Interdunal Wetland

Overview

Interdunal wetland is a rush-, sedge-, and shrub-dominated wetland situated in depressions within open dunes or between beach ridges along the Great Lakes, experiencing a fluctuating water table seasonally and yearly in synchrony with lake level changes.

Rank

Global Rank: G2? - Imperiled (inexact)

State Rank: S2 - Imperiled

Landscape Context

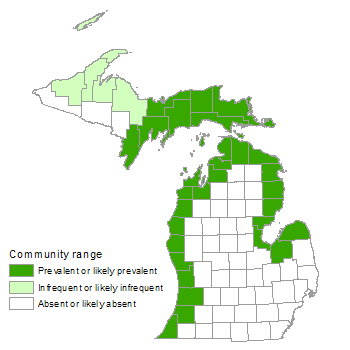

This natural community is typically found in long troughs or swales between dune ridges, in wind-formed depressions at the base of blowouts, in hollows of dune fields, and in abandoned river channels that once flowed parallel to the lakeshore behind a foredune. Interdunal wetlands occur on all of the Laurentian Great Lakes.

Soils

The saturated sand and pond water of interdunal wetlands along the lower Great Lakes is neutral to moderately alkaline because of traces of calcareous minerals in the lake-edge sands. The sand, which is sometimes covered by a thin layer of muck, is similar in composition to that of the surrounding beach ridges or dunes, consisting largely of quartz with lesser amounts of feldspar, magnetite, and traces of other minerals, such as calcite, garnet, and hornblende. On Lake Superior, there is little or no calcite, and alkalinity is typically lower than in the other Great Lakes. In the Straits of Mackinac region, the underlying soil in interdunal wetlands is sometimes fine-textured loams or clays rich in calcium carbonate. Carbonate-rich groundwater flows from adjacent sand dunes or nearby limestone or dolomite uplands, providing nutrients for rapid growth of stonewort (Chara spp.) and other algae. The metabolism of these algae produces calcium carbonate, which precipitates as a fine, white mud-like substance called marl. As marl deposits accumulate, sometimes reaching more than a meter in depth, they facilitate the formation of northern fen.

Natural Processes

The water-level fluctuations of the adjacent Great Lakes are important for the dynamics of the interdunal wetlands. Interdunal wetlands are formed when water levels of the Great Lakes drop, creating a swale or linear depression between the inland foredune and the newly formed foredune along the water’s edge. When Great Lakes water levels rise or during storm events, the interdunal wetland closest to the shoreline can be partially or completely buried by sand. Summer heating and evaporation can result in warm, shallow water or even complete drying within the swale. Where shallow standing water overlays fine-textured substrates within the swales, precipitation of calcium carbonate in the form of marl is common.

Vegetation

The data used for this description are almost exclusively from narrow interdunal wetlands along the Great Lakes shoreline, with little data from hollows or depressions in dune fields and no data from large inland lakes. Dominant plants include Baltic rush (Juncus balticus) and twig-rush (Cladium mariscoides), both species able to survive sand burial and water level fluctuations. Some other common plants are Kalm’s lobelia (Lobelia kalmii), horned bladderwort (Utricularia cornuta), common bog arrow-grass (Triglochin maritima), Kalm’s St. John’s-wort (Hypericum kalmianum), false asphodel (Triantha glutinosa), golden-seeded spike-rush (Eleocharis elliptica), grass-leaved goldenrod (Euthamia graminifolia), shrubby cinquefoil (Dasiphora fruticosa), three-square (Schoenoplectus pungens), bluejoint grass (Calamagrostis canadensis), beak-rush (Rhynchospora capillacea), and seedling or shrub-sized northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis). Other typical species include several sedges (Carex aquatilis, C. garberi, C. viridula, C. lasiocarpa, and C. stricta), small-fringed gentian (Gentianopsis virgata), blue-leaf willow (Salix myricoides), geocaulon (Geocaulon lividum), purple gerardia (Agalinis purpurea), balsam ragwort (Packera paupercula), Houghton’s goldenrod (Solidago houghtonii, federal/state threatened), Ohio goldenrod (S. ohioensis), silverweed (Potentilla anserina), grass-of-Parnassus (Parnassia glauca), scouring rush (Equisetum variegatum), sweet gale (Myrica gale), tamarack (Larix laricina), spike-rush (Eleocharis quinqueflora), hardstem bulrush (Schoenoplectus acutus), pitcher-plant (Sarracenia purpurea), sand dune willow (Salix cordata), Indian paintbrush (Castilleja coccinea), swamp candles (Lysimachia terrestris), dwarf Canadian primrose (Primula mistassinica), smooth scouring rush (Equisetum laevigatum), red-osier dogwood (Cornus sericea), low calamint (Clinopodium arkansanum), tag alder (Alnus incana), ticklegrass (Agrostis scabra), marsh cinquefoil (Comarum palustre), rose pogonia (Pogonia ophioglossoides), jack pine (Pinus banksiana), marsh pea (Lathyrus palustris), hair grass (Deschampsia cespitosa), slender bog arrow-grass (Triglochin palustris), panic grass (Dichanthelium lindheimeri), and marsh bellflower (Campanula aparinoides).

