Prairie Fen

Overview

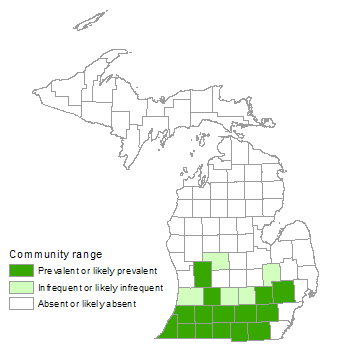

Prairie fen is a wetland community dominated by sedges, grasses, and other graminoids that occurs on moderately alkaline organic soil and marl south of the climatic tension zone in southern Lower Michigan. Prairie fens occur where cold, calcareous, groundwater-fed springs reach the surface. The flow rate and volume of groundwater through a fen strongly influence vegetation patterning; thus, the community typically contains multiple, distinct zones of vegetation, some of which contain prairie grasses and forbs.

Rank

Global Rank: G3 - Vulnerable

State Rank: S3 - Vulnerable

Landscape Context

Prairie fens occur predominantly within poorly drained outwash channels and outwash plains in the interlobate regions of southern Lower Michigan. This area is comprised of coarse-textured end moraines and ice-contact features (eskers and kames) that are bordered by glacial outwash. Prairie fen often occurs where an outwash feature (channel or plain) abuts a coarse-textured end moraine or ice-contact feature.

Historically, the uplands surrounding prairie fens typically supported fire-dependent oak barrens and oak openings. Today, most of the surrounding uplands support closed-canopy oak forest (dry and dry-mesic southern forest), agriculture, or rural residential development.

Prairie fens typically occur as part of large wetland complexes that support a variety of wetland communities including emergent marsh, southern wet meadow, wet prairie, wet-mesic prairie, southern shrub-carr, and rich tamarack swamp. The community is frequently found along both small lakes and the upper reaches of streams and rivers.

Soils

Prairie fen occurs on saturated organic soil and marl, a calcium carbonate (CaCO3) precipitate. Marl deposits can accumulate to depths greater than one meter in lakes and shallow calcareous water as a result of metabolism by algae. The organic soils are typically mildly alkaline, with marl deposits reaching slightly higher levels of alkalinity. The soil profile of prairie fens often contains distinct zones of sedge peat, woody peat, and marl. Thus, the organic deposits may change with depth throughout the soil profile from fibric peat to hemic peat or well-decomposed sapric peat (muck) depending on a fen’s successional history and past disturbance regime. The white- to grayish-colored marl may be present as discrete, sometimes thick, bands within the soil profile or at the surface, where it may occupy small pools surrounding groundwater springs, or cover extensive portions of a fen.

Natural Processes

The groundwater that supports the hydrology of prairie fens is rich in calcium and magnesium carbonates, which are absorbed from the calcareous sand and gravel substrates of the surrounding glacial deposits. Prairie fens occur where cold, calcareous groundwater flows through the community’s organic soil and reaches the surface in the form of perennial springs and seeps. The constant flow of groundwater from springs and seeps can result in the formation of small rivulets that join to form headwater streams, or sheet flows that cover the soil surface with a thin layer of moving water. The substrate around springs and under areas of sheet flow is typically marl, which forms as a result of the metabolic activity of algae growing in water rich in calcium and magnesium carbonates (i.e., hard water). A steady flow of cold, calcareous groundwater also flows beneath the surface through the organic soil of prairie fens. Because the soils remain saturated throughout the year, aerobic bacteria that break down plant materials are much reduced, resulting in the buildup of partially decayed plant debris or peat. The buildup of organic matter around springs and seeps allows some prairie fen complexes to support both areas of “domed fen,” which appear as broad, round hills comprised of organic soils in the middle of the wetland, and “hanging fen,” which occur as low-gradient slopes of organic soil that can span from the upland edge across the wetland to meet level vegetation zones such as sedge meadow or marl flat. Both the domed fen and hanging fen can puzzle observers who are not accustomed to seeing wetlands occurring as hills and sloping terrains. In some locations, the large volume of water underlying prairie fens creates a quaking mat or floating mat, which shakes and reverberates with each step. Quaking mats are especially common where prairie fens occupy former lake basins that have filled with marl or peat. These “basin fens” may occupy the entire basin of an abandoned glacial lake or occupy portions of a basin along the shores of existing lakes.

