Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake

About the Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake

The eastern massasauga rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus) is a unique and fascinating part of Michigan's natural heritage. It is Michigan's only venomous snake, and one of only two rattlesnake species that occur in the Great Lakes region. It is a small- to medium-sized snake, with adult lengths averaging 2 to 3 feet. The eastern massasauga is primarily associated with wetland habitats but some populations also utilize adjacent upland habitats for parts of its life history. Although it's venomous, the massasauga is a timid snake. It prefers to avoid detection by hiding under vegetation, woody debris or other cover or remaining motionless and relying on its cryptic coloration. When it is disturbed or encountered in open habitat, the massasauga prefers to move to a more hidden location. Most people in Michigan may never even see a massasauga in the wild because of its secretive behavior. The massasauga also appears to have strong site fidelity, often returning to the same hibernation site or area each year. Studies to date also have found that massasaugas were not be able to survive the winter when moved to a new area outside their home range presumably because they were not able to find suitable hibernation sites.

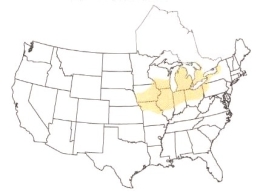

Michigan appears to be the last stronghold for this species with more massasauga populations currently than any other state or province within the species' range. Thus, the eastern massasauga's long-term viability in Michigan has important implications for this species' persistence rangewide. However, Michigan's massasauga population also has declined. The primary reasons for the massasauga's decline in Michigan and rangewide are habitat loss and fragmentation, human persecution or indiscriminant killing, and illegal collection.

The eastern massasauga was once common across its range but has declined dramatically since the mid-1970's, according to a 1998 eastern massasauga status assessment conducted by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Massasaugas now mainly occur in disjunct, isolated populations and have been afforded some level of legal protection in every state or province within its range.

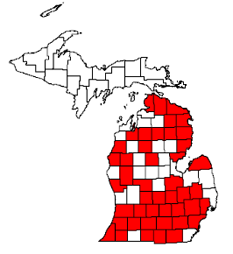

Michigan Distribution

Historically, eastern massasaugas were found throughout the Lower Peninsula and on Bois Blanc Island. Within the last decade, eastern massasaugas have been reported from about 150 sites in 50 counties. These sightings appear to cluster in several regions across the Lower Peninsula, indicating areas where massasaugas may be concentrated. These include Oakland, Livingston, Jackson and Washtenaw counties in southeast Michigan, Allegan, Barry and Kalamazoo counties in southwest Michigan, and Iosco, Crawford and Kalkaska counties in northern Michigan. Nearly one- third of the historical occurrences in the state has not been reconfirmed in the past ten years. Massasaugas have not been reported from Branch, Ingham, Shiawassee, Macomb, Huron, Clare, Oscoda, Montmorency and Emmet counties since prior to 1980 (some since the early 1900's). It is important to note, however, that a statewide, systematic field survey for this species has not been conducted. Also, massasaugas are highly cryptic and difficult to observe in its natural habitat. Therefore, massasaugas may still be present in areas that lack recent, as well as historical, records.

Life History & Ecology

Eastern massasaugas have been found in a variety of wetland habitats, including bogs, fens, shrub swamps, wet meadows, marshes, moist grasslands, wet prairies, and floodplain forests (Hallock 1990, Harding 1997). Populations in southern Michigan are typically associated with open wetlands, particularly prairie fens, while those in northern Michigan are better known from lowland coniferous forests, such as cedar swamps (Legge and Rabe 1999). Massasaugas also appear to exhibit seasonal shifts in habitat utilization. They generally occupy wetland habitats in the spring, fall, and winter, but in the summer, snakes migrate to drier, upland sites, ranging from forest openings to old fields, agricultural lands and prairies. In general, structural characteristics of a site appear to be more important than vegetative characteristics for determining habitat suitability (Beltz 1992). Specifically, all known sites appear to be characterized by the following: (1) open, sunny areas intermixed with shaded areas, presumably for thermoregulation; (2) presence of the water table near the surface for hibernation; and (3) variable elevations between adjoining lowland and upland habitats (Beltz 1992).

Massasaugas usually are active between April and late October. Spring emergence typically starts in late March and early April as groundwater levels rise and ground temperature approaches air temperature (Harding 1997, Szymanski 1998). Massasaugas spend most of the time in the spring basking on elevated sites such as sedge and grass hummocks, muskrat and beaver lodges, or dikes and other embankments. Individuals may spend up to several weeks in the wetlands near their hibernation sites before moving to their summer habitats (Johnson 1995). This seasonal shift in habitat use appears to vary regionally and among populations (Szymanski 1998). In Wisconsin, King (1997) documented only gravid females dispersing to the drier uplands to have their young, while the males and non-gravid females remained in the wetlands. Moore and Gillingham (2006) followed the general movement patterns of massasaugas at a fen in Michigan and found emergence from hibernacula occurred in early to mid-April, then the snakes moved out of buckthorn dominated scrub\shrub or lowland hardwood floodplain to open and slightly higher elevation (approximately 5015m) emergent or scrub/shrub wetland during summer. In mid-October, snakes returned back to their hibernacula in lowland hardwood floodplain.