The coastal swales often show little zonation, although the larger, deeper swales can have shrubs and herbs along their edges, with emergent bulrushes, spike-rushes, and cat-tails in the shallow water, and submergent and floating plants in the deepest water at the center of the swale. In dry years, the entire wetland may be only moist or dry, in which case many plants from the adjacent beach ridges can establish. Wetlands among parabolic dunes are often drier, supporting a greater percentage of shrubs and sometimes trees. When trees become dominant, the plant community may be classified as Great Lakes barrens, where the swales are located in parabolic dune fields, or as wooded dune and swale complex, where it occurs as a series of parallel swales and low beach ridges.

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Graminoids

- ticklegrass (Agrostis hyemalis)

- blue-joint (Calamagrostis canadensis)

- sedges (Carex aquatilis, C. garberi, C. lasiocarpa, C. stricta, C. viridula, and others)

- twig-rush (Cladium mariscoides)

- tufted hair grass (Deschampsia cespitosa)

- Lindheimer panic grass (Dichanthelium lindheimeri)

- golden-seeded spike-rush (Eleocharis elliptica)

- spike-rush (Eleocharis quinqueflora)

- Baltic rush (Juncus balticus)

- beak-rush (Rhynchospora capillacea)

- hardstem bulrush (Schoenoplectus acutus)

- threesquare (Schoenoplectus pungens)

- false asphodel (Triantha glutinosa)

- common bog arrow-grass (Triglochin maritima)

- slender bog arrow-grass (Triglochin palustris)

Forbs

- purple false foxglove (Agalinis purpurea)

- marsh bellflower (Campanula aparinoides)

- Indian paintbrush (Castilleja coccinea)

- limestone calamint (Clinopodium arkansanum)

- marsh cinquefoil (Comarum palustre)

- common boneset (Eupatorium perfoliatum)

- grass-leaved goldenrod (Euthamia graminifolia)

- small fringed gentian (Gentianopsis virgata)

- geocaulon (Geocaulon lividum)

- Kalm’s lobelia (Lobelia kalmii)

- swamp candles (Lysimachia terrestris)

- balsam ragwort (Packera paupercula)

- grass-of-Parnassus (Parnassia glauca)

- silverweed (Potentilla anserina)

- bird’s-eye primrose (Primula mistassinica)

- Houghton’s goldenrod (Solidago houghtonii)

- Ohio goldenrod (Solidago ohioensis)

- horned bladderwort (Utricularia cornuta)

Fern Allies

- smooth scouring rush (Equisetum laevigatum)

- variegated scouring rush (Equisetum variegatum)

Shrubs

- shrubby cinquefoil (Dasiphora fruticosa)

- Kalm’s St. John’s-wort (Hypericum kalmianum)

- sweet gale (Myrica gale)

- sand dune willow (Salix cordata)

- blue-leaf willow (Salix myricoides)

Trees

- tamarack (Larix laricina)

- jack pine (Pinus banksiana)

- northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis)

Noteworthy Animals

These quickly warming wetlands provide important feeding areas for migrating shorebirds, waterfowl, and songbirds in the spring. They are also important foraging areas for waterfowl in the fall. Spotted sandpipers (Actitis macularia) breed along the margins of interdunal wetlands, and piping plovers (Charadrius melodus) forage at the edges of these wetlands. Great blue herons (Ardea herodias) regularly feed on invertebrates in the swales. Among the invertebrates occupying interdunal wetlands are dragonflies (Suborder Anisoptera), damselflies (Suborder Zygoptera), midges (Family Chionomidae), and probably many others. Leeches (Family Hirundinae) are commonly observed invertebrates in the warm, shallow waters of interdunal swales along Lakes Michigan and Huron.

Rare Plants

- Lycopodiella subappressa (northern appressed clubmoss, state special concern)

- Pinguicula vulgaris (butterwort, state special concern)

- Potamogeton bicupulatus (waterthread pondweed, state threatened)

- Sarracenia purpurea ssp. heterophylla (yellow pitcher-plant, state threatened)

- Solidago houghtonii (Houghton’s goldenrod, federal threatened)

- Tanacetum huronense (Lake Huron tansy, state threatened)

- Utricularia inflata (floating bladderwort, state endangered)

- Utricularia subulata (zigzag bladderwort, state threatened)

Rare Animals

- Acris crepitans blanchardi (Blanchard’s cricket frog, state special concern)

- Ardea herodias (great blue heron, protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918)

- Catinella exile (land snail, state special concern)

- Clemmys guttata (spotted turtle, state threatened)

- Emydoidea blandingii (Blanding’s turtle, state special concern)

- Oncocnemis piffardi (three-striped oncocnemi, state special concern)

- Orchelimum delicatum (delicate meadow katydid, state special concern)

- Papaipema aweme (aweme borer, state special concern)

- Somatochlora hineana (Hine’s emerald, federa/state endangered)

- Vallonia albula (land snail, state special concern)

Biodiversity Management Considerations

Off-road vehicles can damage or destroy the vegetation and habitat of interdunal wetlands, as documented at several sites along the northern Lake Michigan and Lake Huron shorelines. Heavy human usage of the adjacent beach can also threaten associated fauna, such as piping plover and other shorebirds.

