Mesic Southern Forest

Overview

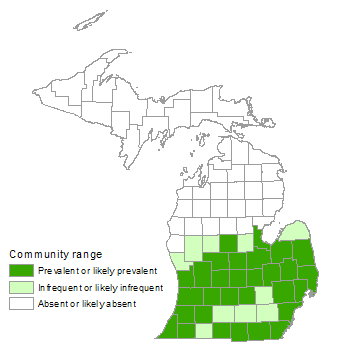

Mesic southern forest is an American beech- and sugar maple-dominated forest distributed south of the climatic tension zone and found on flat to rolling topography with predominantly loam soils. The natural disturbance regime is characterized by gap-phase dynamics; frequent, small windthrow gaps allow for the regeneration of shade-tolerant, canopy species. Historically, mesic southern forest occurred as a matrix system, dominating vast areas of rolling to level, loamy uplands of the Great Lakes region. These forests were multi-generational, with old-growth conditions lasting many centuries.

Rank

Global Rank: G2G3 - Rank is uncertain, ranging from imperiled to vulnerable

State Rank: S3 - Vulnerable

Landscape Context

Mesic southern forest is found principally on medium- or fine-textured ground moraine, medium- or fine-textured end moraine, and on silty/clayey glacial lakeplains. Sand dunes and sandy lakeplains can support these systems where proximity to the Great Lakes modifies the local climate. The community can also occur on ice-contact topography and coarse-textured end moraines, as well as floodplain terraces in a diversity of landforms. Prevalent topographic positions of this community are gentle to moderate slopes and low, level areas with moderate to good drainage.

Soils

The community occurs on a variety of soil types, but loam is the predominant texture. Soils supporting mesic southern forest include sand, sandy loam, loamy sand, loam, silt loam, silty clay loam, clay loam, and clay. Soils are typically well-drained with high water-holding capacity and high nutrient and soil organism content. High soil fertility is maintained by nutrient inputs from the decomposition of deciduous leaves and coarse woody debris. Where American beech is dominant in the canopy, its leaf litter can have a podzolizing effect on the soil, increasing the acidity. Soil pH ranges widely from slightly acidic to moderately alkaline.

Natural Processes

The natural disturbance regime of mesic southern forest is characterized by frequent small-scale wind disturbance or gap-phase dynamics and infrequent, intermediate- to large-scale wind events. Severe low pressure systems generate small-scale canopy gaps, while catastrophic windthrow associated with tornadoes and downbursts can impact large areas. In addition to wind disturbance, glaze or ice storms are a significant source of intermediate disturbance, thinning the canopy and promoting tree regeneration over hundreds to thousands of acres. Approximately 1% of the total area of mesic forest is within recent gap (less than one year old) and the average canopy residence time ranges between 50 and 200 years. Frequent small-scale disturbance events generate a forest mosaic of different-aged patches of gaps of a wide range of sizes; the majority of gaps are between 100 and 400 square meters. Small-scale disturbance events are the primary source of forest turnover. Recruitment of saplings within treefall gaps is typically by shade-tolerant species (primarily sugar maple and American beech) that can exist suppressed beneath the closed canopy for decades. Due to the long interval between large-scale disturbances, mesic southern forests tend to be multi-generational, with old-growth conditions lasting several centuries. Old-growth conditions include a high quantity of dead wood (snags, stumps, and fallen logs) in a diversity of ages, sizes, and stages of decomposition, high basal area, large diameter canopy dominants, multilayered canopies, numerous canopy gaps of diverse age and size, and pit and mound microtopography from continual, frequent windthrow. Historically, where mesic southern forest bordered fire-dependent prairie, savanna, and oak woodland systems, it is likely that low-intensity surface fires occasionally burned portions of the ground layer and helped promote diversity by releasing nutrients and exposing a mineral soil seedbed.

