Northern Hardwood Swamp

Overview

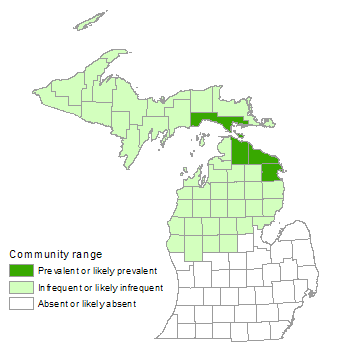

Northern hardwood swamp is a seasonally inundated, deciduous swamp forest community dominated by black ash (Fraxinus nigra) that occurs on neutral to slightly acidic, hydric mineral soils and shallow muck over mineral soils. Located north of the climatic tension zone, northern hardwood swamp is found primarily in depressions on level to hummocky glacial lakeplains, fine- and medium-textured glacial tills, and broad flat outwash plains. Fundamental disturbance factors affecting northern hardwood swamp development include seasonal flooding and windthrow.

Rank

Global Rank: G4 - Apparently secure

State Rank: S3 - Vulnerable

Landscape Context

Northern hardwood swamps can be found in diverse landscape settings, including abandoned lakebeds, level to hummocky glacial lakeplains, shallow basins, groundwater seeps, low, level terrain near rivers, lakes, or wetlands, and small depressions around edges of peatlands. The majority of circa 1800 black ash swamps were located on flat lacustrine plains, fine- and medium-textured glacial tills, or broad flat outwash plains. Northern hardwood swamps occur on poorly drained soils and in areas that receive seasonal flooding or have high water tables. Perched saturated pockets and pools of standing water are common features of northern hardwood swamp, especially during spring. Because they occupy depressions, these ecosystems are colder than the immediately surrounding landscape.

Soils

Soils are poorly to very poorly drained and often consist of a shallow layer of muck (i.e., sapric peat) overlaying mineral soil. The texture of mineral soils is most commonly fine sandy clay loam to fine loam and an underlying impermeable clay lens is often present.

Natural Processes

Seasonal flooding is the primary disturbance in northern hardwood swamps. Standing water, usually a result of groundwater seepages, can reach over 30 cm (12 in) in depth, and is usually present in spring and drained by late summer. Water often pools due to an impermeable clay layer in the soil profile. Overstory species associated with flooding have several adaptations to soil saturation such as hypertrophied lenticels (oversized pores on woody stems that foster gas exchange between plants and the atmosphere), rapid stomatal closure, adventitious roots, and reproductive plasticity. Flooding extent has even been found to dictate the mode of regeneration for black ash. For example, heavy flooding events usually result in vegetative reproduction by stump sprouting, whereas less prolonged flooding fosters sexual reproduction.

Differences in species composition, in particular the distribution of different species of ash, are dependent upon variation in timing, extent, and duration of high water. The relationship between variations in flooding and species composition is demonstrated by the differences between black ash-dominated swamps, and river floodplains where green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica) is a more common dominant species. Green ash requires moving, oxygen-rich water characteristic of river floodplains, whereas black ash has adapted to the usually stagnant water with reduced oxygen content associated with swamp depressions. Green ash on river floodplains withstands routine flooding throughout the growing season. Black ash is very tolerant of low oxygen levels found in stagnant swamps, but is intolerant of flooding well into the growing season. Massive dieback of understory and sometimes overstory trees results from extended periods of high water in northern hardwood swamps. An adaptation to this common occurrence is the long dormancy period (up to eight years) of black ash seeds. In northern hardwood swamps, drier periods that allow for exposure of saturated organic soils are essential for regeneration of swamp vegetation. However, because of the high water-retaining capacity of sapric peat, soil moisture within northern hardwood swamp is typically maintained throughout the growing season, unlike the mineral soils of many floodplains, which can experience summer droughts. While xeric stress is harmful to shallow rooting black ash seedlings, green ash commonly withstands periods of low soil moisture on river floodplains. Black ash-dominated northern hardwood swamp communities are therefore restricted to depressions, or low, level terrain near rivers, lakes, or wetlands that experience seasonal flooding but not the more pronounced levels of soil desiccation found in floodplain systems.

