Floodplain Forest

Overview

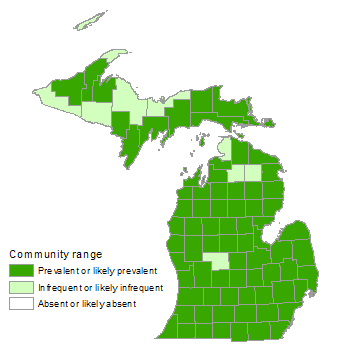

Floodplain forest is a bottomland, deciduous or deciduous-conifer forest community occupying low-lying areas adjacent to streams and rivers of third order or greater, and subject to periodic over-the-bank flooding and cycles of erosion and deposition. Species composition and community structure vary regionally and are influenced by flooding frequency and duration. Silver maple (Acer saccharinum) and green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica) are typically major overstory dominants. Floodplain forests occur along major rivers throughout the state, but are most extensive in the Lower Peninsula. Species richness is greatest in the southern Lower Peninsula, where many floodplain species reach the northern extent of their range.

Rank

Global Rank: G3? - Vulnerable (inexact)

State Rank: S3 - Vulnerable

Landscape Context

Floodplain forests are located along streams and rivers of third order or greater. River floodplains occur within the four major physiographic systems (landforms) of Michigan: moraine, outwash plain, ice-contact terrain, and lakeplain. However, because the present drainage system is closely associated with drainage patterns that developed during the retreat of the Wisconsinan glaciers, river floodplains most frequently occur within former glacial meltwater (outwash) channels. River floodplains occur within broad outwash plains as well as narrow outwash plains situated between end moraines, and the river channels occasionally cut through moraines. In glacial lakeplains, large stretches of rivers flow through sand channels that formed where glacial meltwater carried and deposited sand into the proglacial lakes, but other stretches cut through fine silty and clayey lacustrine sediments.

Soils

Soil is highly variable and strongly correlated with fluvial landforms. The coarsest sediment is deposited on the natural levee, immediately adjacent to the stream channel, where the soil texture is often sandy loam to loam. Progressively finer soil particles are deposited with increasing distance from the stream. Soil texture of the first bottom is often silt loam, with silty clay loam to clay-textured soil often occurring in swales and backswamps. Cycles of periodic over-the-bank flooding followed by soil aeration when the floodwaters recede generally prevent the accumulation of organic soils. However, an accumulation of sapric peat can develop farther from the river due to a relatively low flood frequency, low flow velocity, and prolonged soil saturation resulting from a high water table. Floodplain soils are generally circumneutral to mildly alkaline. Slightly acid soils are generally only found on hummocks of organic soil in backswamps or meander-scar swamps. Floodplain soils are characterized by high nutrient availability and an abundance of soil water throughout much of the growing season.

Natural Processes

Direct interaction between terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems occurs in floodplain forests through the processes of over-the-bank flooding, bank cutting, and sedimentation. Over-the-bank flooding can directly cause treefall or indirectly lead to windthrow through increased soil saturation. Spring floodwaters often carry ice floes and debris that can scour trees, leading to the development of multiple-stemmed canopy trees. The input of organic matter from the floodplain forest provides sources of energy for aquatic organisms. Shade from streamside vegetation moderates temperature regimes in aquatic systems, preventing excessive warming of the river during summer months. Woody debris from floodplain vegetation influences the development of channel morphology and provides necessary habitat for many aquatic organisms. Riparian vegetation reduces overland water flow and sediment transport. Nutrient uptake by floodplain vegetation and denitrification by soil bacteria decrease terrestrial inputs of nutrients into aquatic systems. Such processes are especially important in landscapes dominated by agricultural or urban land cover, where nutrient input from upland ecosystems is typically high.