Historically, fires moving across oak savanna (i.e., oak barrens and oak openings) routinely carried into bordering prairie fens. Most plants found within prairie fens are well adapted to fire. By consuming dried leaves from the previous growing season, fire increases the availability of important plant nutrients and reduces the thickness of the duff layer. The resulting reduction in litter allows light to reach the soil surface where it stimulates seed germination. Fire also facilitates seedling establishment by reducing competition from robust perennials, especially during the early growing season. The increased nutrient availability contributes to enhanced growth and bolsters flowering and seed set. By killing or top-killing shrubs and trees, fires help maintain the open and semi-open structure on which many of the community’s plants and animals depend. In summary, fire is an important ecological process for prairie fen as it facilitates nutrient cycling, seed bank expression and maintenance, and helps maintain community structure.

Historically, flooding resulting from beaver dams was very likely a common occurrence in the level and lower-elevation portions of prairie fen complexes. Prolonged flooding can kill trees, shrubs, and many herbaceous plants and results in conversion of prairie fen to shallow ponds, emergent marsh, or southern wet meadow.

Vegetation

Prairie fens typically contain several distinct vegetation zones, which may include inundated flat, sedge meadow, marl flat, and wooded fen. The vegetation zones correspond to differing levels of groundwater influence, water chemistry, organic or marl accumulation, and past natural and anthropogenic disturbances. Not all vegetation zones occur in all prairies fens.

Inundated flat can occur in low, level areas and near the margins of streams and lakes. Dominant species in this zone include hardstem bulrush (Schoenoplectus acutus), three-square (S. pungens), lake sedge (Carex lacustris), water sedge (C. aquatilis), broad-leaved cat-tail (Typha latifolia), and common arrowhead (Sagittaria latifolia).

Sedge meadow is typically the largest vegetative zone of a prairie fen and is dominated by sedges, grasses, forbs, and low shrubs. The sedge meadow zone may occur in low, level areas and on slopes as hanging fen or domed fen, where it often assumes a shorter stature overall. Characteristic sedges include tussock sedge (Carex stricta), dioecious sedge (C. sterilis), wiregrass sedge (C. lasiocarpa), Bauxbaum's sedge (C. buxbaumii), prairie sedge (C. prairea), and lesser panicled sedge (C. diandra). Common grasses include big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), Indian grass (Sorghastrum nutans), marsh wild-timothy (Muhlenbergia glomerata), fringed brome (Bromus ciliatus), bluejoint grass (Calamagrostis canadensis), and slender wheat grass (Elymus trachycaulus). Common forbs and ferns include tall flat-top white aster (Doellingeria umbellata), common boneset (Eupatorium perfoliatum), joe-pye-weed (Eutrochium maculatum), whorled loosestrife (Lysimachia quadriflora), sensitive fern (Onoclea sensibilis), Virginia mountain mint (Pycnanthemum virginianum), black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta), Ohio goldenrod (Solidago ohioensis), Riddell’s goldenrod (S. riddellii), bog goldenrod (S. uliginosa), smooth swamp aster (Symphyotrichum firmum), side-flowering aster (S. lateriflorum), swamp aster (S. puniceum), and marsh fern (Thelypteris palustris). Low shrubs occurring within the sedge meadow zone include shrubby cinquefoil (Dasiphora fruticosa), alder-leaved buckthorn (Rhamnus alnifolia), sage willow (Salix candida), meadowsweet (Spiraea alba), and bog birch (Betula pumila). Scattered tall shrubs and trees may also occur, especially poison sumac (Toxicodendron vernix) and tamarack (Larix laricina).

Marl flats are distinct features of fens, forming in areas of calcareous groundwater seepage. They may occur as small pools or extensive, level areas occupying the basins of former lakes. In the latter, low peat ridges that support sphagnum mosses (Sphagnum spp.), pitcher-plant (Sarracenia purpurea), and stunted tamarack may be interspersed throughout the broad flats. Because the alkaline conditions permit few species to survive, marl flats are sparsely vegetated. Species occurring within marl flats include sedges (Carex flava, C. leptalea, and C. sterilis), Kalm’s lobelia (Lobelia kalmii), grass-of-Parnassus (Parnassia glauca), beak-rushes (Rhynchospora alba and R. capillacea), common bog arrow-grass (Triglochin maritima), twig-rush (Cladium mariscoides), rush (Juncus brachycephalus), golden-seeded spike-rush (Eleocharis elliptica), beaked spike-rush (Eleocharis rostellata), white lady’s-slipper (Cypripedium candidum, state threatened), white camas (Anticlea elegans), and carnivorous plants such as round-leaved sundew (Drosera rotundifolia), pitcher-plant, flat-leaved bladderwort (Utricularia intermedia), and horned bladderwort (U. cornuta).