Historically, catastrophic disturbances in northern hardwood swamp other than flooding were most likely infrequent. Large-scale windthrow and fire in northern hardwood swamps of Minnesota had a rotation of 370 and 1000 years, respectively. However, small windthrow events are common in these systems due to shallow rooting within muck soils. The uprooting of trees creates pit and mound microtopography that results in fine-scale gradients of soil moisture and soil chemistry. Microtopography is an important driver of vegetation patterns within swamp systems since it provides a diversity of microsites for plant establishment. As floodwater drains, both the residual mucky pools and exposed mounds left by uprooted trees provide unique substrates for a variety of northern hardwood swamp plants. Coarse woody debris, which typically lies above the zone of flooding, remains a continued source of saturated substrate for seed germination and seedling establishment through drier periods.

A common agent in hydrologic change in northern hardwood swamps is beaver. Through dam-building activities, beaver can initiate substantial hydrologic change, either causing prolonged flooding or lowering of the water table depending on the location of the swamp in relation to the dam. Behind a beaver dam the water table is higher, while below it drier conditions are generated. In addition to altering hydrology, beaver can generate canopy gaps within these systems by cutting down trees. Through flooding and herbivory, beaver can cause tree mortality and the conversion of northern hardwood swamp to open wetlands such as northern shrub thicket or northern wet meadow.

Vegetation

Black ash (Fraxinus nigra) is the overwhelming canopy dominant of northern hardwood swamp communities. Canopy associates of black ash include red maple (Acer rubrum), silver maple (A. saccharinum), American elm (Ulmus americana), yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis), basswood (Tilia americana), balsam fir (Abies balsamea), northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis), and green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica). However, these species are all found in greater density in other communities. The shrub layer can consist of saplings of overstory species along with winterberry (Ilex verticillata) and tag alder (Alnus incana). Northern hardwood swamps are characterized by a diverse ground flora that is patchy both seasonally and spatially depending on timing, location, and duration of flooding. Sites are often saturated to inundated in spring and following heavy rains, resulting in numerous sparsely vegetated to bare areas in the understory and ground layers. During the late growing season, when seasonal waters draw down, the herbaceous layer is typically dense.

Common herbaceous plants include northern bugleweed (Lycopus uniflorus), mad-dog skullcap (Scutellaria lateriflora), wood anemone (Anemone quinquefolia), jack-in-the-pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum), false nettle (Boehmeria cylindrica), marsh marigold (Caltha palustris), Pennsylvania bitter cress (Cardamine pensylvanica), fringed sedge (Carex crinita), great bladder sedge (C. intumescens), small enchanter’s nightshade (Circaea alpina), goldthread (Coptis trifolia), fragrant bedstraw (Galium triflorum), fowl manna grass (Glyceria striata), jewelweed (Impatiens capensis), wild iris (Iris versicolor), wood nettle (Laportea canadensis), Canada mayflower (Maianthemum canadense), wild mint (Mentha canadensis), partridge berry (Mitchella repens), naked miterwort (Mitella nuda), Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia), clearweed (Pilea pumila), elliptic shinleaf (Pyrola elliptica), dwarf raspberry (Rubus pubescens), water parsnip (Sium suave), skunk cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus), and wild violets (Viola spp.). Common ferns include sensitive fern (Onoclea sensibilis), cinnamon fern (Osmunda cinnamomea), royal fern (O. regalis), ostrich fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris), and oak fern (Gymnocarpium dryopteris). In addition, horsetails (Equisetum spp.) are also prevalent in northern hardwood swamps.