The dynamic process of channel migration creates a diversity of landscape features in floodplains. Hydrogeomorphic processes such as over-the-bank flooding, transport and deposition of sediment, and erosive and abrasive water movement cause the floodplains of large rivers to exhibit a variety of fluvial landforms, each of which is associated with a particular kind of vegetation. Such fluvial landforms are distinguished by their size, shape, elevation, soil characteristics, and location in relation to the stream channel. Several of the most characteristic fluvial landforms are natural levee, first bottom, backswamp, oxbow, and terrace. A key series of relationships link the physiography of the river valley with that of the upland landscape. Basin size, topographic relief, and geologic parent material of the upland landscape determine river discharge, river grade, sediment load, and sediment type. These factors strongly influence the formation of fluvial landforms through the hydrogeomorphic processes of erosion, deposition, and channel migration. The size, shape, and diversity of fluvial landforms in a river floodplain and their spatial pattern are the result of the interaction between a river and the local landscape. Because physiographic systems are characterized by their topographic form and parent material, floodplains within different physiographic systems are characterized by differences in stream gradient, channel pattern, local hydrology, and fluvial landforms. When a river flows through a flat region, such as a broad outwash plain or a lakeplain, a wide, continuous floodplain develops. Within these wide floodplains, extensive lateral channel migration and the deposition of progressively finer-textured sediment with increasing distance from the river lead to the formation of a variety of fluvial landforms. With uniformly low topography and a relatively high water table, the broad first bottom of rivers within outwash plains and lakeplains is periodically inundated during the growing season. In contrast, both the higher topographic relief and finer-textured parent material of moraines encourage the development of narrow river valleys with more restricted floodplains and a reduced duration of flooding. The development of narrow valleys also occurs where rivers occupy narrow outwash channels situated between end moraines. The high topographic relief, relatively steep slope gradients, and fine-textured soil of morainal landscapes restrict lateral channel migration, resulting in narrow, sinuous floodplains that are frequently dissected by a series of higher terraces. The frequency of over-the-bank flooding in morainal landscapes is generally less than that in outwash plains and lakeplains. Instead, groundwater plays a stronger role, and constant soil saturation due to groundwater seepage often results in localized accumulations of organic soil.

Vegetation

As a result of the dynamic, local nature of natural disturbance along stream channels, a typical floodplain forest consists of many small patches of vegetation with different species composition, and successional stages often correlated with fluvial landforms. Within a single floodplain forest, vegetation changes along a gradient of flooding frequency and duration. In addition to local variation in species composition and structure within a site, there are major regional differences in species composition between floodplain forests in northern and southern Michigan. In both regions, dominant tree species nearly always include silver maple and green ash. Previously, American elm (Ulmus americana) was also a major dominant, but it has been largely eliminated from the canopy by Dutch elm disease. Numerous other species can be important, especially in the southernmost watersheds, resulting in complex patterns of species dominance.

Characteristic ground flora in southern Michigan include wild ginger (Asarum canadense), wood nettle (Laportea canadensis), stinging nettle (Urtica dioica), green dragon (Arisaema dracontium), purple meadow rue (Thalictrum dasycarpum), bluejoint grass (Calamagrostis canadensis), Virginia wild rye (Elymus virginicus), false nettle (Boehmeria cylindrica), carrion flower (Smilax ecirrata), starry false Solomon’s seal (Maianthemum stellatum), lizard’s tail (Saururus cernuus), Gray’s sedge (Carex grayi), Muskingum sedge (C. muskingumensis), wood reedgrass (Cinna arundinacea), southern blue flag (Iris virginica), clearweed (Pilea pumila), swamp buttercup (Ranunculus hispidus), golden ragwort (Packera aurea), ostrich fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris), sensitive fern (Onoclea sensibilis), jewelweed (Impatiens capensis), skunk cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus), late goldenrod (Solidago gigantea), and fringed loosestrife (Lysimachia ciliata). Compared to southern Michigan floodplains, grasses and sedges account for a larger portion of the ground flora in floodplains of northern Michigan. Grasses and sedges common to both northern and southern floodplain forests include bluejoint grass, Virginia wild rye, cut grass (Leersia oryzoides), fowl manna grass (Glyceria striata), lake sedge (Carex lacustris), great bladder sedge (C. intumescens), hop sedge (C. lupulina), and fringed sedge (C. crinita).