The wooded fen zone represents portions of the fen that are slowly succeeding to closed-canopy communities such as southern shrub-carr and rich tamarack swamp in the absence of management or natural disturbance. Many of the herbaceous species from the other vegetation zones also occur within wooded fen. Woody species occurring in this zone include poison sumac, bog birch, tamarack, silky dogwood (Cornus amomum), gray dogwood (C. foemina), red-osier dogwood (C. sericea), winterberry (Ilex verticillata), ninebark (Physocarpus opulifolius), nannyberry (Viburnum lentago), yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis), red maple (Acer rubrum), and American elm (Ulmus americana). The wooded fen zone in most of the remaining prairie fens occupies a significantly greater area today than in the past due to the absence of fire and beaver flooding.

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Graminoids

- big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii)

- fringed brome (Bromus ciliatus)

- blue-joint (Calamagrostis canadensis)

- sedges (Carex aquatilis, C. buxbaumii, C. cryptolepis, C. diandra, C. flava, C. interior, C. lasiocarpa, C. leptalea, C. meadii, C. prairea, C. sterilis, C. stricta, C. tetanica, C. viridistellata, and others)

- twig-rush (Cladium mariscoides)

- spike-rushes (Eleocharis elliptica, E. rostellata, and others)

- slender wheat grass (Elymus trachycaulus)

- sweet grass (Hierochloe hirta)

- rush (Juncus brachycephalus)

- marsh wild-timothy (Muhlenbergia glomerata)

- beak-rushes (Rhynchospora alba and R. capillacea)

- little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium)

- hardstem bulrush (Schoenoplectus acutus)

- threesquare (Schoenoplectus pungens)

- nut-rush (Scleria verticillata)

- Indian grass (Sorghastrum nutans)

Forbs

- swamp agrimony (Agrimonia parviflora)

- white camas (Anticlea elegans)

- tuberous Indian plantain (Arnoglossum plantagineum)

- swamp thistle (Cirsium muticum)

- white lady-slipper (Cypripedium candidum)

- showy lady-slipper (Cypripedium reginae)

- flat-topped white aster (Doellingeria umbellata)

- round-leaved sundew (Drosera rotundifolia)

- common boneset (Eupatorium perfoliatum)

- joe-pye-weed (Eutrochium maculatum)

- small fringed gentian (Gentianopsis virgata)

- marsh blazing-star (Liatris spicata)

- Kalm’s lobelia (Lobelia kalmii)

- whorled loosestrife (Lysimachia quadriflora)

- grass-of-Parnassus (Parnassia glauca)

- swamp-betony (Pedicularis lanceolata)

- glaucous white lettuce (Prenanthes racemosa)

- common mountain mint (Pycnanthemum virginianum)

- black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta)

- pitcher-plant (Sarracenia purpurea)

- rosin weed (Silphium integrifolium)

- goldenrods (Solidago ohioensis, S. riddellii, S. uliginosa, and others)

- nodding ladies’-tresses (Spiranthes cernua)

- asters (Symphyotrichum boreale, S. firmum, S. lateriflorum, and others)

- false asphodel (Triantha glutinosa)

- common bog arrow-grass (Triglochin maritima)

- bladderwort (Utricularia cornuta and U. intermedia)

- bog valerian (Valeriana uliginosa)

- golden alexanders (Zizia aurea)

Ferns

- sensitive fern (Onoclea sensibilis)

- marsh fern (Thelypteris palustris)

Fern Allies

- selaginella (Selaginella eclipes)

Mosses

- brown mosses (Family Amblystegiaceae)

- star campylium moss (Campylium stellatum)

- scorpidium moss (Scorpidium scorpioides)

- sphagnum mosses (Sphagnum spp.)

Shrubs

- bog birch (Betula pumila)

- dogwoods (Cornus spp.)

- shrubby cinquefoil (Dasiphora fruticosa)

- ninebark (Physocarpus opulifolius)

- alder-leaved buckthorn (Rhamnus alnifolia)

- willows (Salix bebbiana, S. candida, S. discolor, S. lucida, S. petiolaris, and others)

- meadowsweet (Spiraea alba)

- poison sumac (Toxicodendron vernix)

Trees

- red maple (Acer rubrum)

- red-cedar (Juniperus virginiana)

- tamarack (Larix laricina)

- American elm (Ulmus americana)

Noteworthy Animals

Ant mounds reaching more than half a meter in height and one meter in width are a common feature within the sedge meadow zone and where woody species have recently colonized open fen.

