Dry Sand Prairie

Overview

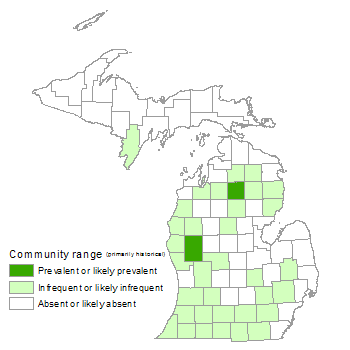

Dry sand prairie is a native grassland community dominated by little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), and Pennsylvania sedge (Carex pensylvanica). Vegetation is patchy and short in comparison to other prairie communities. The community occurs on loamy sands on well-drained to excessively well-drained, sandy glacial outwash plains and lakebeds both north and south of the climatic tension zone but is most common in northern Lower Michigan.

Rank

Global Rank: G3 - Vulnerable

State Rank: S2 - Imperiled

Landscape Context

Dry sand prairie occurs predominantly on the well-drained, nutrient-poor soils of sandy glacial outwash plains and lakebeds but may also occur on hilly, sandy deposits in ice-contact terrain and coarse-textured end and ground moraines. The lack of natural firebreaks on flat to gently rolling topography allows for broad-scale fires to carry across these landforms. Due to the variability of historic fires, dry sand prairies occurred as part of a shifting mosaic along with oak barrens in southern Michigan, oak-pine barrens in western Lower Michigan, and pine barrens or oak-pine barrens in northern Lower Michigan. Most of these former barrens communities have converted to forest as a result of fire suppression. Thus, dry sand prairies today are most commonly bordered by dry southern forest in the south, dry-mesic northern forest in western and northern Lower Michigan, or dry northern forest in central northern Lower Michigan.

Soils

Soils of dry sand prairies are typically very strongly acid to medium acid loamy sand with low water-retaining capacity.

Natural Processes

Historically, dry sand prairies were maintained in an open condition as a result of frequent fires, droughty soils, and in northern Lower Michigan, by frequent growing-season frosts. Fire frequency depended on a variety of factors such as type and volume of fuel, topography, and natural firebreaks. Prior to European settlement, intentional ignition by Native Americans and occasional lightning strikes were the main sources of fire. In addition to creating and maintaining the open conditions of dry sand prairies, frequent fires also help preserve species diversity by promoting seed germination and seedling establishment, creating microsites for small species, increasing the availability of plant nutrients, and bolstering flowering and seed set.

The excessively drained, sandy soils of dry sand prairie act to perpetuate open conditions by limiting tree establishment, especially during periodic droughts. Growing-season frosts, which also limit tree establishment, especially by hardwoods, are particularly common in the High Plains Subsection of northern Lower Michigan. In this region, dry sand prairie frequently occurs along with pine barrens in lower elevation, flat outwash plains known as frost pockets.

Vegetation

The vegetation of dry sand prairie is typically low to medium in height and somewhat sparse with patches of bare soil common. The community is dominated by little bluestem, Pennsylvania sedge, and big bluestem, with scattered trees maintained in a shrub-like condition (e.g., grubs) by frequent fires, droughty soils, and in northern Michigan, by growing-season frosts. Species composition varies by region.

Common species of dry sand prairie in the High Plains Subsection include the following: Pennsylvania sedge, poverty grass (Danthonia spicata), hair grass (Avenella flexuosa), little bluestem, June grass (Koeleria macrantha), rice grass (Piptatherum pungens), rough fescue (Festuca altaica, state threatened), big bluestem, rough blazing star (Liatris aspera), harebell (Campanula rotundifolia), Hill’s thistle (Cirsium hillii, state special concern), pale agoseris (Agoseris glauca, state threatened), bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi), sand cherry (Prunus pumila), sweet fern (Comptonia peregrina), northern dewberry (Rubus flagellaris), low sweet blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium), jack pine (Pinus banksiana), red pine (Pinus resinosa), and northern pin oak (Quercus ellipsoidalis). Oak grubs of white oak (Quercus alba), black oak (Quercus velutina), and northern pin oak can be abundant in dry sand prairie and may also occur as widely scattered, open grown adults. White pine (Pinus strobus), red pine (P. resinosa), and jack pine can occur in dry sand prairie as seedlings, saplings, and widely scattered adults.