Fluvial landforms, defined by their size, shape, elevation, soil, and position in relation to the stream channel, exert a strong influence on the patterning of floodplain vegetation. New land deposits immediately adjacent to the stream channel are dominated by black willow (Salix nigra) and cottonwood (Populus deltoides). The natural levee is often dominated by silver maple and green ash, but a variety of additional tree species may also be common, including basswood (Tilia americana), swamp white oak (Quercus bicolor), bur oak (Q. macrocarpa), sycamore (Platanus occidentalis), hackberry (Celtis occidentalis), box elder (Acer negundo), and shagbark hickory (Carya ovata). The low frequency and short duration of flooding on the levee and second bottom result in dense cover of shrubs and small trees such as musclewood (Carpinus caroliniana), alternate-leaved dogwood (Cornus alternifolia), gray dogwood (C. foemina), prickly ash (Zanthoxylum americanum), redbud (Cercis canadensis), hawthorns (Crataegus spp.), spicebush (Lindera benzoin), nannyberry (Viburnum lentago), elderberry (Sambucus canadensis), bladdernut (Staphylea trifolia), and choke cherry (Prunus virginiana). Adjacent to the levee, the first bottom flat is flooded more frequently and for a longer period, limiting the tree canopy to silver maple, green ash, and American elm. Shrubs are typically rare within the first bottom flat, but vines including riverbank grape (Vitis riparia), poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia), and moonseed (Menispermum canadense) may be abundant. Small depressions and swales where tree canopy coverage is low are often dominated by buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis). Second bottoms are typically dominated by the same tree species common to the levee but can also include bitternut hickory (Carya cordiformis), butternut (Juglans cinerea), black walnut (J. nigra), black maple (Acer nigrum), and white ash (Fraxinus americana). Shrubs may also be abundant on second bottoms. Areas where organic soil accumulates, such as groundwater seepages, backswamps, and meander-scar swamps are often dominated by black ash (Fraxinus nigra), yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis), red maple (Acer rubrum), tamarack (Larix laricina), northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis), white pine (Pinus strobus), and hemlock (Tsuga canadensis), with conifer coverage especially high in the northern part of the state and often lacking in southern Lower Michigan. Species such as royal fern (Osmunda regalis), dwarf raspberry (Rubus pubescens), and New York fern (Thelypteris noveboracensis) are often abundant in the ground cover of these fluvial landforms. Low terraces, within the floodplain but above the influence of floodwaters, are often dominated by American beech (Fagus grandifolia) and sugar maple (Acer saccharum), often with black maple in the southern Lower Peninsula and hemlock in the northern Lower and Upper Peninsulas. Higher terraces are dominated by oak and hickory in the southern part of the state, and oak and pine in the north.

For information about plant species, visit the Michigan Flora website.

Plant Lists

Graminoids

- blue-joint (Calamagrostis canadensis)

- sedges (Carex crinita, C. grayi, C. hirtifolia, C. intumescens, C. lacustris, C. lupulina, C. muskingumensis, C. stricta, C. tuckermanii, and others)

- wood reedgrass (Cinna arundinacea)

- beak grass (Diarrhena obovata)

- riverbank wild-rye (Elymus riparius)

- Virginia wild-rye (Elymus virginicus)

- fowl manna grass (Glyceria striata)

- cut grass (Leersia oryzoides)

- white grass (Leersia virginica)

Forbs

- wild leeks (Allium burdickii and A. tricoccum)

- wild garlic (Allium canadense)

- green dragon (Arisaema dracontium)

- jack-in-the-pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum)

- wild ginger (Asarum canadense)

- false nettle (Boehmeria cylindrica)

- blue cohoshes (Caulophyllum giganteum and C. thalictroides)

- turtlehead (Chelone glabra)

- honewort (Cryptotaenia canadensis)

- flat-topped white aster (Doellingeria umbellata)

- white trout lily (Erythronium albidum)

- yellow trout lily (Erythronium americanum)

- green-stemmed joe-pye-weed (Eutrochium purpureum)

- false mermaid (Floerkea proserpinacoides)

- wild geranium (Geranium maculatum)