Vegetation

Principal dominants of the canopy are American beech (Fagus grandifolia) and sugar maple (Acer saccharum), which together often make up over 80% of the canopy composition. Canopy associates include bitternut hickory (Carya cordiformis), white ash (Fraxinus americana), tulip tree (Liriodendron tulipifera), white oak (Quercus alba), red oak (Q. rubra), and basswood (Tilia americana). American elm (Ulmus americana) and ironwood (Ostrya virginiana) are common in the subcanopy. Sugar maple is the overwhelming dominant within the understory layer and often the ground layer. American beech, elm, and ironwood are also common saplings. Common shrub species include pawpaw (Asimina triloba), musclewood (Carpinus caroliniana), alternate-leaved dogwood (Cornus alternifolia), flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), leatherwood (Dirca palustris), witch hazel (Hamamelis virginiana), spicebush (Lindera benzoin), American fly honeysuckle (Lonicera canadensis), prickly gooseberry (Ribes cynosbati), red elderberry (Sambucus racemosa), and maple-leaved arrow-wood (Viburnum acerifolium). Common vines include Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia), green briar (Smilax spp.), and poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans). The ground flora is characterized by a prevalence of spring ephemerals, high diversity, and high degree of compositional similarity across its range. Common ground flora include spring beauty (Claytonia virginica), cut-leaved toothwort (Cardamine concatenata), squirrel corn (Dicentra canadensis), Dutchman’s breeches (D. cucullaria), white trout lily (Erythronium albidum), yellow trout lily (E. americanum), false rue anemone (Enemion biternatum), doll’s eyes (Actaea pachypoda), jack-in-the-pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum), wild ginger (Asarum canadense), blue cohosh (Caulophyllum thalictroides), wild geranium (Geranium maculatum), sharp-lobed hepatica (Hepatica acutiloba), Virginia waterleaf (Hydrophyllum virginianum), may apple (Podophyllum peltatum), bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis), common trillium (Trillium grandiflorum), large-flowered bellwort (Uvularia grandiflora), maidenhair fern (Adiantum pedatum), wild leek (Allium tricoccum), sedges (Carex albursina and C. plantaginea), enchanter’s nightshade (Circaea canadensis), beech drops (Epifagus virginiana), and running strawberry bush (Euonymus obovata).

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Graminoids

- autumn bent (Agrostis perennans)

- sedges (Carex albursina, C. arctata, C. blanda, C. communis, C. gracilescens, C. grisea, C. hirtifolia, C. jamesii, C. pedunculata, C. plantaginea, C. rosea, C. woodii, and others)

- nodding fescue (Festuca subverticillata)

- wood millet (Milium effusum)

- bluegrasses (Poa alsodes and P. sylvestris)

Forbs

- baneberries (Actaea pachypoda and A. rubra)

- wild leeks (Allium burdickii and A. tricoccum)

- Jack-in-the-pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum)

- wild ginger (Asarum canadense)

- cut-leaved toothwort (Cardamine concatenata)

- blue cohoshes (Caulophyllum giganteum and C. thalictroides)

- enchanter’s-nightshade (Circaea canadensis)

- spring beauty (Claytonia virginica)

- squirrel-corn (Dicentra canadensis)

- Dutchman’s breeches (Dicentra cucullaria)

- false rue anemone (Enemion biternatum)

- beech drops (Epifagus virginiana)

- harbinger-of-spring (Erigenia bulbosa)

- yellow trout lily (Erythronium americanum)

- false mermaid (Floerkea proserpinacoides)

- wild geranium (Geranium maculatum)

- sharp-lobed hepatica (Hepatica acutiloba)

- great waterleaf (Hydrophyllum appendiculatum)

- Canada waterleaf (Hydrophyllum canadense)

- Virginia waterleaf (Hydrophyllum virginianum)

- pale touch-me-not (Impatiens pallida)

- wood nettle (Laportea canadensis)

- Canada mayflower (Maianthemum canadense)