Common species of dry sand prairies in southern and western Lower Michigan includes the following species: little bluestem, Pennsylvania sedge, New Jersey tea (Ceanothus americanus), flowering spurge (Euphorbia corollata), wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana), long-bearded hawkweed (Hieracium longipilum), old field goldenrod (Solidago nemoralis), big bluestem, smooth pussytoes (Antennaria parlinii), wormwood (Artemisia campestris), butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosa), prairie heart-leaved aster (Symphyotrichum oolentangiense), poverty grass, common rockrose (Crocanthemum canadense), rough blazing star (Liatris aspera), wild lupine (Lupinus perennis), panic grass (Dichanthelium oligosanthes), northern dewberry (Rubus flagellaris), black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta), early goldenrod (Solidago juncea), and common spiderwort (Tradescantia ohiensis).

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Graminoids

- big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii)

- fork-tipped three-awned grass (Aristida basiramea)

- three-awned grass (Aristida purpurascens)

- wavy hair grass (Avenella flexuosa)

- Pennsylvania sedge (Carex pensylvanica)

- slender sand sedge (Cyperus lupulinus)

- poverty grass (Danthonia spicata)

- Scribner’s panic grass (Dichanthelium oligosanthes)

- fall witch grass (Digitaria cognata)

- purple love grass (Eragrostis spectabilis)

- rough fescue (Festuca altaica)

- June grass (Koeleria macrantha)

- rice grass (Piptatherum pungens)

- little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium)

- sand dropseed (Sporobolus cryptandrus)

Forbs

- pale agoseris (Agoseris glauca)

- smooth pussytoes (Antennaria parlinii)

- wormwood (Artemisia campestris)

- clasping milkweed (Asclepias amplexicaulis)

- butterfly-weed (Asclepias tuberosa)

- green milkweed (Asclepias viridiflora)

- harebell (Campanula rotundifolia)

- Hill’s thistle (Cirsium hillii)

- common rockrose (Crocanthemum canadense)

- prairie cinquefoil (Drymocallis arguta)

- flowering spurge (Euphorbia corollata)

- wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana)

- prairie-smoke (Geum triflorum)

- western sunflower (Helianthus occidentalis)

- long-bearded hawkweed (Hieracium longipilum)

- long-leaved bluets (Houstonia longifolia)

- hairy bush-clover (Lespedeza hirta)

- rough blazing-star (Liatris aspera)

- cylindrical blazing-star (Liatris cylindracea)

- northern blazing-star (Liatris scariosa)

- hoary puccoon (Lithospermum canescens)

- hairy puccoon (Lithospermum caroliniense)

- wild lupine (Lupinus perennis)

- wild bergamot (Monarda fistulosa)

- horse mint (Monarda punctata)

- blue toadflax (Nuttallanthus canadensis)

- prickly-pear (Opuntia humifusa)

- hairy beard-tongue (Penstemon hirsutus)

- prairie phlox (Phlox pilosa)

- jointweed (Polygonella articulata)

- early buttercup (Ranunculus fascicularis)

- black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta)

- old-field goldenrod (Solidago nemoralis)

- prairie heart-leaved aster (Symphyotrichum oolentangiense)

- silky aster (Symphyotrichum sericeum)

- goats-rue (Tephrosia virginiana)

- birdfoot violet (Viola pedata)

Shrubs

- bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi)

- New Jersey tea (Ceanothus americanus)

- sweetfern (Comptonia peregrina)

- sand cherry (Prunus pumila)

- Alleghany plum (Prunus umbellata)

- northern dewberry (Rubus flagellaris)

- low sweet blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium)

Trees

- jack pine (Pinus banksiana)

- red pine (Pinus resinosa)

- white pine (Pinus strobus)

- white oak (Quercus alba)

- northern pin oak (Quercus ellipsoidalis)

- black oak (Quercus velutina)

Noteworthy Animals

Ants, particularly the genus Formica, play an important role in mixing and aerating prairie soils as they continually build and abandon mounds, overturning large portions of prairie soil in the process. Other important species contributing to soil mixing and aeration include moles, mice, skunks, and badgers. Kirtland’s warbler breeds almost exclusively in the matrix landscape of dry sand prairie, pine barrens, and dry-northern forest of northern Lower Michigan.