- white avens (Geum canadense)

- Jerusalem-artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus)

- cow-parsnip (Heracleum maximum)

- great waterleaf (Hydrophyllum appendiculatum)

- Canada waterleaf (Hydrophyllum canadense)

- Virginia waterleaf (Hydrophyllum virginianum)

- jewelweed (Impatiens capensis)

- southern blue flag (Iris virginica)

- wood nettle (Laportea canadensis)

- Michigan lily (Lilium michiganense)

- cardinal flower (Lobelia cardinalis)

- fringed loosestrife (Lysimachia ciliata)

- Virginia bluebells (Mertensia virginica)

- golden ragwort (Packera aurea)

- arrow-arum (Peltandra virginica)

- jumpseed (Persicaria virginiana)

- clearweed (Pilea pumila)

- Solomon-seal (Polygonatum biflorum)

- pickerel-weed (Pontederia cordata)

- swamp buttercup (Ranunculus hispidus)

- water dock (Rumex verticillatus)

- black snakeroots (Sanicula marilandica and S. odorata)

- lizard’s tail (Saururus cernuus)

- carrion flower (Smilax ecirrata)

- goldenrods (Solidago spp.)

- side-flowering aster (Symphyotrichum lateriflorum)

- skunk-cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus)

- wood-sage (Teucrium canadense)

- purple meadow-rue (Thalictrum dasycarpum)

- drooping trillium (Trillium flexipes)

- common trillium (Trillium grandiflorum)

- stinging nettle (Urtica dioica)

- violets (Viola spp.)

Ferns

- maidenhair fern (Adiantum pedatum)

- bulblet fern (Cystopteris bulbifera)

- wood ferns (Dryopteris spp.)

- ostrich fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris)

- sensitive fern (Onoclea sensibilis)

- royal fern (Osmunda regalis)

- New York fern (Thelypteris noveboracensis)

Fern Allies

- field horsetail (Equisetum arvense)

Woody Vines

- American bittersweet (Celastrus scandens)

- wild yam (Dioscorea villosa)

- moonseed (Menispermum canadense)

- Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia)

- poison-ivy (Toxicodendron radicans)

- riverbank grape (Vitis riparia)

Shrubs

- buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis)

- dogwoods (Cornus spp.)

- whorled loosestrife (Decodon verticillatus)

- wahoo (Euonymus atropurpurea)

- spicebush (Lindera benzoin)

- choke cherry (Prunus virginiana)

- sandbar willow (Salix exigua)

- bladdernut (Staphylea trifolia)

- black-haw (Viburnum prunifolium)

- prickly ash (Zanthoxylum americanum)

Trees

- box elder (Acer negundo)

- black maple (Acer nigrum)

- red maple (Acer rubrum)

- silver maple (Acer saccharinum)

- sugar maple (Acer saccharum)

- pawpaw (Asimina triloba)

- yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis)

- musclewood (Carpinus caroliniana)

- bitternut hickory (Carya cordiformis)

- shagbark hickory (Carya ovata)

- hackberry (Celtis occidentalis)

- redbud (Cercis canadensis)

- hawthorns (Crataegus spp.)

- beech (Fagus grandifolia)

- black ash (Fraxinus nigra)

- green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica)

- pumpkin ash (Fraxinus profunda)

- blue ash (Fraxinus quadrangulata)

- honey locust (Gleditsia triacanthos)

- Kentucky coffee-tree (Gymnocladus dioicus)

- butternut (Juglans cinerea)

- black walnut (Juglans nigra)

- red mulberry (Morus rubra)

- white pine (Pinus strobus)

- sycamore (Platanus occidentalis)

- cottonwood (Populus deltoides)

- swamp white oak (Quercus bicolor)

- bur oak (Quercus macrocarpa)

- red oak (Quercus rubra)

- peach-leaf willow (Salix amygdaloides)

- black willow (Salix nigra)

- northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis)

- basswood (Tilia americana)

- hemlock (Tsuga canadensis)

- American elm (Ulmus americana)

