Submergent Marsh

Overview

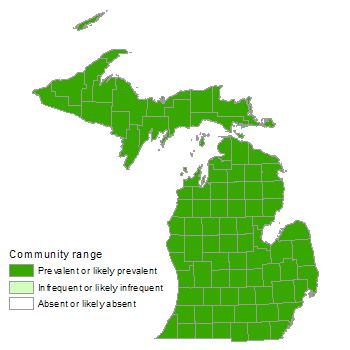

Submergent marsh is an herbaceous plant community that occurs in deep to sometimes shallow water in lakes and streams throughout Michigan. Soils are characterized by loosely consolidated organics of variable depth that range from acid to alkaline and accumulate over all types of mineral soil, even bedrock. Submergent vegetation is composed of both rooted and non-rooted submergent plants, rooted floating-leaved plants, and non-rooted floating plants. Common submergent plants include common waterweed (Elodea canadensis), water star-grass (Heteranthera dubia), milfoils (Myriophyllum spp.), naiads (Najas spp.), pondweeds (Potamogeton spp.), stoneworts (Chara spp. and Nitella spp.), coontail (Ceratophyllum demersum), bladderworts (Utricularia spp.), and water-celery (Vallisneria americana).

Rank

Global Rank: GU - Unrankable

State Rank: S4 - Apparently secure

Landscape Context

Submergent marsh occurs as a zone along the shore of large lakes, or it can cover the entire surface of small, shallow lakes and ponds. In clear lakes, submergent vegetation can persist in water greater than ten meters deep. Submergent vegetation can also form dense beds along the margins of slow-moving streams, or form open, less diverse plant beds in more rapidly flowing streams.

Soils

Loose, poorly consolidated organic soils characterize most submergent plant beds, which can establish on almost all types of mineral soil, and even over bedrock. Such organic soils can be meters thick and are often easily eroded by boat traffic. In the more acid, low nutrient lakes, the accumulation of organic sediments can be minimal, but this is quite variable. The pH of organic sediments can range from acid to alkaline and is largely dependent on the pH of the lake or stream water and underlying mineral substrate.

Natural Processes

Natural water-level fluctuations, fauna, storm waves, and currents all create conditions important for plant regeneration. For example, water shield (Brasenia schreberi) produces seed only when water levels drop, leaving plants stranded, and submergent bulrush (Schoenoplectus subterminalis) only fruits when water levels are shallow enough for it to produce emergent stems. Establishment of submergent plants is also affected by substrate changes initiated by fish nests and waterfowl feeding; these openings and depressions created by fauna create substrate and light heterogeneity that facilitate plant colonization. Beaver play an integral role in the creation and maintenance of submergent marshes as the community often establishes along channels and ponds generated by beaver flooding. Storm waves and currents are important for distributing seeds and asexual propagules, as well as altering sediment conditions.

Vegetation

Dominant plants include both rooted and non-rooted submergent plants, rooted floating-leaved plants, and non-rooted floating plants. Some of the more widely distributed rooted submergent plants are common waterweed, water star-grass, milfoils, naiads, pondweeds (nearly 30 species), water crowfoots, water-celery, and stoneworts. A few submergent plants are non-rooted, including the extremely widespread coontail and several of the carnivorous bladderworts (Utricularia vulgaris, U. intermedia, and U. gibba). Most observers are familiar with the showy rooted floating-leaved plants, which include sweet-scented water-lily (Nymphaea odorata), yellow pond-lily (Nuphar variegata and N. advena), and water shield (Brasenia schreberi). Some of the less conspicuous plants of the submergent marsh are the non-rooted floating plants, including small duckweeds (Lemna minor, L. turionifera, and L. trisulca), great duckweed (Spirodela polyrhiza), and water meal (Wolffia spp.).

Submergent marshes can exhibit distinct zonation. Floating-leaved waterlilies and yellow pond-lilies are often concentrated along the shallow organic-rich margins of submergent marshes, while pondweeds, including Potamogeton amplifolius, P. praelongus, P. illinoensis, P. zosteriformis, P. friesii, and P. strictifolius can grow in water five meters deep or greater. Other submergent plants of the deep marsh include wild celery and common waterweed. The stoneworts, actually green algae, are able to persist in far deeper water than most flowering aquatic plants, often forming a low, lawn-like mat to as much as 40 meters below the surface.

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Submergent Plants

- coontail (Ceratophyllum demersum )

- muskgrasses (Chara spp.)

- common waterweed (Elodea canadensis)

- pipewort (Eriocaulon aquaticum)

- water star-grass (Heteranthera dubia)

- water-milfoils (Myriophyllum spp.)

- naiads (Najas flexilis, and others)

- stoneworts (Nitella spp.)

- pondweeds (Potamogeton friesii, P. praelongus, P. strictifolius, P. zosteriformis, Stuckenia spp., and others)

- submergent bulrush (Schoenoplectus subterminalis)

- bladderworts (Utricularia spp.)

