Sinkhole

Overview

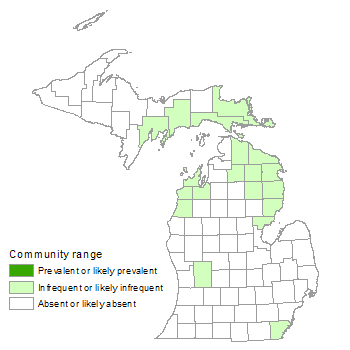

Sinkholes are depressions in the landscape caused by the dissolution and collapse of subsurface limestone, dolomite, or gypsum. The term karst, first applied to a plateau region of the Dinaric Alps in Yugoslavia, is now used to describe regions throughout the world that have features formed largely by underground drainage. Karst terrains are characterized by caves, steep valleys, sinkholes, and a general lack of surface streams. Sinkholes are found predominantly in the northeastern Lower Peninsula and eastern Upper Peninsula.

Rank

Global Rank: G3G5

State Rank: S2 - Imperiled

Landscape Context

Michigan’s areas of true karst are limited in extent, but include considerable variety. The most extensive area of sinkholes and earth cracks is found in Alpena and Presque Isle Counties. A broad band of outcrops of the Niagara Escarpment in the Upper Peninsula contains numerous karst sinks, springs, and caves. Gypsum karst is found in Kent and Iosco Counties; a significant amount of surface drainage goes underground in Monroe County, reappearing as "blue holes" in Lake Erie. In addition, numerous sinkhole lakes occur within Otsego and Montmorency Counties. The surrounding landscape typically supports mesic northern forest, boreal forest, limestone bedrock glade, and alvar in the uplands and groundwater-fed wetland systems such as northern fen, poor fen, intermittent wetland, and rich conifer swamp in the lowlands. Where deep outwash sands overlay sinkholes, drier upland types may occur including dry-mesic northern forest and dry northern forest.

Soils

The soils within most of Michigan’s karst features are derived from limestone or dolomite, and are thus mildly to moderately alkaline and fine-textured. Some of the sinkholes in Montmorency, Otsego, and Presque Isle Counties are overlain by outwash sands and support vegetation characteristic of acid sands — no bedrock is exposed in these sinkholes.

Natural Processes

Karst forms a dynamic, ever-changing landscape resulting from the dissolution of limestone, dolomite, or gypsum. The dissolution of the bedrock, often along faults or cracks in the bedrock, results in the creation of an underground drainage system rather than typical surface streams. As the dissolution of the underlying bedrock continues, it collapses in some locations and forms sinkholes, some of which seasonally or permanently flood to form lakes or ponds. Some underground streams of the karst regions reemerge as springs, sometimes off shore in Lake Michigan or Lake Huron. Coarse woody debris loads from surrounding uplands provide important structural features within sinkholes. Recently formed sinkholes are often covered by fallen logs.

Vegetation

Although the vegetation is predominantly that of the surrounding forest, moister and cooler conditions may provide habitat for ferns, mosses, and lichens not typically found in the area of the sinkhole. Vertical limestone walls are often exposed along the margins of sinkholes and provide habitat for species characteristic of limestone cliffs. Where exposures of limestone are prevalent, sinkholes support a diversity of mosses, lichens, liverworts, and ferns. Where sinkhole ponds or lakes develop, emergent marsh often rings the shore of the water. However, the flora of Michigan’s karst is much less diverse than karst floras in the southeastern U.S., where rare plant diversity is often high.

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Graminoids

- big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii)

- blue-joint (Calamagrostis canadensis)

- sedges (Carex aurea, C. eburnea, C. flava, C. pensylvanica, C. viridula, and others)

- twig-rush (Cladium mariscoides)

- poverty grass (Danthonia spicata)

- common spike-rush (Eleocharis palustris)

- fowl manna grass (Glyceria striata)

- Canadian rush (Juncus canadensis)

- little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium)

- hardstem bulrush (Schoenoplectus acutus)

- green bulrush (Scirpus atrovirens)

- cordgrass (Spartina pectinata)

Forbs

- wild sarsaparilla (Aralia nudicaulis)

- jack-in-the-pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum)

- wormwood (Artemisia campestris)

- harebell (Campanula rotundifolia)

- marsh cinquefoil (Comarum palustre)

- large-leaved aster (Eurybia macrophylla)

- wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana)

- wild blue flag (Iris versicolor)

- cardinal flower (Lobelia cardinalis)

- Kalm’s lobelia (Lobelia kalmii)