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Graminoids

- sedges (Carex crinita, C. intumescens, C. lupulina, and others)

- wood reedgrasses (Cinna arundinacea and C. latifolia)

- Virginia wild-rye (Elymus virginicus)

- fowl manna grass (Glyceria striata)

- rice cut grass (Leersia oryzoides)

- fowl meadow grass (Poa palustris)

Forbs

- jack-in-the-pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum)

- false nettle (Boehmeria cylindrica)

- marsh-marigold (Caltha palustris)

- Pennsylvania bitter cress (Cardamine pensylvanica)

- turtlehead (Chelone glabra)

- small enchanter’s-nightshade (Circaea alpina)

- goldthread (Coptis trifolia)

- flat-topped white aster (Doellingeria umbellata)

- willow-herbs (Epilobium spp.)

- fragrant bedstraw (Galium triflorum)

- jewelweed (Impatiens capensis)

- wild blue flag (Iris versicolor)

- wood nettle (Laportea canadensis)

- northern bugle weed (Lycopus uniflorus)

- tufted loosestrife (Lysimachia thyrsiflora)

- Canada mayflower (Maianthemum canadense)

- partridge berry (Mitchella repens)

- naked miterwort (Mitella nuda)

- smartweeds (Persicaria spp.)

- clearweed (Pilea pumila)

- mad-dog skullcap (Scutellaria lateriflora)

- water parsnip (Sium suave)

- goldenrods (Solidago patula, S. rugosa, and others)

- calico aster (Symphyotrichum lateriflorum)

- swamp aster (Symphyotrichum puniceum)

- skunk-cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus)

Ferns

- oak fern (Gymnocarpium dryopteris)

- ostrich fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris)

- sensitive fern (Onoclea sensibilis)

- cinnamon fern (Osmunda cinnamomea)

- royal fern (Osmunda regalis)

Fern Allies

- horsetails (Equisetum spp.)

Woody Vines

- Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia)

Shrubs

- tag alder (Alnus incana)

- winterberry (Ilex verticillata)

- dwarf raspberry (Rubus pubescens)

Trees

- balsam fir (Abies balsamea)

- red maple (Acer rubrum)

- silver maple (Acer saccharinum)

- yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis)

- black ash (Fraxinus nigra)

- green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica)

- northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis)

- basswood (Tilia americana)

- American elm (Ulmus americana)

Noteworthy Animals

Black ash seeds are an important food source for game birds, songbirds, and small mammals, and the leaves provide browse for deer and moose. Beaver can cause prolonged flooding, which results in widespread mortality of black ash and other species not adapted to such conditions.

Rare Plants

- Carex assiniboinensis (Assiniboia sedge, state threatened)

- Gentiana linearis (narrow-leaved gentian, state threatened)

- Poa paludigena (bog bluegrass, state threatened)

Rare Animals

- Accipiter cooperii (Cooper’s hawk, state special concern)

- Accipiter gentiles (northern goshawk, state special concern)

- Alces alces (moose, state special concern)

- Appalachiana sayanus (spike-lip crater, state special concern)

- Ardea herodias (great blue heron, protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918)

- Canis lupus (gray wolf, federal/state threatened)

- Emydoidea blandingii (Blanding’s turtle, state special concern)

- Felis concolor (cougar, state endangered)

- Haliaeetus leucocephalus (bald eagle, state threatened)

- Pachypolia atricornis (three-horned moth, state special concern)

- Pandion haliaetus (osprey, state threatened)

- Sistrurus c. catenatus (eastern massasauga, federal candidate species and state special concern)

- Terrapene c. carolina (eastern box turtle, state special concern)

Biodiversity Management Considerations

Where the primary conservation objective is to maintain biodiversity in northern hardwood swamps, the best management practice is to leave large tracts unharvested and allow natural processes (e.g., flooding, windthrow, and senescence) to operate unhindered. Black ash is a slow growing species and is usually found with small diameters, under 25 cm DBH (10 in), and is therefore of minor commercial value. Black ash is, however, a component of northern Wisconsin and Upper Peninsula Michigan sawtimber production. Clear-cutting black ash swamps can cause the loss of the community type due to the rises in the water table resulting from decreased transpiration following tree removal.