Rare Plants

- Agoseris glauca (pale agoseris, state threatened)

- Amorpha canescens (leadplant, state special concern)

- Androsace occidentalis (rock-jasmine, state endangered)

- Aristida dichotoma (Shiner’s three-awned grass, presumed extirpated from Michigan)

- Aristida tuberculosa (beach three-awned grass, state threatened)

- Aster sericeus (western silvery aster, state threatened)

- Carex gravida (sedge, presumed extirpated from Michigan)

- Cirsium hillii (Hill’s thistle, state special concern)

- Digitaria filiformis (slender finger-grass, presumed extirpated from Michigan)

- Eryngium yuccifolium (rattlesnake-master, state threatened)

- Festuca scabrella (rough fescue, state threatened)

- Geum triflorum (prairie-smoke, state threatened)

- Liatris punctata (dotted blazing-star, presumed extirpated from Michigan)

- Linum sulcatum (furrowed flax, state special concern)

- Lithospermum incisum (narrow-leaved puccoon, presumed extirpated from Michigan)

- Panicum leibergii (Leiberg’s panic-grass, state threatened)

- Penstemon pallidus (pale beard-tongue, state special concern)

- Polygala incarnata (pink milkwort, presumed extirpated from Michigan)

- Prunus alleghaniensis var. davisii (Alleghany plum, state special concern)

- Ruellia humilis (hairy ruellia, state threatened)

- Scleria pauciflora (few-flowered nut-rush, state endangered)

- Scleria triglomerata (tall nut-rush, state special concern)

- Solidago missouriensis (Missouri goldenrod, state threatened)

- Tradescantia bracteata (long-bracted spiderwort, presumed extirpated from Michigan)

- Tradescantia virginiana (Virginia spiderwort, state special concern)

- Trichostema brachiatum (false pennyroyal, state threatened)

- Trichostema dichotomum (bastard pennyroyal, state threatened)

- Triplasis purpurea (sand grass, state special concern)

- Vaccinium cespitosum (dwarf bilberry, state threatened)

Rare Animals

- Ammodramus henslowii (Henslow’s sparrow, state special concern)

- Ammodramus savannarum (grasshopper sparrow, state special concern)

- Appalachia arcana (secretive locust, state special concern)

- Asio flammeus (short-eared owl, state endangered)

- Asio otus (long-eared owl, state threatened)

- Atrytonopsis hianna (dusted skipper, state threatened)

- Clemmys guttata (spotted turtle, state threatened)

- Elaphe o. obsoleta (black rat snake, state special concern)

- Emydoidea blandingii (Blanding’s turtle, state special concern)

- Erynnis p. persius (Persius duskywing, state threatened)

- Flexamia delongi (leafhopper, state special concern)

- Glyptemys insculpta (wood turtle, state special concern)

- Hesperia ottoe (Ottoe skipper, state threatened)

- Incisalia irus (frosted elfin, state threatened)

- Lanus ludovicianus migrans (migrant loggerhead shrike, state endangered)

- Lepyronia gibbosa (Great Plains spittlebug, state threatened)

- Lycaeides melissa samuelis (Karner blue, federal/state threatened)

- Microtus ochrogaster (prairie vole, state endangered)

- Papaipema beeriana (blazing star borer, state special concern)

- Prosapia ignipectus (red-legged spittlebug, state special concern)

- Pygarctia spraguei (Sprague’s pygarctia, state special concern)

- Pyrgus wyandot (grizzled skipper, state special concern)

- Schinia indiana (phlox moth, state endangered)

- Sistrurus c. catenatus (eastern massasauga, federal candidate species and state special concern)

- Speyeria idalia (regal fritillary, state endangered)

- Spiza americana (dickcissel, state special concern)

- Sturnella neglecta (western meadowlark, state special concern)

- Terrapene c. carolina (eastern box turtle, state special concern)

- Tyto alba (barn owl, state endangered)

Biodiversity Management Considerations

Conservation priorities for dry sand prairies include identifying, protecting, and managing existing remnants where they occur. Managing dry sand prairie requires frequent prescribed burning to protect and enhance plant species diversity and prevent encroachment of trees and tall shrubs. In addition to prescribed fire, brush cutting accompanied by stump application of herbicide is often an important component of prairie restoration. To reduce the impacts of management on fire-intolerant species it is important to consider a rotating schedule of prescribed burns in which adjacent management units are burned in alternate years. Alternating burn units provides refugia for fire-intolerant insect species that are then able to recolonize the burned areas. Avian species diversity is also enhanced by managing large areas as a mosaic of burned and unburned patches. In addition, many restoration sites may require the reintroduction of appropriate native species and genotypes as small, isolated prairie remnants are subject to reduced gene flow.