- false spikenard (Maianthemum racemosum)

- bishop’s-cap (Mitella diphylla)

- hairy sweet cicely (Osmorhiza claytonii)

- dwarf ginseng (Panax trifolius)

- May apple (Podophyllum peltatum)

- downy Solomon seal (Polygonatum pubescens)

- white lettuces (Prenanthes alba and P. altissima)

- bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis)

- upright carrion-flower (Smilax ecirrata)

- bluestem goldenrod (Solidago caesia)

- common trillium (Trillium grandiflorum)

- large-flowered bellwort (Uvularia grandiflora)

- violets (Viola spp.)

Ferns

- maidenhair fern (Adiantum pedatum)

- lady fern (Athyrium filix-femina)

- rattlesnake fern (Botrypus virginianus)

- silvery spleenwort (Deparia acrostichoides)

- spinulose woodfern (Dryopteris carthusiana)

- Goldie’s woodfern (Dryopteris goldiana)

- evergreen woodfern (Dryopteris intermedia)

- marginal woodfern (Dryopteris marginalis)

- narrow-leaved spleenwort (Homalosorus pycnocarpos)

- broad beech-fern (Phegopteris hexagonoptera)

- Christmas fern (Polystichum acrostichoides)

- New York fern (Thelypteris noveboracensis)

Woody Vines

- Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia)

- greenbriers (Smilax spp.)

- poison-ivy (Toxicodendron radicans)

- riverbank grape (Vitis riparia)

Shrubs

- leatherwood (Dirca palustris)

- witch hazel (Hamamelis virginiana)

- spicebush (Lindera benzoin)

- Canadian fly honeysuckle (Lonicera canadensis)

- prickly gooseberry (Ribes cynosbati)

- red elderberry (Sambucus racemosa)

- maple-leaved arrow-wood (Viburnum acerifolium)

Trees

- sugar maple (Acer saccharum)

- pawpaw (Asimina triloba)

- musclewood (Carpinus caroliniana)

- bitternut hickory (Carya cordiformis)

- shagbark hickory (Carya ovata)

- alternate-leaved dogwood (Cornus alternifolia)

- flowering dogwood (Cornus florida)

- American beech (Fagus grandifolia)

- white ash (Fraxinus americana)

- tulip tree (Liriodendron tulipifera)

- ironwood (Ostrya virginiana)

- black cherry (Prunus serotina)

- white oak (Quercus alba)

- chinquapin oak (Quercus muehlenbergii)

- red oak (Quercus rubra)

- basswood (Tilia americana)

- American elm (Ulmus americana)

Noteworthy Animals

Large contiguous tracts of old-growth and mature mesic southern forest provide important habitat for cavity nesters, species of detritus-based food webs, canopy-dwelling species, and interior forest obligates, including numerous neotropical migrants such as black-throated green warbler (Dendroica virens), scarlet tanager (Piranga olivacea), and ovenbird (Seiurus aurocapillus). Vernal pools within mesic southern forests provide critical habitat for reptiles and amphibians.

Rare Plants

- Adlumia fungosa (climbing fumitory, state special concern)

- Aristolochia serpentaria (Virginia snakeroot, state threatened)

- Carex oligocarpa (eastern few-fruited sedge, state threatened)

- Carex platyphylla (broad-leaved sedge, state threatened)

- Castanea dentata (American chestnut, state endangered)

- Dentaria maxima (large toothwort, state threatened)

- Euphorbia commutata (tinted spurge, state threatened)

- Galearis spectabilis (showy orchis, state threatened)

- Gentianella quinquefolia (stiff gentian, state threatened)

- Hybanthus concolor (green violet, state special concern)

- Hydrastis canadensis (goldenseal, state threatened)

- Jeffersonia diphylla (twinleaf, state special concern)

- Liparis liliifolia (purple twayblade, state special concern)