Threats to northern hardwood swamps involve hydrological impacts such as drainage for agriculture, sedimentation due to logging or construction, or the deleterious impacts of stormwater or wastewater runoff either causing prolonged flooding outside the natural range of variation, or significantly increasing nutrient levels and facilitating establishment of invasive species. Invasive species that may threaten the diversity and community structure of northern hardwood swamp include glossy buckthorn (Frangula alnus), purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), narrow-leaved cat-tail (Typha angustifolia), hybrid cat-tail (Typha xglauca), reed (Phragmites australis subsp. australis), reed canary grass (Phalaris arundinacea), and European marsh thistle (Cirsium palustre). Regular monitoring for these and other invasive species followed by prompt and sustained control efforts will help protect the ecological integrity of northern hardwood swamp and adjacent natural communities.

In southern Lower Michigan, the introduction of the emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis) has initiated new concern for ecosystems in which ash plays a significant role. The emerald ash borer (EAB), established in southeastern Lower Michigan around 1990, infests and kills all species of ash. Like Dutch elm disease, which has virtually eliminated American elm as a dominant overstory tree of swamp communites, EAB is having a similar effect on southern hardwood swamps and floodplain forests dominated by black or green ash. Outside the main area of infestation in southeastern Michigan, the density and health of ash is relatively robust, which will likely foster the expansion EAB throughout Michigan and into adjacent states and provinces.

Variation

Northern hardwood swamps occurring on lakeplains tend to be larger than those found in kettle depressions, which are limited in area by the size of the glacial ice-block that formed the basin.

Similar Natural Communities

Southern hardwood swamp, hardwood-conifer swamp, northern shrub thicket, and floodplain forest.

Places to Visit

- Bear Swamp, Manistee National Forest, Lake Co. and Mason Co.

- Hopper's Swamp, Manistee National Forest, Manistee Co. and Mason Co.

- Porcupine Mountains, Porcupine Mountains Wilderness State Park, Gogebic Co. and Ontonagon Co.

- Walloon Lake Swamp, Gaylord State Forest Management Unit, Charlevoix Co.

Relevant Literature

- Erdmann, G.G., T.R. Crow, R.M. Peterson, Jr., and C.D. Wilson. 1987. Managing black ash in the Lake States. USDA, Forest Service, North Central Forest Experiment Station, Technical Report NC-115.

- Faber-Langendoen, D., ed. 2001. Plant communities of the Midwest: Classification in an ecological context. Association for Biodiversity Information, Arlington, VA. 61 pp. + appendix (705 pp.).

- MacFarlane, D.W., and S.P. Meyer. 2005. Characteristics and distribution of potential ash tree hosts for emerald ash borer. Forest Ecology and Management 213: 15-24.

- McCullough, D.G., and D.L. Roberts. 2002. Emerald ash borer. USDA, Forest Service, Northeast Area, State and Private Forests, Pest Alert NA-PR-07-02.

- Tardif, J., S. Dery, and Y. Bergeron. 1994. Sexual regeneration of black ash (Fraxinus nigra Marsh.) in a boreal floodplain. American Midland Naturalist 132(1): 124-135.

- Tardif, J., and Y. Bergeron. 1999. Population dynamics of Fraxinus nigra in response to flood-level variation in Northwestern Quebec. Ecological Monographs 69(1): 107-125.

- Weber, C.R, J.G. Cohen, and M.A. Kost. 2007. Natural community abstract for northern hardwood swamp. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 8 pp.

- Wright, J.W., and H.M. Rauscher. 1990. Black ash. Pp. 344-347 in Silvics of North America Volume 2, Hardwoods, ed. R.M. Burns and B.G. Honkala. Agricultural Handbook 654. USDA, Washington D.C. 877 pp.

For a full list of references used to create this description, please refer to the natural community abstract for Northern Hardwood Swamp.

More Information

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: August 24, 2025).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.