Noteworthy Animals

Large contiguous tracts of old-growth and mature floodplain forest provide important habitat for cavity nesters, species of detritus-based food webs, canopy-dwelling species, and interior forest obligates, including numerous neotropical migrants such as black-throated green warbler (Dendroica virens), scarlet tanager (Piranga olivacea), and ovenbird (Seiurus aurocapillus). Floodplain forests in Michigan support disproportionately large numbers of breeding bird species compared to upland landscapes and provide critical habitat for species closely associated with wetlands, including several rare species such as yellow-throated warbler (Dendroica dominica, state threatened), prothonotary warbler (Protonotaria citrea, state special concern), and Louisiana waterthrush (Seiurus motacilla, state special concern). Indiana bat (Myotis sodalis, federal/state endangered) establishes roosts and nurseries in standing snags within floodplain forests. Great blue heron (Ardea herodias) often construct rookeries within floodplain forests. Seasonally inundated portions of floodplains provide crucial habitat for reptiles and amphibians.

Rare Plants

- Arabis perstellata (rock cress, state threatened)

- Aristolochia serpentaria (Virginia snakeroot, state threatened)

- Aster furcatus (forked aster, state threatened)

- Camassia scilloides (wild-hyacinth, state threatened)

- Carex assiniboinensis (Assiniboia sedge, state threatened)

- Carex conjuncta (sedge, state threatened)

- Carex crus-corvi (raven’s-foot sedge, state threatened)

- Carex davisii (Davis’ sedge, state threatened)

- Carex decomposita (log sedge, state threatened)

- Carex frankii (Frank’s sedge, state special concern)

- Carex haydenii (Hayden's sedge, presumed extirpated from Michigan)

- Carex lupuliformis (false hop sedge, state threatened)

- Carex oligocarpa (eastern few-fruited sedge, state threatened)

- Carex squarrosa (sedge, state special concern)

- Carex trichocarpa (hairy-fruited sedge, state special concern)

- Carex typhina (cat-tail sedge, state threatened)

- Chasmanthium latifolium (wild oats, state threatened)

- Chelone obliqua (purple turtlehead, state endangered)

- Corydalis flavula (yellow fumewort, state threatened)

- Dasistoma macrophylla (mullein foxglove, state threatened)

- Dentaria maxima (large toothwort, state threatened)

- Diarrhena americana (beak grass, state threatened)

- Dryopteris celsa (log fern, state threatened)

- Euonymus atropurpurea (burning bush or wahoo, state special concern)

- Fraxinus profunda (pumpkin ash, state threatened)

- Galearis spectabilis (showy orchis, state threatened)

- Gentianella quinquefolia (stiff gentian, state threatened)

- Gymnocladus dioicus (Kentucky coffee-tree, state special concern)

- Hybanthus concolor (green violet, state special concern)

- Hydrastis canadensis (goldenseal, state threatened)

- Jeffersonia diphylla (twinleaf, state special concern)

- Justicia americana (water-willow, state threatened)

- Lithospermum latifolium (broad-leaved puccoon, state special concern)

- Lycopus virginicus (Virginia water horehound, state threatened)

- Mertensia virginica (Virginia bluebells, state threatened)

- Mikania scandens (climbing hempweed, presumed extirpated from Michigan)

- Monarda didyma (Oswego tea, presumed extirpated from Michigan)

- Morus rubra (red mulberry, state threatened)

- Panax quinquefolius (ginseng, state threatened)

- Plantago cordata (heart-leaved plantain, state endangered)

- Poa paludigena (bog bluegrass, state threatened)

- Polemonium reptans (Jacob’s ladder, state threatened)

- Pycnanthemum pilosum (hairy mountain mint, state threatened)

- Rudbeckia subtomentosa (sweet coneflower, presumed extirpated from Michigan)

- Ruellia strepens (smooth ruellia, state threatened)

- Scutellaria nervosa (skullcap, state threatened)

- Scutellaria ovata (heart-leaved skullcap, state threatened)

- Silphium perfoliatum (cup-plant, state threatened)

- Thalictrum venulosum var. confine (veiny meadow-rue, state special concern)

- Trillium nivale (snow trillium, state threatened)