- Ophioglossum vulgatum (southeastern adder’s tongue, state threatened)

- Panax quinquefolius (ginseng, state threatened)

- Polymnia uvedalia (large-flowered buttercup, state threatened)

- Ruellia strepens (smooth ruellia, state threatened)

- Scutellaria elliptica (hairy skullcap, state special concern)

- Scutellaria ovata (heart-leaved skullcap, state threatened)

- Smilax herbacea (smooth carrion-flower, state special concern)

- Tipularia discolor (cranefly orchid, state threatened)

- Trillium recurvatum (prairie trillium, state threatened)

- Trillium sessile (sessile trillium, state threatened)

- Triphora trianthophora (three-birds orchid, state threatened)

- Viburnum prunifolium (black haw, state special concern)

- Vitis vulpina (frost grape, state threatened).

Rare Animals

- Accipiter cooperii (Cooper’s hawk, state special concern)

- Accipiter gentilis (northern goshawk, state special concern)

- Ambystoma opacum (marbled salamander, state threatened)

- Ambystoma texanum (small-mouthed salamander, state endangered)

- Buteo lineatus (red-shouldered hawk, state threatened)

- Dendroica cerulea (cerulean warbler, state special concern)

- Dryobius sexnotatus (six-banded longhorn beetle, state special concern)

- Elaphe o. obsoleta (black rat snake, state special concern)

- Emydoidea blandingii (Blanding’s turtle, state special concern)

- Microtus pinetorum (woodland vole, state special concern)

- Nerodia erythrogaster neglecta (copperbelly watersnake, federal threatened and state endangered)

- Nicrophorus americanus (American burying beetle, federal/state endangered)

- Protonotaria citrea (prothonotary warbler, state special concern)

- Seiurus motacilla (Louisiana waterthrush, state special concern)

- Terrapene c. carolina (eastern box turtle, state special concern)

- Wilsonia citrina (hooded warbler, state special concern)

Biodiversity Management Considerations

When the primary conservation objective is to maintain or enhance biodiversity in mesic southern forests, the most appropriate management is to leave large tracts (especially old-growth and late-successional forest) unharvested and allow natural processes to operate unhindered. Conservation and restoration of fragmented mesic forest communities require active, long-term management of deer at low densities. Where resources are available, deer exclosures may be erected around concentrations of sensitive herbs and susceptible saplings. Intensive management may also be required to control non-native species invasion in fragments of mesic southern forest. Limiting anthropogenic disturbance in large tracts of old-growth and mature mesic southern forest is the best means of reducing the possibility of invasive species establishment and domination. Much of Michigan’s mesic southern forest is immature and has not yet attained the structural and compositional features of old-growth mesic forest. Mimicking gap-dominated disturbances and promoting dead tree dynamics can hasten old-growth, uneven-aged conditions in immature and mature stands. Forest continuity can be maximized by retaining large-diameter snags, coarse woody debris, and old, living trees.

Intensive and pervasive anthropogenic disturbance during the past 150 years has altered the extent, landscape pattern, natural processes, structure, and species composition of mesic southern forest. Mesic southern forest, especially old-growth and late-successional forest, has been drastically reduced in acreage. This formerly matrix community type is now fragmented, with most old-growth and late-successional stands persisting as remnant patches enmeshed in a matrix of agricultural lands. The structure and composition of the remnants have been altered by selective logging, grazing, removal of snags and logs for firewood, deer herbivory, non-native species invasion, and introduced diseases and insect outbreaks (e.g., Dutch elm disease, chestnut blight, beech bark disease, and emerald ash borer). Structural alterations include the reduction of large-diameter trees, snags, and coarse woody debris and invasion of non-native shrubs and ground flora. Many fragments are dominated solely by sugar maple, which was often left to provide maple syrup and is favored in gaps created by selective logging. In addition, American beech was often culled because of its poor timber value. Conversely, many stands that were high-graded of valuable timber (i.e., sugar maple and red oak) are now beech-dominated. Chronically high deer densities have limited tree recruitment and altered floral composition and structure. Herbs of this community are highly susceptible to herbivory by deer. Herbaceous plants constitute 87% of deer’s summer diet and often suffer from reduced flowering rates, survivorship, plant size, and extirpation due to herbivory by this keystone herbivore. Indirect impacts of deer herbivory can include the reduction of pollinators and seed dispersers of sensitive herbs. Nest predation by edge species and nest parasitism (mainly by cowbirds) increase with forest fragmentation and account for population declines of forest birds, especially neotropical migrants.

