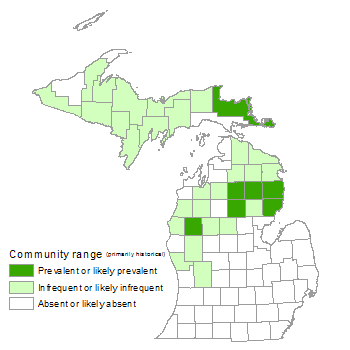

Overview

Pine barrens is a coniferous, fire-dependent savanna of scattered and clumped trees located north of the climatic tension zone in the northern Lower and Upper Peninsulas. The community occurs on level sandy outwash plains and sandy glacial lakeplains. The droughty sand soils are very strongly to strongly acid, with very poor water-retaining capacity. The community is dominated by jack pine (Pinus banksiana), with northern pin oak (Quercus ellipsoidalis) as a frequent canopy associate. Frequent fires, drought, and growing-season frosts maintain the open canopy conditions.

Rank

Global Rank: G3 - Vulnerable

State Rank: S2 - Imperiled

Landscape Context

Pine barrens typically occurs on level to gently sloping sandy outwash plains and sandy glacial lakeplains. The community occasionally occurs on sandy riverine terraces and moderate to steeply sloping ice-contact landforms that are located adjacent to broad outwash plains or lakeplains. The level topography and absence of natural fire breaks facilitate the spread of wildfire, which advances rapidly up adjacent moraines and ice-contact features. Where pine barrens occurs on pitted outwash and rolling topography, cold air collects in the depressions and forms frost pockets. Historically, pine barrens, dry sand prairie, and dry northern forest often occurred as a shifting mosaic, with species composition and community structure varying with fire frequency and fire intensity.

Soils

The soil is primarily excessively drained, very strongly to strongly acid sand, and relatively infertile. Thin bands of finer textured soil (loamy sand to sandy clay loam) are often present near moraines or ice-contact landforms. Such fine banding improves soil-water availability, resulting in more rapid tree growth and a faster rate of succession to forest.

Natural Processes

Frequent wildfire, in concert with drought, growing-season frosts, and low-nutrient soils, maintain open conditions in pine barrens. Fire allows the serotinous cones of jack pine to open and thereby facilitates seed dispersal. Fire is also essential in jack pine regeneration because it prepares the seedbed by exposing bare mineral soil, reducing competition from grasses, sedges, herbs, and woody vegetation, and increasing soil nutrient levels.

Vegetation

Jack pine typically dominates the open overstory. Red pine (Pinus resinosa) is often present, and widely scattered white pine (P. strobus) trees may also occur. Both red pine and white pine can form a sparse supercanopy above the scattered groves of jack pine. Northern pin oak, black cherry (Prunus serotina), and aspens (Populus spp.) are often found as stunted or young trees. Ground cover vegetation is characterized by a well developed, short shrub layer and numerous graminoid species. Blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium), sweet-fern (Comptonia peregrina), sand cherry (Prunus pumila), prairie willow (Salix humilis), and hazelnuts (Corylus spp.) make up most of the shrub layer when present. Poverty grass (Danthonia spicata), little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), and Pennsylvania sedge (Carex pensylvanica) are dominant herbaceous species across the range of this community. Other characteristic herbaceous species include big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), hair grass (Avenella flexuosa), prairie cinquefoil (Drymocallis arguta), porcupine grass (Hesperostipa spartea), June grass (Koeleria macrantha), rough blazing star (Liatris aspera), prairie heart-leaved aster (Symphyotrichum oolentangiense), and birdfoot violet (Viola pedata). Bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum) and reindeer lichen (Cladina spp.) are usually abundant.

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Graminoids

- big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii)

- wavy hair grass (Avenella flexuosa)

- prairie brome (Bromus kalmii)

- Pennsylvania sedge (Carex pensylvanica)

- slender sand sedge (Cyperus lupulinus)

- poverty grass (Danthonia spicata)

- panic grasses (Dichanthelium spp.)