- Trillium recurvatum (prairie trillium, state threatened)

- Trillium sessile (toadshade, state threatened)

- Valerianella chenopodiifolia (goosefoot corn-salad, state threatened)

- Valerianella umbilicata (corn-salad, state threatened)

- Viburnum prunifolium (black haw, state threatened)

- Wisteria frutescens (wisteria, state threatened)

Rare Animals

- Accipiter cooperii (Cooper’s hawk, state special concern)

- Ambystoma opacum (marbled salamander, state threatened)

- Ambystoma texanum (small-mouthed salamander, state endangered)

- Buteo lineatus (red-shouldered hawk, state threatened)

- Clonophis kirtlandii (Kirtland’s snake, state endangered)

- Dendroica cerulea (cerulean warbler, state special concern)

- Dendroica dominica (yellow-throated warbler, state threatened)

- Elaphe o. obsoleta (black rat snake, state special concern)

- Emydoidea blandingii (Blanding’s turtle, state special concern)

- Glyptemys insculpta (wood turtle, state special concern)

- Myotis sodalis (Indiana bat, federal/state endangered)

- Nerodia erythrogaster neglecta (copperbelly watersnake, federal threatened and state endangered)

- Protonotaria citrea (prothonotary warbler, state special concern)

- Seiurus motacilla (Louisiana waterthrush, state special concern)

- Sistrurus c. catenatus (eastern massasauga, federal candidate species and state special concern)

- Tachopteryx thoreyi (grey petaltail, state special concern)

- Terrapene c. carolina (eastern box turtle, state special concern)

- Wilsonia citrina (hooded warbler, state special concern)

Rare Aquatic Animals

- Acipenser fulvescens (lake sturgeon, state threatened)

- Alasmidonta marginata (elktoe, state special concern)

- Ammocrypta pellucida (eastern sand darter, state threatened)

- Anguispira kochi (banded globe, state special concern)

- Cyclonaias tuberculata (purple wartyback, state special concern)

- Discus patulus (domed disc, state special concern)

- Epioblasma torulosa rangiana (northern riffleshell, state endangered)

- Epioblasma triquetra (snuffbox, state endangered)

- Lampsilis fasciola (wavy-rayed lampmussel, state threatened)

- Lepisosteus oculatus (spotted gar, state special concern)

- Moxostoma carinatum (river redhorse, state threatened)

- Noturus stigmosus (northern madtorn, state endangered)

- Obovaria olivaria (hickorynut, state special concern)

- Obovaria subrotunda (round hickorynut, state endangered)

- Opsopoeodus emiliae (pugnose minnow, state endangered)

- Percina copelandi (channel darter, state endangered)

- Percina shumardi (river darter, state endangered)

- Pleurobema clava (northern clubshell, state endangered)

- Pleurobema coccineum (round pigtoe, state special concern)

- Pomatiopsis cincinnatiensis (brown walker, state special concern)

- Simpsonaias ambigua (salamander mussel, state endangered)

- Toxolasma lividus (purple lilliput, state endangered)

- Venustaconcha ellipsiformis (ellipse, state special concern)

- Villosa fabalis (rayed bean, state endangered)

- Villosa iris (rainbow, state special concern)

Biodiversity Management Considerations

Successful conservation and management of floodplain forests can contribute significantly to regional biodiversity because these systems possess an unusually high diversity of plant and animal species, vegetation types, and ecological processes. By providing necessary hibernacula, breeding sites, foraging areas, and travel corridors, floodplain forests often support a high diversity of birds, herptiles, and mammals. Wider and more contiguous riparian systems support high levels of native plant species diversity compared to narrow, fragmented riparian systems. Riparian corridors may harbor twice the number of species than that found in adjacent upland areas.