Rare Plants

- Asclepias purpurascens (purple milkweed, state special concern)

- Aster praealtus (willow aster, state special concern)

- Berula erecta (cut-leaved water-parsnip, state threatened)

- Cacalia plantaginea (prairie Indian-plantain, state special concern)

- Calamagrostis stricta (narrow-leaved reedgrass, state threatened)

- Carex richardsonii (Richardson’s sedge, state threatened)

- Cypripedium candidum (white lady’s-slipper, state threatened)

- Dodecatheon meadia (shooting-star, state endangered)

- Drosera anglica (English sundew, state threatened)

- Eryngium yuccifolium (rattlesnake-master, state threatened)

- Filipendula rubra (queen-of-the-prairie, state threatened)

- Helianthus hirsutus (whiskered sunflower, state special concern)

- Muhlenbergia richardsonis (mat muhly, state threatened)

- Phlox maculata (wild sweet william, state threatened)

- Polemonium reptans (Jacob’s ladder, state threatened)

- Pycnanthemum muticum (broad-leaved mountain mint, state threatened)

- Sanguisorba canadensis (Canadian burnet, state threatened)

- Sporobolus heterolepis (prairie dropseed, state special concern)

- Valeriana edulis var. ciliata (edible valerian, state threatened)

Rare Animals

- Acris crepitans blanchardi (Blanchard’s cricket frog, state special concern)

- Calephelis muticum (swamp metalmark, state special concern)

- Clemmys guttata (spotted turtle, state threatened)

- Clonophis kirtlandii (Kirtland’s snake, state endangered)

- Dorydiella kansana (leafhopper, state special concern)

- Emydoidea blandingii (Blanding’s turtle, state special concern)

- Flexamia huroni (Huron River leafhopper, state special concern)

- Lepyronia angulifera (angular spittlebug, state special concern)

- Neonympha m. mitchellii (Mitchell's satyr, federal/state endangered)

- Oarisma poweshiek (Poweshiek skipper, state threatened)

- Oecanthus laricis (tamarack tree cricket, state special concern)

- Papaipema beeriana (blazing star borer, state special concern)

- Papaipema sciata (Culver’s root borer, state special concern)

- Papaipema silphii (silphium borer moth, state threatened)

- Papaipema speciosissima (regal fern borer, state special concern)

- Prosapia ignipectus (red-legged spittlebug, state special concern)

- Sistrurus c. catenatus (eastern massasauga, federal candidate species and state threatened)

- Terrapene c. carolina (eastern box turtle, state special concern)

Biodiversity Management Considerations

Land use planning to protect groundwater reserves in areas surrounding prairie fens is critical to maintaining the natural community. Drainage ditches can interrupt groundwater flow through fens, reducing water levels and facilitating rapid establishment and growth of shrubs and trees. Nutrient additions from leaking septic tanks, drain fields, or agricultural runoff can contribute to dominance by invasive species such as reed (Phragmites australis subsp. australis), reed canary grass (Phalaris arundinacea), and narrow-leaved cat-tail (Typha angustifolia).

Today, most prairie fens are significantly reduced in size as a result of shrub and tree establishment. In addition, the surrounding uplands have also changed from open, oak savanna or woodland, to closed-canopy forest. Historically, the principal natural process that maintained the open structure of these upland and wetland communities was fire. Thus, reintroducing fire through prescription burning of prairie fens and adjacent upland oak forests is a critical management need. Because of the small and fragmented condition of many of our remaining prairie fens, use of prescribed fire as a management tool should include setting aside significant portions of fen to remain unburned in any given year to help lessen impacts to fire-sensitive species. Streams, rivers, lakes, and wet lines created by hoses can serve as fire breaks for establishing unburned refugia within a prairie fen.

In addition to prescribed fire, reducing the density of trees and shrubs also typically requires the use of herbicides, which can be applied to the recently cut stumps of woody plants. Cutting woody plants without applying herbicides is typically ineffective at reducing shrub and tree density because the plants resprout and grow rapidly from well developed root stocks.

Invasive species that reduce diversity and alter community structure in prairie fen include reed, reed canary grass, narrow-leaved cat-tail, hybrid cat-tail (Typha xglauca), purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), glossy buckthorn (Frangula alnus), common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica), multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora), and autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata). Glossy buckthorn, an invasive shrub, has become especially widespread and well established in prairie fens, where it has formed dense monocultures, replacing formerly species-rich open fen. Invasive species can spread rapidly and outcompete native plants for nutrients, light, and space. Reducing well established populations of invasive plants typically requires long-term commitments by managers to repeatedly apply control treatments, over multiple years, and carryout sustained monitoring efforts. The use of herbicides in controlling invasive species can be very effective, while cultural treatments such as pulling, mowing, and cutting by themselves generally have poor results.