- water-celery (Vallisneria americana)

Rooted Floating-leaved Plants

- water-shield (Brasenia schreberi)

- yellow pond-lilies (Nuphar advena and N. variegata)

- sweet-scented waterlily (Nymphaea odorata)

- pondweeds (Potamogeton amplifolius, P. illinoensis, and others)

Non-rooted Floating Plants

- small duckweed (Lemna minor)

- star duckweed (Lemna trisulca)

- red duckweed (Lemna turionifera)

- great duckweed (Spirodela polyrhiza)

- water meals (Wolffia spp.)

Noteworthy Animals

Submergent marshes provide habitat to a broad diversity of aquatic invertebrates, many of which occupy and feed on decomposing vegetation. The invertebrates support numerous species of fish, amphibians, reptiles, waterfowl, water birds, and wetland mammals like muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus). Muskrats and beaver (Castor canadensis) can profoundly influence the hydrology of submergent marshes and surrounding wetlands. Muskrats create open water channels and beavers can cause substantial flooding through their dam-building activities. Specific submergent plants can be critical to fauna. For example, loss of water-celery from the Detroit River resulted in major declines in redheads (Aythya americana) and other diving ducks.

Rare Plants

- Lemna valdiviana (pale duckweed, presumed extirpated from Michigan)

- Littorella uniflora (American shore-grass, state special concern)

- Myriophyllum alterniflorum (alternate-leaved water-milfoil, state special concern)

- Potamogeton confervoides (alga pondweed, state special concern)

- Potamogeton pulcher (spotted pondweed, state threatened)

- Potamogeton vaseyi (Vasey’s pondweed, state threatened)

- Ruppia maritima (widgeon-grass, state threatened)

- Subularia aquatica (awlwort, state endangered)

Rare Animals

- Lepisosteus oculatus (spotted gar, state special concern)

Biodiversity Management Considerations

Maintaining low levels of boat traffic and eliminating nutrient and sediment inputs, dredging activity, and invasive species populations is integral to protecting the ecological integrity of high quality submergent marsh. Especially on small northern lakes, motorboat propellers and the discharge from jet skis and personal watercraft can disturb the loose substrates of submergent marshes, eventually eliminating vegetation. Zebra mussels have altered the chemistry of many aquatic habitats, modifying habitat for aquatic plants, often increasing the amount of submergent vegetation in turbid, nutrient-rich waters. Invasive aquatic plants such as Eurasian water-milfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum) now dominate portions of many lakes and slow-flowing rivers throughout Michigan, especially in the Lower Peninsula. Its dense growth can result in the loss of other aquatic plant species, eliminate habitat for fish, invertebrates, and wildlife, and degrade water quality. Another aggressive invasive aquatic, frogbit (Hydrocharis morsus-ranae), is currently known from only a few locations in southeastern Michigan and one location in the eastern Upper Peninsula, and efforts to restrict its spread should be undertaken while its distribution in Michigan is still limited. Similarly, hydrilla (Hydrilla verticillata) has aggressively colonized submergent marshes and outcompeted native submergent plants in nearby states, highlighting the importance of monitoring to prevent its spread in Michigan waterways. Propagules of aquatic plants are often unintentionally spread by watercraft moving among lakes and rivers, and boaters are strongly encouraged to inspect and rinse their boats after use. Both native and invasive aquatic plants can respond with increased growth to nutrient input in the form of runoff from agricultural fields and lawns, leaking septic systems, and sewage discharge. Long-term, increased nutrient inputs can lead to lake eutrophication, algal blooms, and loss of aquatic plant and animal diversity. Dredging for marl has destroyed many marshes along the edges of small lakes in the eastern Upper Peninsula and portions of Lower Michigan.

Variation

A shallow water type in northern softwater, acid lakes is composed of several rosette-forming species, such as pipewort (Eriocaulon aquaticum), quillwort (Isoetes spp.), American shore-grass (Littorella uniflora, state special concern), brown-fruited rush (Juncus pelocarpus f. submersus), water lobelia (Lobelia dortmanna), and water-milfoil (Myriophyllum tenellum). Great Lakes coastal marshes often contain a zone of submergent vegetation in deeper water, beyond the emergent marsh zone.

Similar Natural Communities

Emergent marsh, intermittent wetland, and Great Lakes marsh.

Places to Visit

- Forked Lake Marsh, Crane Pond State Game Area, Cass Co.

- Lake of the Clouds, Porcupine Mountains Wilderness State Park, Ontonagon Co.

- Otis Lake Marsh, Barry State Game Area, Barry Co.

Relevant Literature

- Albert, D.A. 2003. Between land and lake: Michigan’s Great Lakes coastal wetlands. Michigan Natural Features Inventory. Michigan State University Extension, East Lansing, MI. Bulletin E-2902. 96 pp.

- Cronk, J.K., and M. Siobhan Fennessy. 2001. Wetland plants: Biology and ecology. Lewis Publishers, Boca Raton, FL. 462 pp.

- Faber-Langendoen, D., ed. 2001. Plant communities of the Midwest: Classification in an ecological context. Association for Biodiversity Information, Arlington, VA. 61 pp. + appendix (705 pp.).

- Hutchinson, G.E. 1975. A treatise on limnology. Volume 3. Limnological botany. John Wiley and Sons, New York, NY. 660 pp.

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: March 14, 2026).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.