Conservation and management of floodplain forests require an ecosystem management perspective because of the complex longitudinal, lateral, and vertical dimensions of river systems. It is crucial to maintain the connectivity and longitudinal environmental gradients from headwater streams to the broad floodplains located downstream. The natural spatial and temporal patterns of stream flow rates, water levels, and run-off patterns must be maintained or reestablished, where feasible, because these hydrologic processes create the diverse structure that characterizes floodplain forests. Maintaining vegetated buffers in the uplands bordering floodplain forests will help improve stream water quality. Restoration of channel morphology may be important in areas where stream channelization, channel constriction, and dams have altered water delivery and geomorphology. Conservation and restoration of fragmented floodplain forests also requires active long-term management to maintain deer at low densities.

Floodplain forests are highly susceptible to invasions by non-native species. Because of their linear shape and location between aquatic and terrestrial environments, floodplain forests have a high ratio of edge to interior habitat that may facilitate the movement of opportunistic species. Rivers and streams provide a route of transport that facilitates the spread of species across the landscape. Floodplain forests are highly and frequently disturbed systems that contain extensive areas of exposed mineral soil with high nutrient availability, characteristics that facilitate invasion by non-native species. Preemptive measures to minimize impacts of invasive species include maintaining mature floodplain forest, minimizing and eliminating trails and roads through floodplains, and buffering riparian areas with mature, continuous uplands. Once invasive species become established, control (through manual removal) becomes costly and intensive. Thus, monitoring and control efforts to detect and remove invasive species are critical to the long-term viability of floodplain forest. Some of the many invasive species that threaten the diversity and community structure of floodplains forests include garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata), Dame’s rocket (Hesperis matronalis), moneywort (Lysimachia nummularia), ground ivy (Glechoma hederacea), purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), narrow-leaved cat-tail (Typha angustifolia), hybrid cat-tail (Typha xglauca), reed (Phragmites australis subsp. australis), reed canary grass (Phalaris arundinacea), European marsh thistle (Cirsium palustre), glossy buckthorn (Frangula alnus), common buckthorn (R. cathartica), Eurasian honeysuckles (Lonicera morrowii, L. japonica, L. maackii, L. tatarica, L. xbella, and L. xylosteum), Oriental bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus), Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii), multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora), autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata), common privet (Ligustrum vulgare), white mulberry (Morus alba), and Norway maple (Acer platanoides). In addition to non-native plant species, non-native pathogens and insects have profoundly altered floodplain forests (e.g., Dutch elm disease and the emerald ash borer).

Throughout North America, almost all large rivers and their floodplains are subject to multiple hydrologic alterations, such as human-made levees, impoundments, channelization, dams, and changes in land use. By changing the flow of water, such hydrologic alterations interrupt flood pulses, which are critical in the dynamics of seed dispersal, plant establishment, nutrient cycling, channel scouring, sediment deposition, and the maintenance of species richness. Changes in land cover surrounding the floodplain have also altered species composition and structure within floodplain forests. Agricultural land cover in the adjacent uplands often leads to high-nutrient runoff entering the floodplain and stream, which lowers stream water quality. The abundance of impervious surface in urban landscapes often results in a flashy discharge into nearby rivers and degrades water quality.

Variation

Shifts in species composition occur gradually along a gradient from south to north, and to a lesser extent from lake-moderated areas along the coast to the interior of the state. Species richness is greatest in floodplains of the southern Lower Peninsula, where a number of species reach their northern extent. Conifers are typically absent from floodplains in the southern Lower Peninsula, though they may occur in groundwater seepages and meander-scar swamps, where organic soils accumulate. In northern Michigan, conifers often dominate backswamps, meander-scar swamps, and groundwater seepages. Compared to southern Michigan floodplains, grasses and sedges account for a larger portion of the ground flora in floodplains of northern Michigan.

Floodplains within outwash plains and lakeplains are typically broader and more continuous than floodplains in morainal landscapes. When a river flows through a broad outwash plain or a lakeplain, the low topographic gradient and high sand content of the bank promotes the development of broad first bottoms, where extensive channel migration leads to the formation of a variety of fluvial landforms, including natural levees, meander scrolls, oxbow lakes, backswamps, and meander-scar swamps. In contrast, when a river flows through a morainal landscape, the higher topographic relief, steeper slope gradients, and finer textured soil restrict channel migration, resulting in narrow floodplains that are often dissected by higher terraces. The frequency and duration of flooding are reduced, and the ridge and swale topography that characterizes first bottoms within outwash plains and lakeplains is usually lacking.