Monitoring and control activities to detect and remove invasive species are critical to the long-term viability of mesic southern forest. Invasive plant species that threaten the diversity and community structure in mesic southern forest include garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata), Dame’s rocket (Hesperis matronalis), Oriental bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus), Eurasian honeysuckles (Lonicera morrowii, L. japonica, L. maackii, L. tatarica, L. xbella, and L. xylosteum), Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii), common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica), glossy buckthorn (Frangula alnus), multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora), autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata), common privet (Ligustrum vulgare), European highbush cranberry (Viburnum opulus), and Norway maple (Acer platanoides).

Variation

Three physiographic subtypes of mesic southern forest occur in Michigan: one on the level, eastern lakeplains, one on the western sand dunes, and one on the glacial outwash plains and moraines between these areas.

Similar Natural Communities

Mesic northern forest, dry-mesic southern forest, southern hardwood swamp, floodplain forest, and wet-mesic flatwoods.

Places to Visit

- Baker Woodlot, Michigan State University, Ingham Co.

- Crane Hills, Crane Pond State Game Area, Cass Co.

- Grand Valley Ravines, Grand Valley State College, Ottawa Co.

- Haven Hill, Highland State Recreation Area, Oakland Co.

- Russ Forest, Michigan State University, Cass Co.

- Sanford Woods, Michigan State University, Ingham Co.

- Sharon Hollow, The Nature Conservancy (Nan Weston Nature Preserve at Sharon Hollow, Washtenaw Co.

- Warren Dunes, Warren Dunes State Park, Berrien Co.

- Warren Woods, Warren Woods State Park, Berrien Co.

Relevant Literature

- Augustine, D.J., and L.E. Frelich. 1998. Effects of white-tailed deer on populations of an understory forb in fragmented deciduous forests. Conservation Biology 12(5): 995-1004.

- Benninghoff, W.S., and A.I. Gebben. 1960. Phytosociological studies of some beech-maple stands in Michigan’s Lower Peninsula. Papers of the Michigan Academy of Science, Arts, and Letters 45: 83-91.

- Brewer, R., and P.J. Merritt. 1978. Windthrow and tree replacement in a climax beech-maple forest. Oikos 30: 149-152.

- Cohen, J.G. 2004. Natural community abstract for mesic southern forest. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 12 pp.

- Heske, E.J., S.K. Robinson, and J.D. Brawn. 2001. Nest predation and neotropical migrant songbirds: Piecing together the fragments. Wildlife Society Bulletin 29(1): 52-61.

- Poulson, T.L., and W.J. Platt. 1996. Replacement patterns of beech and sugar maple in Warren Woods, Michigan. Ecology 77(4): 1234-1253.

- Rogers, R.S. 1981. Early spring herb communities in mesophytic forests of the Great Lakes region. Ecology 63(4): 1050-1063.

- Runkle, J.R. 1991. Gap dynamics of old-growth eastern forests: Management implications. Natural Areas Journal 11(1): 19-25.

- Woods, K.D. 1979. Reciprocal replacement and the maintenance of codominance in a beech-maple forest. Oikos 33: 31-39.

For a full list of references used to create this description, please refer to the natural community abstract for Mesic Southern Forest.

More Information

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: January 23, 2026).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.