- common water horehound (Lycopus americanus)

- northern bugle weed (Lycopus uniflorus)

- Canada mayflower (Maianthemum canadense)

- false spikenard (Maianthemum racemosum)

- water smartweed (Persicaria amphibia)

- downy Solomon seal (Polygonatum pubescens)

- mad-dog skullcap (Scutellaria lateriflora)

Ferns

- lady fern (Athyrium filix-femina)

- rattlesnake fern (Botrypus virginianus)

- bulblet fern (Cystopteris bulbifera)

- oak fern (Gymnocarpium dryopteris)

- sensitive fern (Onoclea sensibilis)

- royal fern (Osmunda regalis)

- bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum)

- marsh fern (Thelypteris palustris)

Woody Vines

- poison-ivy (Toxicodendron radicans)

Shrubs

- bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi)

- sweetfern (Comptonia peregrina)

- bunchberry (Cornus canadensis)

- gray dogwood (Cornus foemina)

- round-leaved dogwood (Cornus rugosa)

- American hazelnut (Corylus americana)

- alder-leaved buckthorn (Rhamnus alnifolia)

- soapberry (Shepherdia canadensis)

- blueberries (Vaccinium angustifolium and V. myrtilloides)

Trees

- balsam fir (Abies balsamea)

- sugar maple (Acer saccharum)

- paper birch (Betula papyrifera)

- American beech (Fagus grandifolia)

- white ash (Fraxinus americana)

- pines (Pinus banksiana, P. resinosa, and P. strobus)

- big-toothed aspen (Populus grandidentata)

- quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides)

- northern pin oak (Quercus ellipsoidalis)

- red oak (Quercus rubra)

- northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis)

- basswood (Tilia americana)

- hemlock (Tsuga canadensis)

Noteworthy Animals

Both sinkholes and caves provide habitat and hibernacula for bats.

Rare Plants

- Asplenium rhizophyllum (walking fern, state threatened)

- Dryopteris filix-mas (male fern, state special concern)

Rare Animals

None documented.

Biodiversity Management Considerations

Indiscriminate use of sinkholes in Alpena County as dumps and landfills still occurs, which results in groundwater pollution and degrades and obscures these fascinating features. Many sinkholes have also been filled in for farming. In some areas, erosion damage is occurring due to uncontrolled foot and vehicle traffic. Where sinkholes occur within forested systems, maintaining a mature, unfragmented buffer around their perimeters will help reduce soil erosion and runoff into sinkholes and may help limit the local seed source for invasive species distributed by wind or birds. Monitoring and control efforts to detect and remove invasive species will help maintain the ecological integrity of sinkholes and surrounding natural communities. Invasive species that may threaten the diversity and community structure of sinkholes include glossy buckthorn (Frangula alnus), common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica), Eurasian honeysuckles (especially Lonicera morrowii, L. tatarica, and L. xbella), Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii), multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora), autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata), European highbush cranberry (Viburnum opulus), and Norway maple (Acer platanoides).

Variation

Karst occurs in a variety of rock types in Michigan, including limestone, dolomite, and gypsum. To date, plant inventories have been focused on the limestone and dolomite karst, but insufficient data has been collected to determine whether there are floristic differences among these bedrock types.

Similar Natural Communities

Cave.

Places to Visit

- Fiborn Karst, Sault Sainte Marie State Forest Management Unit and Michigan Karst Conservancy, Mackinac Co.

- Rockport Karst, Rockport State Recreation Area, Presque Isle Co.

- Tomahawk Sinkholes, Sinkholes Pathway, Atlanta State Forest Management Unit, Presque Isle Co.

Relevant Literature

- Black, T.J. 1997. Evaporite karst of northern Lower Michigan. Carbonates and Evaporites 12(1): 81-83.

- Dorr, J.A., Jr., and D.F. Eschman. 1970. Geology of Michigan. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI. 470 pp.

- Faber-Langendoen, D., ed. 2001. Plant communities of the Midwest: Classification in an ecological context. Association for Biodiversity Information, Arlington, VA. 61 pp. + appendix (705 pp.).

- Michigan Karst Conservancy. http://www.caves.org/conservancy/mkc/michigan_karst_conservancy.htm.

- Nicoll, R.S. 1966. Development of karst features of the Silurian of the Northern Peninsula of Michigan and the Devonian of Indiana. Bloomington Indiana Grotto Newsletter 6(3): 23 pp.

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: February 20, 2026).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.