Monitoring and control efforts to detect and remove invasive species are critical to the long-term viability of interdunal wetland. Invasive species that may threaten diversity and community structure include reed (Phragmites australis subsp. australis), reed canary grass (Phalaris arundinacea), narrow-leaved cat-tail (Typha angustifolia), hybrid cat-tail (Typha xglauca), purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), spotted knapweed (Centaurea stoebe), baby’s breath (Gypsophila paniculata), common St. John’s-wort (Hypericum perforatum), ox-eye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare), bull thistle (Cirsium vulgare), white sweet clover (Melilotus alba), Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica), hoary alyssum (Berteroa incana), Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis), Canada bluegrass (P. compressa), quack grass (Elymus repens), hawkweeds (Hieracium spp.), sheep sorrel (Rumex acetosella), black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia), white poplar (Populus alba), Lombardy poplar (P. nigra var. italica), common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica), glossy buckthorn (Frangula alnus), autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata), Eurasian honeysuckles (especially Lonicera morrowii, L. tatarica, and L. xbella), and multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora).

Variation

Interdunal wetlands located further inland in dune fields are less subject to water-level fluctuations linked to the Great Lakes, and also much less subject to being filled by moving sand during storms. As a result they often have deeper organic soils, as well as greater dominance by shrubs and occasionally small trees. Unlike the interdunal wetlands of the lower Great Lakes, those along the shores of Lake Superior are not buffered by calcium carbonate; as a result, Lake Superior interdunal wetlands often become acidic and support a flora with more acid-tolerant shrubs and small trees, including leatherleaf (Chamaedaphne calyculata), black chokeberry (Aronia prunifolia), bog rosemary (Andromeda glaucophylla), Labrador tea (Rhododendron groenlandicum), and black spruce (Picea mariana), along with more acid-tolerant sedges, such as boreal bog sedge (Carex magellanica). Sphagnum mosses are a major component in some Lake Superior interdunal wetlands. Interdunal wetlands also form between irregularly formed sand spits, as at Whitefish Point on Lake Superior, where hundreds of small wetlands have formed. The flora of these wetlands share many of the more acid-tolerant shrubs already described for Lake Superior, but no data have been collected on this large wetland complex.

Similar Natural Communities

Coastal fen, limestone cobble shore, northern fen, prairie fen, wooded dune and swale complex, and Great Lakes barrens.

Places to Visit

- Big Knob Campground, Sault Sainte Marie State Forest Management Unit, Mackinac Co.

- Muskegon Dunes, Muskegon State Park, Muskegon Co.

- Nordhouse Dunes, Ludington State Park and Manistee National Forest, Mason Co.

- Sturgeon Bay, Wilderness State Park, Emmett Co.

- Warren Dunes, Warren Dunes State Park, Berrien Co.

Relevant Literature

- Albert, D.A. 2000. Borne of the wind: An introduction to the ecology of Michigan sand dunes. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 63 pp.

- Albert, D.A. 2003. Between land and lake: Michigan’s Great Lakes coastal wetlands. Michigan Natural Features Inventory. Michigan State University Extension, East Lansing, MI. Bulletin E-2902. 96 pp.

- Albert, D.A. 2007. Natural community abstract for interdunal wetland. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 6 pp.

- Comer, P.J., and D.A. Albert. 1993. A survey of wooded dune and swale complexes in Michigan. Michigan Natural Features Inventory report to Michigan Department of Natural Resources, Land and Water Management Division, Coastal Zone Management Program. 159 pp.

- Faber-Langendoen, D., ed. 2001. Plant communities of the Midwest: Classification in an ecological context. Association for Biodiversity Information, Arlington, VA. 61 pp. + appendix (705 pp.).

- Hiebert, R.D., D.A. Wilcox, and N.B. Pavlovic. 1986. Vegetation patterns in and among panes (calcareous intradunal ponds) at the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, Indiana. American Midland Naturalist 116: 276-281.

- Lichtner, J. 1998. Primary succession and forest development on coastal Lake Michigan sand dunes. Ecological Monographs 68: 487-510.

- Soluk, D.A., B.J. Swisher, D.S. Zercher, J.D. Miller, and A.B. Hults. 1998. The ecology of Hine’s emerald dragonfly (Somatochlora hineana): Monitoring populations and determining patterns of habitat use. Activity summary and report of findings (September 1996-August 1997). Illinois Natural History Survey, Champaign, IL. 111 pp.

- Zercher, D. 1999. Hine’s emerald dragonfly (Somatochlora hineana) draft recovery plan. Report to USFWS, Fort Snelling, MN. 110 pp.

For a full list of references used to create this description, please refer to the natural community abstract for Interdunal Wetland.

More Information

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: June 25, 2025).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.