Variation

Because of their proximity to the range of prairie in North America, prairie fens occurring in far southwestern Lower Michigan generally have a greater abundance and diversity of species associated with prairies than those located farther north and east.

Prairie fens can differ significantly in appearance from one another based on amount of groundwater input and water chemistry, disturbance history, proximity to streams or lakes, and position related to local landforms (outwash channels, moraines, etc.). Fens with extensive marl flats often develop on former glacial lakebeds (i.e., basin fens) and contain low, acidic peat mounds that support species associated with bogs. Domed fens occur where the buildup of organic soils around groundwater discharge areas has resulted in the creation of a large, low broad hill within the wetland. The broad peat domes usually support low vegetation associated with the sedge meadow zone. Hanging fens are often associated with the edges of moraines, eskers, and kames and appear as low gradient slopes along the edges of the upland. Hanging fens typically slope from the edges of the upland to level marl flats or stream channels and support low vegetation associated with the sedge meadow zone. Quaking mats are common features of prairie fens and are typically associated with springs, the edges of lakes, or basins of former glacial lakes that have filled with peat (i.e., basin fens). Quaking mats form as fen sedges creep out into open water or emergent or submergent marshes along the edges of lakes. Vegetation is typically low and dominated by sedges.

Similar Natural Communities

Northern fen, southern wet meadow, emergent marsh, coastal fen, poor fen, southern shrub-carr, wet prairie, wet-mesic prairie, and rich tamarack swamp.

Places to Visit

- Algoe Lake Fen, Ortonville State Recreation Area, Lapeer Co.

- Brandt Road Fen and Halstead Lake, Holly State Recreation Area, Oakland Co.

- Hill Creek Fen (Great Fen) and Shaw Lake Fen, Barry State Game Area, Barry Co.

- Ives Road Fen Preserve, The Nature Conservancy, Lenawee Co.

- Little Goose Lake Fen, Michigan Nature Association (Goose Creek Grasslands Nature

- Sanctuary), Lenawee Co.

- Long Lake Fen, Springfield Township (Shiawassee Basin Preserve), Oakland Co.

- Marsh Brook Fen, Watkins Lake State Park, Jackson Co.

- Park Lyndon Fen, Pinckney State Recreation Area and Washtenaw County Park,

- Washtenaw Co.

- Paw Paw Prairie Fen Preserve, The Nature Conservancy, Van Buren Co.

Relevant Literature

- Almendinger, J.E., and J.H. Leete. 1998. Regional and local hydrogeology of calcareous fens in the Minnesota River basin, USA. Wetlands 18(2): 184-202.

- Amon, J.P., C.A. Thompson, Q.J. Carpenter, and J. Miner. 2002. Temperate zone fens of the glaciated Midwestern USA. Wetlands 22(2): 301-317.

- Bedford, B.L., and K.S. Godwin. 2003. Fens of the United States: Distribution, characteristics, and scientific connection versus legal isolation. Wetlands 23(3): 608-629.

- Bowles, M.L., J.L. McBride, N. Stoynoff, and K. Johnson. 1996. Temporal change in vegetation structure in a fire-managed prairie fen. Natural Areas Journal 16(4): 275-288.

- Bowles, M.L., P.D. Kelsey, and J.L. McBride. 2005. Relationships among environmental factors, vegetation zones, and species richness in a North American calcareous prairie fen. Wetlands 25(3): 685-696.

- Miner, J.J., and D.B. Ketterling. 2003. Dynamics of peat accumulation and marl flat formation in calcareous fen, Midwestern United States. Wetlands 23(4): 950-960.

- Moran, R.C. 1981. Prairie fens in northeastern Illinois: Floristic composition and disturbance. In Proceedings of the Sixth North American Prairie Conference, ed. R.L. Stuckey and K.J. Reese. Ohio Biological Survey Notes 15. Ohio State University, Columbus, OH. 278 pp.

- Spieles, J.B., P.J. Comer, D.A. Albert, and M.A. Kost. 1999. Natural community abstract for prairie fen. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 4 pp.

- White, M.A., and K.A. Chapman. 1988. Element stewardship abstract for alkaline shrub/herb fen, lower Great Lakes type. Midwest Heritage Task Force, The Nature Conservancy. 14 pp.

For a full list of references used to create this description, please refer to the natural community abstract for Prairie Fen.

More Information

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: February 20, 2026).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.