Similar Natural Communities

Hardwood-conifer swamp, mesic southern forest, mesic northern forest, northern hardwood swamp, and southern hardwood swamp.

Places to Visit

- Aman Park, City of Grand Rapids, Ottawa Co.

- Big Daily Bayou, Allegan State Game Area, Allegan State Game Area, Allegan Co.

- Black River Floodplain Forest, Port Huron State Game Area, St. Clair Co.

- Haggerty Road Floodplain, Lower Huron Metropark, Wayne Co.

- Manistee River Floodplain, Manistee River State Game Area, Manistee Co.

- Maple River Floodplain, Maple River State Game Area, Clinton Co.

- Muskegon River, Gladwin State Forest Management Unit, Clare Co.

- Sturgeon River, Hiawatha National Forest, Delta Co.

- Warren Woods, Warren Woods State Park, Berrien Co.

- White River, Manistee National Forest, Oceana Co.

Relevant Literature

- Baker, M.E., and B.V. Barnes. 1998. Landscape ecosystem diversity of river floodplains in northwestern Lower Michigan, U.S.A. Canadian Journal of Forestry Research 28: 1405-1418.

- Gergel, S.E., M.D. Dixon, and M.G. Turner. 2002. Consequences of human-altered floods: Levees, floods, and floodplain forests along the Wisconsin River. Ecological Applications 12: 1755- 1770.

- Goforth, R.R., D. Stagliano, Y.M. Lee, J.G. Cohen, and M.R. Penskar. 2002. Biodiversity analysis of selected riparian ecosystems within a fragmented landscape. Michigan Natural Features Inventory. Lansing, MI. 126 pp.

- Gregory, S.V., F.J. Swanson, W.A. McKee, and K.W. Cummins. 1991. An ecosystem perspective of riparian zones. Bioscience 41: 540-551.

- Inman, R.L., H.H. Prine, and D.B. Hayes. 2002. Avian communities in forested riparian wetlands of southern Michigan, USA. Wetlands 22: 647-660.

- Malanson, G.P. 1993. Riparian landscapes. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 296 pp.

- Naiman, R.J., H. Décamps, and M. Pollock. 1993. The role of riparian corridors in maintaining regional biodiversity. Ecological Applications 3: 209-212.

- Planty-Tabacchi, A., E. Tabacchi, R.J. Naiman, C. Deferrari, and H. Décamps. 1996. Invasibility of species-rich communities in riparian zones. Conservation Biology 10: 598-607.

- Sparks, R. 1995. Need for ecosystem management of large rivers and their floodplains. Bioscience 45(3): 168-182.

- Tepley, A.J., J.G. Cohen, and L. Huberty. 2004. Natural community abstract for floodplain forest. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI.14 pp.

- Verry, E.S., and C.A. Dolloff. 2000. The challenge of managing for healthy riparian areas. Pp. 1-20 in Riparian management in forests of the continental eastern United States, ed. E.S. Verry, J.W. Hornbeck, and C.A. Dollof. Lewis Publishers, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. 432 pp.

- Verry, E.S., J.W. Hornbeck, and C.A. Dolloff, eds. 2000. Riparian management in forests of the continental eastern United States. Lewis Publishers, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. 432 pp.

- Ward, J.V. 1998. Riverine landscapes: Biodiversity patterns, disturbance regimes, and aquatic conservation. Biological Conservation 83: 269-278.

For a full list of references used to create this description, please refer to the natural community abstract for Floodplain Forest.

More Information

Citation

Cohen, J.G., M.A. Kost, B.S. Slaughter, D.A. Albert, J.M. Lincoln, A.P. Kortenhoven, C.M. Wilton, H.D. Enander, and K.M. Korroch. 2020. Michigan Natural Community Classification [web application]. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Michigan State University Extension, Lansing, Michigan. Available https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/communities/classification. (Accessed: April 25, 2024).

Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2007-21, Lansing, MI.