Mating occurs in the spring, summer and fall (Reinert 1981, Vogt 1981, Harding 1997). The females give birth to litters of 5 to 20 live young in August or early September in mammal burrows or fallen logs in the uplands (Vogt 1981, Harding 1997). The young are born enclosed in a thin egg sac from which they soon emerge. Female massasaugas reach sexual maturity at three or four years of age, after which they have been reported to reproduce both annually and biennially in different parts of their range (Reinert 1981, Seigel 1986, Harding 1997).

Massasaugas usually hibernate in the wetlands in crayfish or small mammal burrows. They also have been known to hibernate in tree roots and rock crevices as well as submerged trash, barn floors, and basements (Johnson and Menzies 1993). Hibernation sites are located below the frost line, often close to groundwater level. The presence of water that does not freeze is critical to hibernaculum suitability (Johnson 1995). Individuals tend to return to the same hibernation site each year (Prior 1991). This species tends to hibernate singly or in small groups of two or three (Johnson and Menzies 1993).

Massasauga home ranges and movement distances can be quite variable, which may be due to differing habitat structure and resource availability at the various sites (Moore and Gillingham 2006). King (1997) reported mean home ranges of approximately 5 to 7 acres for neonates and gravid females, 17 acres for non-gravid females and 398 acres for males. He also recorded mean range lengths of 0.03 mile for neonates, 0.2 mile for non-gravid females, 0.4 mile for gravid females, and 0.8 mile for males. Other studies have reported mean home ranges of 0.65 acres to 95 acres (Reinert and Kodrich 1982, Johnson 1995, Moore and Gillingham 2006, Durbian et al. 2008). The most recent information on mean home ranges for massasaugas in Wisconsin and Missouri is 9 acres for females, 13 for gravid females, 95 for males, and 2 for neonates (Durbian et al. 2008). Reported maximum movements range from 0.1 mile in Michigan (Hallock 1990) to 2 miles in Wisconsin (King 1997).

Massasaugas feed primarily on small mammals such as voles, moles, jumping mice, and shrews. They also will consume other snake species and occasionally birds and frogs. Young massasaugas are more dependent on cold-blooded prey, particularly frogs (Vogt 1981). Natural predators for the massasauga, particularly the eggs and young, include hawks, skunks, raccoons, and foxes (Vogt 1981). Massasaugas also are commonly killed by humans.

When they are threatened, eastern massasaugas will typically remain motionless, relying on their cryptic coloration to blend into their surroundings. They sound their rattle when alarmed but will occasionally strike without rattling when surprised. The rattle sound of the massasauga is different than the traditional sound of other rattlesnake species. It is best described as a buzzing sound, similar to one made by a bee stuck in a spider web. Although the temperaments of individual snakes vary widely, this species is generally considered non-aggressive. It is unusual for the species to strike unless it is directly disturbed (Johnson and Menzies 1993), and bites to humans are rare. Although the venom is highly toxic, fatalities are very uncommon because the species' short fangs can inject only a small volume (Klauber 1972). Small children and people in poor health are thought to be at greatest risk. Michigan poison control centers report about 16 massasauga bites in a typical year.

Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake Identification

- Gray or grayish brown with dark blotches edged in white and spots down back and sides

- 18.5-30 inches long; record 39.5 inches long

- Belly blackish, not patterned

- Heavy-bodied; often found coiled

- Gives birth to live young

- Pit on each side of head between eye and nostril

- Cat-like pupils

- Wide, triangular head

- Distinct segmented rattle

- Tail thick, squarish; does not taper to a point like all other snakes in Michigan

- Does not always rattle a warning; relies on pattern and remaining motionless to go undetected

- Scales keeled; anal scale single

Look-Alike Snakes

Eastern Milk Snake (Lampropeltis triangulum triangulum)

- 24-36 inches; Record 52 inches

- Light gray or tan with brown or reddish-brown, black-bordered blotches running down back

- Young similar to adults but blotches brighter red

- Often Y- or V-shaped light marking on top of neck

- Belly white with black checkerboard pattern

- Scales smooth; anal scale single

- Lays eggs

Eastern Fox Snake (Elaphe vulpine gloydi)

- Eastern subspecies in Southeast Lower Peninsula only; western subspecies in Upper Peninsula only

- 36-54 inches; record 70.5 inches

- Yellowish to light brown with black or dark brown blotches; head reddish or orangish