- slender wheat grass (Elymus trachycaulus)

- purple love grass (Eragrostis spectabilis)

- rough fescue (Festuca altaica)

- June grass (Koeleria macrantha)

- rough-leaved rice grass (Oryzopsis asperifolia)

- rice grass (Piptatherum pungens)

- little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium)

Forbs

- pale agoseris (Agoseris glauca)

- pussytoes (Antennaria howellii and A. parlinii)

- wormwood (Artemisia campestris)

- harebell (Campanula rotundifolia)

- Hill’s thistle (Cirsium hillii)

- common rockrose (Crocanthemum canadense)

- wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana)

- western sunflower (Helianthus occidentalis)

- hawkweeds (Hieracium kalmii and H. venosum)

- long-leaved bluets (Houstonia longifolia)

- rough blazing-star (Liatris aspera)

- cylindrical blazing-star (Liatris cylindracea)

- northern blazing-star (Liatris scariosa)

- hoary puccoon (Lithospermum canescens)

- hairy puccoon (Lithospermum caroliniense)

- cow-wheat (Melampyrum lineare)

- horse mint (Monarda punctata)

- blue toadflax (Nuttallanthus canadensis)

- racemed milkwort (Polygala polygama)

- jointweed (Polygonella articulata)

- goldenrods (Solidago hispida, S. nemoralis, and S. ptarmicoides)

- slender ladies’-tresses (Spiranthes lacera)

- smooth aster (Symphyotrichum laeve)

- birdfoot violet (Viola pedata)

Ferns

- bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum)

Lichens

- reindeer lichens (Cladina spp.)

Shrubs

- serviceberries (Amelanchier spicata and others)

- bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi)

- sweetfern (Comptonia peregrina)

- trailing arbutus (Epigaea repens)

- sand cherry (Prunus pumila)

- Alleghany plum (Prunus umbellata)

- northern dewberry (Rubus flagellaris)

- prairie willow (Salix humilis)

- low sweet blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium)

- Canada blueberry (Vaccinium myrtilloides)

Trees

- jack pine (Pinus banksiana)

- red pine (Pinus resinosa)

- white pine (Pinus strobus)

- aspens (Populus grandidentata and P. tremuloides)

- black cherry (Prunus serotina)

- northern pin oak (Quercus ellipsoidalis)

Noteworthy Animals

Pine barrens and surrounding dry sand prairie habitat support a rich diversity of invertebrates including numerous species of butterflies, skippers, grasshoppers, and locusts. Pine barrens are essential to the survival of the Kirtland’s warbler, an endangered songbird that breeds almost exclusively in the pine barrens of northern Lower Michigan.

Rare Plants

- Agoseris glauca (pale agoseris, state threatened)

- Cirsium hillii (Hill's thistle, state special concern)

- Festuca scabrella (rough fescue, state threatened)

- Oryzopsis canadensis (Canada rice-grass, state threatened)

- Prunus alleghaniensis var. davisii (Alleghany plum, state special concern)

Rare Animals

- Ammodramus savannarum (grasshopper sparrow, state special concern)

- Appalachia arcana (secretive locust, state special concern)

- Atrytonopsis hianna (dusted skipper, state threatened)

- Dendroica discolor (prairie warbler, state endangered)

- Dendroica kirtlandii (Kirtland’s warbler, federal/state endangered)

- Erynnis p. persius (Persius duskywing, state threatened)

- Hesperia ottoe (ottoe skipper, state threatened)

- Incisalia henrici (Henry’s elfin, state special concern)

- Incisalia irus (frosted elfin, state threatened)

- Lepyronia gibbosa (Great Plains spittlebug, state threatened)

- Lycaeides melissa samuelis (Karner blue, federal endangered and state threatened)

- Prosapia ignipectus (red-legged spittlebug, state special concern)

- Pygarctia spraguei (Sprague’s pygarctia, state special concern)

- Pyrgus centaureae wyandot (grizzled skipper, state special concern)

- Terrapene c. carolina (eastern box turtle, state special concern)

- Tympanuchus phasianellus (sharp-tailed grouse, state special concern)

Biodiversity Management Considerations

Fire is the single most significant factor in preserving the pine barrens landscape. Where remnants of pine barrens persist, the use of prescribed fire is an imperative management tool for maintaining an open canopy, promoting high levels of grass and forb diversity, deterring the encroachment of woody vegetation and invasive plants, and limiting the success of overstory dominants. When feasible, prescribed fire management for pine barrens should encompass other adjacent fire-dependent upland and wetland communities such as dry sand prairie, dry northern forest, dry-mesic northern forest, bog, poor fen, intermittent wetland, northern fen, and northern wet meadow. Where rare animal species are a management concern, burning strategies should allow for ample refugia to facilitate effective post-burn recolonization. Degraded barrens that have been long deprived of fire and have converted to closed canopy forest or woodland may require mechanical thinning or girdling prior to implementation of prescribed fire.

