pygarctia, state special concern)

- Pyrgus centaureae wyandot (grizzled skipper, state special concern)

- Schinia indiana (phlox moth, state endangered)

- Schinia lucens (leadplant flower moth, state endangered)

- Scudderia fasciata (pine katydid, state special concern)

- Sistrurus c. catenatus (eastern massasauga, federal candidate species and state special concern)

- Speyeria idalia (regal fritillary, state endangered)

- Terrapene c. carolina (eastern box turtle, state special concern)

Biodiversity Management Considerations

Fire is the single most significant factor in preserving oak-pine barrens landscapes. Where remnants of oak-pine barrens persist, the use of prescribed fire is an imperative management tool for maintaining an open canopy, promoting high levels of grass and forb diversity, deterring the encroachment of woody vegetation and invasive species, and limiting the success of canopy dominants. Fire intervals of one to three years bolster graminoid dominance, increase overall grass and forb diversity, and remove woody cover of saplings and shrubs. Burning at longer time intervals will allow for woody plant seedling establishment and persistence. Where rare species are a management concern, burning strategies should allow for ample refugia to facilitate effective post-burn recolonization. Fire management should be orchestrated in conjunction with that of adjacent fire-dependent upland and wetland communities such as dry sand prairie, coastal plain marsh, pine barrens, and dry northern forest. Degraded barrens that have been long deprived of fire often contain a heavy overstory component of shade-tolerant species, which can be removed by mechanical thinning or girdling. Restored sites can be maintained by periodic prescribed fire and may require investment in native plant seeding where seed and plant banks are inadequate.

Historically, Native Americans played an integral role in fire regimes of barrens ecosystems, intentionally and/or accidentally setting fire to savanna, barrens, and prairie ecosystems. Destructive timber exploitation of pines (1890s) and oaks (1920s) combined with post-logging slash fires and attempts to farm the droughty soils destroyed or degraded oak-pine barrens across Michigan. In addition, alteration of the historical fire regime has shifted many of the vegetation types with barrens physiognomy into woodlands and forest. Fire suppression policies instituted in the 1920s resulted in the succession of open oak-pine barrens to closed-canopy forests dominated by black and white oaks with little advanced regeneration of oaks and pines and a vanishing graminoid component. Many sites formerly occupied by oak-pine barrens were also converted to pine plantations. The oak-pine barrens fragments that remain are often lacking the full complement of conifers, which were ubiquitously harvested. In addition to simplified overstory structure, these communities are often depauperate in floristic diversity as the result of fire suppression, livestock grazing, off-road vehicle activity, and the subsequent invasion of non-native species.

Monitoring and control efforts to detect and remove invasive species are critical to the long-term viability of oak-pine barrens. Invasive species that threaten the diversity and community structure of oak-pine barrens, especially in southern Lower Michigan, include common St. John’s-wort (Hypericum perforatum), spotted knapweed (Centaurea stoebe), black swallow-wort (Vincetoxicum nigrum), white swallow-wort (V. rossicum), Canada bluegrass (Poa compressa), ox-eye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare), hoary alyssum (Berteroa incana), common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica), autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata), Eurasian honeysuckles (especially Lonicera morrowii, L. tatarica, and L. xbella), and multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora).

Variation

The oak-pine barrens community is a heterogeneous savanna community with variable physiognomy in time and space. Structurally, oak-pine barrens range from dense thickets of brush and understory scrub oak and pine among a matrix of grassland to park-like woodlands of widely spaced mature oaks and pines with virtually no tall-shrub or subcanopy layer above the open forb and graminoid-dominated ground flora. The physiognomic variations, which occur along a continuum, are the function of the complex interplay between fire frequency, fire intensity, and site factors (soils, landform, slope, aspect, etc).

Along the climatic tension zone and to the south, the most common overstory dominants are white oak, black oak, and white pine. North of the tension zone, northern pin oak replaces black oak, and red pine and jack pine become more prevalent in the canopy layer.

Similar Natural Communities

Bur oak plains, dry sand prairie, dry southern forest, dry northern forest, Great Lakes barrens, lakeplain oak openings, oak openings, oak barrens, and pine barrens.

Places to Visit

- Allegan Oak-Pine Barrens, Allegan State Game Area, Allegan Co.

- Shakey Lakes, Escanaba State Forest Management Unit, Menominee Co.

- Sleeper Barrens, Albert E. Sleeper State Park and Rush Lake State Game Area, Huron Co.

Relevant Literature

- Chapman, K.A., M.A. White, M.R. Huffman and D. Faber-Langendoen. 1995. Ecology and stewardship guidelines for oak barrens landscapes in the upper Midwest. In Proceedings of the Midwest Oak Savanna Conference, 1993, ed. F. Stearns and K. Holland. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Internet Publications.

- Cohen, J.G. 2000. Natural community abstract for oak-pine barrens. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 6 pp.

- Faber-Langendoen, D. 1993. A proposed classification for savannas in the Midwest. Background paper for the Midwest Oak Savanna Conference. 18 pp.

- Faber-Langendoen, D., and M.A. Davis. 1995. Effects of fire frequency on tree canopy cover at Allison Savanna, eastcentral Minnesota, USA. Natural Areas Journal 15(4): 319-328.

- Nuzzo, V. 1986. Extent and status of Midwest oak savanna: Presettlement and 1985. Natural Areas Journal 6: 6-36.

- Peterson, D.W., and P.B. Reich. 2001. Prescribed fire in oak savanna: Fire frequency effects on stand structure and dynamics. Ecological Applications 11(3): 914-927.

- Tester, J.R. 1989. Effects of fire frequency on oak savanna in east-central Minnesota. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 116(2): 134-144.

- White, A.S. 1983. The effects of thirteen years of annual prescribed burning on a Quercus ellipsoidalis community in Minnesota. Ecology 64(5): 1081-108.

- Will-Wolf, S., and F. Stearns. 1999. Dry soil oak savanna in the Great Lakes region. Pp. 135-154 in Savannas, barrens, and rock outcrop plant communities of North America, ed. R.C. Anderson, J.S. Fralish, and J.M. Baskin. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 480 pp.

For a full list of references used to create this description, please refer to the natural community abstract for Oak-Pine Barrens.

More Information

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: December 30, 2025).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.