- Belly yellow with black checkboard pattern

- Scales weakly keeled; anal scale divided

- Lays eggs

- Eastern subspecies is State Threatened

Eastern Hog Nose Snake (Heterodon platyrhinos)

- 20-33 inches; record 45.5 inches

- Most have dark spots/blotches on yellowish, reddish or brown background, but some solid black, brown or olive

- When threatened, spreads neck to display two prominent black eyespots on neck and hisses; may turn over and play dead

- Heavy-bodied

- Flat head with upturned snout

- Belly yellow-gray with greenish gray pattern

- Scales keeled; anal scale divided

- Lays eggs

Photo by Earl Wolf

Photo by Earl Wolf

Northern Water Snake (Nerodia sepidon)

- 24-42 inches; record 55 inches

- Light brown with dark brown or blackish blotches; older individuals may appear uniformly black

- Belly cream with irregular rows of reddish or blackish half moon crescents

- Usually found in or near water

- Scales keeled; anal scale divided

- Gives birth to live young

References

- Beltz, E. 1992. Final report on the status and distribution of the eastern massasauga, Sistrurus catenatus catenatus (Rafinesque 1818), in Illinois. Unpublished report to the Illinois Department of Conservation, Division Natural Heritage, Springfield, IL. 36 pp.

- Durbian, F. E., R. S. King, T. Crabill, H. Lambert-Doherty, and R. A. Seigel. 2008. Massasauga home range patterns in the Midwest. J. of Wildl. Manage.72(3):754-759.

- Hallock, L. A. 1990. Master's Thesis: Habitat utilization, diet and behavior of the eastern massasauga (S. c. catenatus) in southern Michigan. Dept. of Zool., Michigan State Univ., E. Lansing, MI. 31 pp.

- Harding, J. H. 1997. Amphibians and reptiles of the Great Lakes region. The University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI. 378 pp.

- Johnson, B. and V. Menzies, eds. 1993. Proceedings of the International Symposium and Workshop on the Conservation of the Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake Sistrurus catenatus catenatus, May 8-9, 1992. Metro Toronto Zoo, Ontario, Canada. 136 pp.

- Johnson, G. 1995. Spatial ecology, habitat preference, and habitat management of the eastern massasauga, Sistrurus c. catenatus, in a New York weakly-minerotrophic peatland. Dissertation. SUNY, College of Environmental Science and Forestry, Syracuse, NY. 222pp.

- King, R. S. 1997. Preliminary findings of a habitat use and movement patterns study of the eastern massasauga rattlesnake in Wisconsin. Unpublished report to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Green Bay, WI. 32 pp.

- Klauber, L.M. 1972. Rattlesnakes: Their habits, life histories, and influence on mankind, 2nd ed. Univ. of Calif. Press, Berkeley. 1533 pp.

- Legge, J. T. 1996. Final report on the status and distribution of the eastern massasauga rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus) in Michigan. Unpublished report to the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 3 Office, Fort Snelling, MN. 17 pp. + appendix.

- Legge, J. T. and M. R. Rabe. 1994. Summary of recent sightings of the eastern massasauga rattlesnake (S. c. catenatus) in Michigan and identification of significant population clusters. Unpublished report to the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 3 Office, Fort Snelling, MN. 8 pp.

- Legge, J. T. and M. R. Rabe. 1999. Habitat changes and trends affecting selected populations of Sistrurus catenatus catenatus (eastern massasauga) in Michigan. Pp. 155-164 in Fifteenth North American Prairie Conference Proceedings, edited by C. Warwick. Oregon: The Natural Areas Association.

- Moore, J. A. and J. C. Gillingham. 2006. Spatial ecology and multi-scale habitat selection by a threatened rattlesnake: The Eastern massasauga (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus). Copeia 4:742-751.

- Prior, K. A. 1991. Eastern massasauga rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus) biology, status, and management: A guide for recovery. Unpublished discussion paper for Canadian Parks Service. 40 pp.

- Reinert, H. K. 1981. Reproduction by the massasauga (S. c. catenatus). Amer. Midl. Nat. 105: 393-395.

- Reinert, H. K. and W. R. Kodrich. 1982. Movements and habitat utilization by the massasauga, S. c. catenatus. J. Herpetol. 16: 162-171.

- Seigel, R. A. 1986. Ecology and conservation of an endangered rattlesnake, S. catenatus, in Missouri, U.S.A. Biol. Conserv. 35: 333-346.

- Szymanski, J. A. 1998. Status assessment for the eastern massasauga (Sistrurus c. catenatus). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Fort Snelling, MN. 19 pp + apps.

- Vogt, R. C. 1981. Natural history of amphibians and reptiles of Wisconsin. Milwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee, WI. 205 pp.