Destructive timber exploitation of pines (1890s) and oaks (1920s) combined with post-logging slash fires likely destroyed or degraded many pine barrens. In addition, fire suppression policies instituted in the 1920s resulted in the succession of many open pine barrens to closed canopy forests dominated by jack pine. Many sites formerly occupied by pine barrens were also converted to pine plantations. The fragments of pine barrens that remain often lack the full complement of conifers; scattered red pine and white pine, which create a supercanopy, were widely harvested. In addition to simplified overstory structure, these communities are often depauperate in floristic diversity as the result of fire suppression, livestock grazing, off-road-vehicle activity, and the subsequent invasion of non-native species.

Monitoring and control efforts to detect and remove invasive species before they become widespread are critical to the long-term viability of pine barrens. By outcompeting native species, invasives alter vegetation structure, reduce species diversity, and disrupt ecological processes. The following invasive species can be significant components of the herbaceous layer of degraded pine barrens: spotted knapweed (Centaurea stoebe), hawkweeds (Hieracium spp.), Canada bluegrass (Poa compressa), Kentucky bluegrass (P. pratensis), and sheep sorrel (Rumex acetosella). These widespread invasive species likely outcompete many native forb seedlings for nutrients, water, and space, and thereby, along with lack of fire, perpetuate low levels of native forb abundance within degraded pine barren remnants. Several additional invasive species that have potential to reduce diversity and alter community structure in the future include common St. John’s-wort (Hypericum perforatum), autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata), common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica), and potentially, Eurasian honeysuckles (especially Lonicera morrowii, L. tatarica, and L. xbella).

Variation

Red pine and white pine were occasionally common canopy associates. Tree growth and rate of succession is lower in pine barrens found in cold, low-elevation landforms of the interior of Michigan than on lakeplains with lake-moderated climates or high-elevation landforms with better soils and more moderate climates.

Similar Natural Communities

Dry sand prairie, dry northern forest, Great Lakes barrens, oak barrens, and oak-pine barrens.

Places to Visit

- Baraga Plains, Baraga State Forest Management Unit, Baraga Co.

- Frog Lake Barrens, Grayling State Forest Management Unit, Crawford Co.

- Little Bear Lake Barrens, Gaylord State Forest Management Unit, Otsego Co.

- Shupac Lake Barrens, Grayling State Forest Management Unit, Crawford Co.

Relevant Literature

- Comer, P.J. 1996. Natural community abstract for pine barrens. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. 3 pp.

- Curtis, J.T. 1959. The vegetation of Wisconsin. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, WI. 657 pp.

- Faber-Langendoen, D. 1993. A proposed classification for savannas in the Midwest. Background paper for the Midwest Oak Savanna Conference. 18 pp.

- Kashian, D.M., B.V. Barnes, and W.S. Walker. 2003. Landscape ecosystems of northern Lower Michigan and the occurrence and management of the Kirtland’s warbler. Forest Science 49: 140-159.

- McAtee, W.L. 1920. Notes on the jack pine plains of Michigan. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 47: 187-190.

- Simard, A.J., and R.W. Blank. 1982. Fire history of a Michigan jack pine forest. Michigan Academician 15: 59-71.

- Stocks, B.J. 1989. Fire behavior in mature jack pine. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 19: 783-790.

- Vogl, R.J. 1970. Fire and the northern Wisconsin pine barrens. Proceedings of the Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference 10: 175-209.

- Vora, R.S. 1993. Moquah barrens: Pine barrens restoration experiment initiated in Chequemagon National Forest. Restoration and Management Notes 11(1): 39-44.

- Walker, W.S., B.V. Barnes, and D.M. Kashian. 2003. Landscape ecosystems of the Mack Lake burn, northern Lower Michigan, and the occurrence of the Kirtland’s warbler. Forest Science 49: 119-139.

- Whitney, G.G. 1986. Relation of Michigan’s presettlement pine forests to substrate and disturbance history. Ecology 67(6): 1548-1559.

For a full list of references used to create this description, please refer to the natural community abstract for Pine Barrens.

More Information

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: February 27, 2026).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.