Controlling invasive species is a critical step in restoring and managing dry sand prairie. By outcompeting native species, invasives alter vegetation structure, reduce species diversity, and disrupt ecological processes. Invasive plants such as Canada bluegrass (Poa compressa), Kentucky bluegrass (P. pratensis), sheep sorrel (Rumex acetosella), and hawkweeds (Hieracium spp.) can be ubiquitous within dry sand prairie remnants yet their impacts on overall species composition and diversity have not been well studied. These widespread invasive species likely outcompete many native forb seedlings for nutrients, water, and space, and thereby, along with lack of fire, perpetuate low levels of native forb abundance within dry sand prairie remnants. Additional invasive species that threaten the diversity and community structure of dry sand prairie include spotted knapweed (Centaurea stoebe), common St. John’s-wort (Hypericum perforatum), leafy spurge (Euphorbia virgata), hoary alyssum (Berteroa incana), autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata), Eurasian honeysuckles (especially Lonicera morrowii, L. tatarica, and L. xbella), and black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia).

Variation

As described in the Vegetation section above, species composition varies across ecoregions. Dry sand prairies in the High Plains Subsection of north central Lower Michigan are subject to colder temperatures, growing-season frosts, and a shorter growing season than occurrences in southern Lower Michigan.

Similar Natural Communities

Dry-mesic prairie, hillside prairie, oak barrens, oak-pine barrens, and pine barrens.

Places to Visit

- Coolbough Natural Areas, Brooks Township, Newaygo Co.

- Indian Lake Southwest, Manistee National Forest, Newaygo Co.

- Newaygo Prairie Nature Sanctuary, Michigan Nature Association, Newaygo Co.

- Sischo Prairies, Manistee National Forest, Oceana Co.

- Shupac Lake, Grayling State Forest Management Unit, Crawford Co.

- Tussing Prairie, Manistee National Forest, Lake Co.

Relevant Literature

- Albert, D.A. 1995. Regional landscape ecosystems of Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin: A working map and classification. USDA, Forest Service, North Central Forest Experiment Station, St. Paul, MN.

- Bratton, S.P. 1982. The effects of exotic plant and animal species on nature preserves. Natural Areas Journal 2(3): 3-13.

- Chapman, K.A. 1984. An ecological investigation of native grassland in southern Lower Michigan. M.A. thesis, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, MI. 235 pp.

- Comer, P.J., D.A. Albert, H.A. Wells, B.L. Hart, J.B. Raab, D.L. Price, D.M. Kashian, R.A. Corner, and D.W. Schuen. 1995. Michigan’s presettlement vegetation, as interpreted from the General Land Office surveys 1816-1856. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. Digital Map.

- Harty, F.M. 1986. Exotics and their ecological ramifications. Natural Areas Journal 6(4): 20-26.

- Hauser, R.S. 1953. An ecological analysis of the isolated prairies of Newaygo County, Michigan. Ph.D. dissertation. Michigan State College, East Lansing, MI, 168 pp.

- Herkert, J.R., R.E. Szafoni, V.M. Kleen, and J.E. Schwegman. 1993. Habitat establishment, enhancement and management for forest and grassland birds in Illinois. Division of Natural Heritage, Illinois Department of Conservation, Natural Heritage Technical Publication #1, Springfield, IL. 20 pp.

- Kost, M.A. 2004. Natural community abstract for dry sand prairie. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 9 pp.

- Leach, M.K., and T.J. Givnish. 1996. Ecological determinants of species loss in remnant prairies. Science 273: 1555-1558.

- Panzer, R.D., D. Stillwaugh, R. Gnaedinger, and G. Derkowitz. 1995. Prevalence of remnant dependence among prairie- and savanna-inhabiting insects of the Chicago region. Natural Areas Journal 15: 101-116.

- Steuter, A.A. 1997. Bison. Pp. 339-347 in The tallgrass restoration handbook for prairies savannas and woodlands, ed. S. Packard, and C.F. Mutel. Island Press, Washington D.C. 463 pp.

For a full list of references used to create this description, please refer to the natural community abstract for Dry Sand Prairie.

More Information

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: January 19, 2026).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.